Caciquism

[6] Brought back by Christopher Columbus upon his return from his first voyage to America [es] in 1492,[8][9] the conquistadors utilized the term and expanded its usage to include the Central American setting and other indigenous groups they encountered,[6][7] even up to the absolute rulers of the pre-Columbian empires.

[13] At least since the eighteenth century, the term has had a broader meaning of "a dominating individual who instills fear and holds influence in a locality," with a negative connotation within the peninsular context.

Additionally, the definition explains that the term is used metaphorically to refer to the first leader of a Pueblo or Republic who wields more power and commands more respect by being feared and obeyed by those beneath them.

Consequently, the term "cacique" has evolved into a timeless and universal concept, applicable to any societal group and context in reference to power dynamics that involve patronage, clientelism, paternalism, dependence, favors, punishments, thanks, and curses among unequal individuals.

"[21] With the local population under his control and votes not taking place via secret ballot -a phenomenon not unique to Spain- the cacique could easily determine the outcome of elections.

[25] Some scholars argue that the political system during Isabella II's reign was an extreme example of oligarchy, as evidenced by censal suffrage laws that restricted the vote only to large and, occasionally, medium-sized landowners.

The political system in Isabelline Spain was largely controlled by caciques, as evidenced by the fact that the party that called the majority of the twenty-two elections held during this period was consistently victorious.

[27] Furthermore, clientelist political relationships had become well-established in the mid-nineteenth century and persisted throughout the democratic sexennium without being eliminated, as no government during this time was voted out of power.

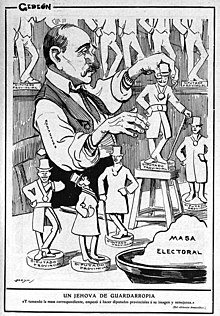

[33] In 1901, the Ateneo de Madrid conducted a survey and debate focused on Spain's socio-political system, with the participation of around sixty politicians and intellectuals.

Joaquín Costa, a regenerationist, summarized the discussion in his work titled Oligarchy and Caciquism as Representing the Current Form of Government in Spain [fr].

More than a century later, Carmelo Romero Salvador notes that Costa's two-word description, which has become the title of historical literature and manuals, remains the most commonly used term to depict the Restorationist period.

The "politician" in Madrid; the "cacique" in each comarca; the civil governor in the capital of each province as a link between the one and the other, constitute the three key pieces in the actual functioning of the system.

[35] A comparable interpretation of Costa's analysis is shared by Joaquín Romero Maura, cited by Feliciano Montero [fr], who also agrees that it was the most commonly used explanation for the phenomenon of caciquism during the Restoration era in Spain.

According to Romero Maura, Costa and those who share his interpretation view caciquismo as a political manifestation of the economic dominance of landed and financial elites.

This phenomenon is facilitated by a disengaged electorate, which is a result of the low level of economic development and social integration in various regions of the country, including factors such as poor communication, a closed economy, and high illiteracy rates.

[36] In the early 1970s, a new perspective on caciquism emerged among historians, including Joaquín Romero Maura, José Varela Ortega, and Javier Tusell.

[39] The central role of a cacique, who typically lacks an official position and may not be a powerful figure, is to act as an intermediary between the Administration and their extensive clientele from all social strata.

[41] To illustrate, Asturias boasted a truly deluxe network of roads during the early 20th century thanks to cacique Alejandro Pidal y Mon and his son Pedro.

He can create or eliminate jobs, open or close businesses, manipulate local justice and administration,[43] obtain exemptions from military obligations, misappropriate taxes to benefit local politicians, allow discreet purchases of essential goods without payment of consumos,[44] assist with administrative procedures, facilitate the creation of new infrastructure like roads or schools,[40] and lend his own money.

"Feliciano Montero characterizes the cacique as the intermediary between the central administration and the citizens, indicating that the entity yields influence beyond the electoral period, despite this being the most scandalous time.

Caciquism primarily represents the manifestation and logical expression of a social and political structure that persistently displays in the daily interpersonal interactions through patron-client relationships and political-administrative connections.

[49] During the Restoration era, a judge described caciquism as "the personal regime exercised in the villages [pueblos] by twisting or corrupting the proper functions of the State through political influence, in order to subordinate them to the selfish interests of certain individuals or groups.

Indeed, within the same political party that controlled the Council of Ministers, various factions routinely coexisted, each represented by leaders of different clienteles who claimed a certain number of parliamentary seats based on their influence.

[1][54] Following the encasillado event in Madrid, discussions continued on a local level through the designated representative of central power in each province, the civil governor.

The powerful local political figures, known as caciques, exerted significant influence over key positions such as town halls and courts.

[59][60] At times, there was a possibility that public opinion could shatter the oligarchic political circle, such as the instances when universal male suffrage was implemented in 1890, during the colonial crisis in 1898, or towards the end of the Restoration when the turno parties were disbanding.

The public's acceptance of Primo de Rivera's coup d'état in 1923 can be partially attributed to the sense of powerlessness felt by those seeking significant political change.

Meanwhile, powerful traditional entities in the agrarian sphere started organizing themselves into political parties capable of competing under the new circumstances, in order to defend their interests.

According to British historian Raymond Carr, caciquism is a result of formally democratic institutions being imposed on an underdeveloped economy, an "anemic society" as described by José Ortega y Gasset.

[62] As per the analysis by historian Pamela Radcliff, caciquism emerged as a modern mechanism of the liberal revolution that articulated the new state within the specific local/central dynamics of nineteenth-century Spain.