Etruscan civilization

Its culture flourished in three confederacies of cities: that of Etruria (Tuscany, Latium and Umbria), that of the Po Valley with the eastern Alps, and that of Campania.

[18][25] The Etruscans developed a system of writing derived from the Euboean alphabet, which was used in the Magna Graecia (coastal areas located in Southern Italy).

The Etruscan language remains only partly understood, making modern understanding of their society and culture heavily dependent on much later and generally disapproving Roman and Greek sources.

The term Tusci is thought by linguists to have been the Umbrian word for "Etruscan", based on an inscription on an ancient bronze tablet from a nearby region.

[57] The discovery of these inscriptions in modern times has led to the suggestion of a "Tyrrhenian language group" comprising Etruscan, Lemnian, and the Raetic spoken in the Alps.

And I do not believe, either, that the Tyrrhenians were a colony of the Lydians; for they do not use the same language as the latter, nor can it be alleged that, though they no longer speak a similar tongue, they still retain some other indications of their mother country.

[59] The Alpine tribes have also, no doubt, the same origin (of the Etruscans), especially the Raetians; who have been rendered so savage by the very nature of the country as to retain nothing of their ancient character save the sound of their speech, and even that is corrupted.The first-century historian Pliny the Elder also put the Etruscans in the context of the Rhaetian people to the north, and wrote in his Natural History (AD 79):[60] Adjoining these the (Alpine) Noricans are the Raeti and Vindelici.

The Raeti are believed to be people of Tuscan race driven out by the Gauls, their leader was named Raetus.The question of the origins of the Etruscans has long been a subject of interest and debate among historians.

[62] In 2000, the etruscologist Dominique Briquel explained in detail why he believes that ancient Greek narratives on Etruscan origins should not even count as historical documents.

[67] The most marked and radical change that has been archaeologically attested in the area is the adoption, starting in about the 12th century BC, of the funeral rite of incineration in terracotta urns, which is a Continental European practice, derived from the Urnfield culture; there is nothing about it that suggests an ethnic contribution from Asia Minor or the Near East.

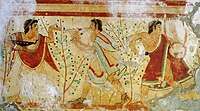

[71] The facial features (the profile, almond-shaped eyes, large nose) in the frescoes and sculptures, and the depiction of reddish-brown men and light-skinned women, influenced by archaic Greek art, followed the artistic traditions from the Eastern Mediterranean, that had spread even among the Greeks themselves, and to a lesser extent also to other several civilizations in the central and western Mediterranean up to the Iberian Peninsula.

[77] An archeogenetic study focusing on the question of Etruscan origins was published in September 2021 in the journal Science Advances and analyzed the autosomal DNA and the uniparental markers (Y-DNA and mtDNA) of 48 Iron Age individuals from Tuscany and Lazio, spanning from 800 to 1 BC, and concluding that the Etruscans were autochthonous (locally indigenous), and they had a genetic profile similar to their Latin neighbors.

[83] A couple of mitochondrial DNA studies, published in 2013 in the journals PLOS One and American Journal of Physical Anthropology, based on Etruscan samples from Tuscany and Latium, concluded that the Etruscans were an indigenous population, showing that Etruscan mtDNA appears to fall very close to a Neolithic population from Central Europe (Germany, Austria, Hungary) and to other Tuscan populations, strongly suggesting that the Etruscan civilization developed locally from the Villanovan culture, as already supported by archaeological evidence and anthropological research,[17][84] and that genetic links between Tuscany and western Anatolia date back to at least 5,000 years ago during the Neolithic and the "most likely separation time between Tuscany and Western Anatolia falls around 7,600 years ago", at the time of the migrations of Early European Farmers (EEF) from Anatolia to Europe in the early Neolithic.

[75][76] In his 2021 book, A Short History of Humanity, German geneticist Johannes Krause, co-director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Jena, concludes that it is likely that the Etruscan language (as well as Basque, Paleo-Sardinian, and Minoan) "developed on the continent in the course of the Neolithic Revolution".

In the last Villanovan phase, called the recent phase (about 770–730 BC), the Etruscans established relations of a certain consistency with the first Greek immigrants in southern Italy (in Pithecusa and then in Cuma), so much so as to initially absorb techniques and figurative models and soon more properly cultural models, with the introduction, for example, of writing, of a new way of banqueting, of a heroic funerary ideology, that is, a new aristocratic way of life, such as to profoundly change the physiognomy of Etruscan society.

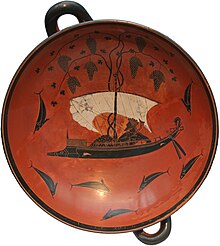

The mining and commerce of metal, especially copper and iron, led to an enrichment of the Etruscans and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian peninsula and the western Mediterranean Sea.

Here, their interests collided with those of the Greeks, especially in the sixth century BC, when Phocaeans of Italy founded colonies along the coast of Sardinia, Spain and Corsica.

Though the battle had no clear winner, Carthage managed to expand its sphere of influence at the expense of the Greeks, and Etruria saw itself relegated to the northern Tyrrhenian Sea with full ownership of Corsica.

Although there is no consensus on which cities were in the league, the following list may be close to the mark: Arretium, Caisra, Clevsin, Curtun, Perusna, Pupluna, Veii, Tarchna, Vetluna, Volterra, Velzna, and Velch.

According to Livy, the twelve city-states met once a year at the Fanum Voltumnae at Volsinii, where a leader was chosen to represent the league.

[99] There were two other Etruscan leagues ("Lega dei popoli"): that of Campania, the main city of which was Capua, and the Po Valley city-states in northern Italy, which included Bologna, Spina and Adria.

Like many ancient societies, the Etruscans conducted campaigns during summer months, raiding neighboring areas, attempting to gain territory and combating piracy as a means of acquiring valuable resources, such as land, prestige, goods, and slaves.

Prisoners could also potentially be sacrificed on tombs to honor fallen leaders of Etruscan society, not unlike the sacrifices made by Achilles for Patrocles.

They were entirely assimilated by Italic, Celtic, or Roman ethnic groups, but the names survive from inscriptions and their ruins are of aesthetic and historic interest in most of the cities of central Italy.

[109] Vite maritata is a viticulture technique exploiting companion planting named after the Maremma region of Italy which may be relevant to climate change.

[112][113] Ruling over this pantheon of lesser deities were higher ones that seem to reflect the Indo-European system: Tin or Tinia, the sky, Uni his wife (Juno), and Cel, the earth goddess.

Most surviving Etruscan art comes from tombs, including all the fresco wall-paintings, a minority of which show scenes of feasting and some narrative mythological subjects.

Etruscan temples were heavily decorated with colorfully painted terracotta antefixes and other fittings, which survive in large numbers where the wooden superstructure has vanished.

Little is known of it and even what is known of their language is due to the repetition of the same few words in the many inscriptions found (by way of the modern epitaphs) contrasted in bilingual or trilingual texts with Latin and Punic.

[126] One of the oldest Etruscan written documents is found on the tablet of Marsiliana d’Albegna from the hinterland of Vulci, which is now kept in the National Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Etruscan: Tular Rasnal

English: Boundary of the People