Republicanism

The word "republic" derives from the Latin noun-phrase res publica (public thing), which referred to the system of government that emerged in the 6th century BCE following the expulsion of the kings from Rome by Lucius Junius Brutus and Collatinus.

[10] A number of Ancient Greek city-states such as Athens and Sparta have been classified as "classical republics", because they featured extensive participation by the citizens in legislation and political decision-making.

Both Livy, a Roman historian, and Plutarch, who is noted for his biographies and moral essays, described how Rome had developed its legislation, notably the transition from a kingdom to a republic, by following the example of the Greeks.

The Greek historian Polybius, writing in the mid-2nd century BCE, emphasized (in Book 6) the role played by the Roman Republic as an institutional form in the dramatic rise of Rome's hegemony over the Mediterranean.

While in his theoretical works he defended monarchy, or at least a mixed monarchy/oligarchy, in his own political life, he generally opposed men, like Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, and Octavian, who were trying to realise such ideals.

In Tacitus' opinion, the trend away from a true republic was irreversible only when Tiberius established power, shortly after Augustus' death in 14 CE (much later than most historians place the start of the Imperial form of government in Rome).

While Niccolò Machiavelli's Discourses on Livy is the period's key work on republics, he also wrote the treatise The Prince, which is better remembered and more widely read, on how best to run a monarchy.

Although perhaps an unlikely place to act as a laboratory for such political experiments, Corsica combined a number of factors that made it unique: a tradition of village democracy; varied cultural influences from the Italian city-states, Spanish empire and Kingdom of France which left it open to the ideas of the Italian Renaissance, Spanish humanism and French Enlightenment; and a geo-political position between these three competing powers which led to frequent power vacuums in which new regimes could be set up, testing out the fashionable new ideas of the age.

During the initial period (1729–36) these merely sought to restore the control of the Spanish Empire; when this proved impossible, an independent Kingdom of Corsica (1736–40) was proclaimed, following the Enlightenment ideal of a written constitutional monarchy.

But the perception grew that the monarchy had colluded with the invading power, a more radical group of reformers led by the Pasquale Paoli pushed for political overhaul, in the form of a constitutional and parliamentary republic inspired by the popular ideas of the Enlightenment.

But the episode resonated across Europe as an early example of Enlightened constitutional republicanism, with many of the most prominent political commentators of the day recognising it to be an experiment in a new type of popular and democratic government.

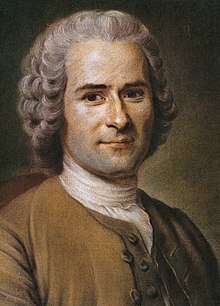

Its influence was particularly notable among the French Enlightenment philosophers: Rousseau's famous work On the Social Contract (1762: chapter 10, book II) declared, in its discussion on the conditions necessary for a functional popular sovereignty, that "There is still one European country capable of making its own laws: the island of Corsica.

Oliver Cromwell set up a Christian republic called the Commonwealth of England (1649–1660) which he ruled after the overthrow of King Charles I. James Harrington was then a leading philosopher of republicanism.

In his epic poem Paradise Lost, for instance, Milton uses Satan's fall to suggest that unfit monarchs should be brought to justice, and that such issues extend beyond the constraints of one nation.

[26] As Christopher N. Warren argues, Milton offers "a language to critique imperialism, to question the legitimacy of dictators, to defend free international discourse, to fight unjust property relations, and to forge new political bonds across national lines.

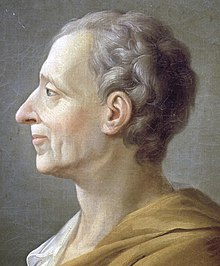

[34] Pocock explained the intellectual sources in America:[35] The Whig canon and the neo-Harringtonians, John Milton, James Harrington and Sidney, Trenchard, Gordon and Bolingbroke, together with the Greek, Roman, and Renaissance masters of the tradition as far as Montesquieu, formed the authoritative literature of this culture; and its values and concepts were those with which we have grown familiar: a civic and patriot ideal in which the personality was founded in property, perfected in citizenship but perpetually threatened by corruption; government figuring paradoxically as the principal source of corruption and operating through such means as patronage, faction, standing armies (opposed to the ideal of the militia), established churches (opposed to the Puritan and deist modes of American religion) and the promotion of a monied interest – though the formulation of this last concept was somewhat hindered by the keen desire for readily available paper credit common in colonies of settlement.

On the first Russell, Neilson, Simms, McCracken and one or two more of us, on the summit of McArt's fort, took a solemn obligation...never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country and asserted her independence.

They were on the left of the political spectrum, along Jacobin lines, and defended broad reforms such as the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic, federalism, the extinction of the Moderating Power, the end of life tenure in the Senate, the separation between Church and State, relative social equality, the extension of political and civil rights to all free segments of society, including women, the staunch opposition to slavery, displaying a nationalist, xenophobic and anti-Portuguese discourse.

[45] In 1870 a group of radical liberals, convinced of the impossibility of achieving their desired reforms within the Brazilian monarchical system, met and founded the Republican Party.

The republican movement was strongest in the Court and in São Paulo, but other smaller foci also emerged in Minas Gerais, Pará, Pernambuco and Rio Grande do Sul.

He was sentenced to death and shot in 1870 for having favored an insurrectional attempt against the Savoy monarchy and is therefore considered the first martyr of the modern Italian Republic[48][49] and a symbol of republican ideals in Italy.

[62][63] As the United States constitution prohibits granting titles of nobility, republicanism in this context does not refer to a political movement to abolish such a social class, as it does in countries such as the UK, Australia, and the Netherlands.

Many key political figures in the region identified as republicans, including Simón Bolívar, José María Samper, Francisco Bilbao, and Juan Egaña.

Another "significant incarnation" of republicanism broke out in the late 19th century when Queen Victoria went into mourning and largely disappeared from public view after the death of her husband, Prince Albert.

More recently, in the early 21st century, increasing dissatisfaction with the House of Windsor, especially after the death of Elizabeth II in 2022, has led to public support for the monarchy reaching historical lows.

While these movements have shared the objective of establishing a republic, during these three centuries there have surged distinct schools of thought on the form republicans would want to give to the Spanish State: unitary or federal.

[30] Republicans, in these two examples, tended to reject inherited elites and aristocracies, but left open two questions: whether a republic, to restrain unchecked majority rule, should have an unelected upper chamber—perhaps with members appointed as meritorious experts—and whether it should have a constitutional monarch.

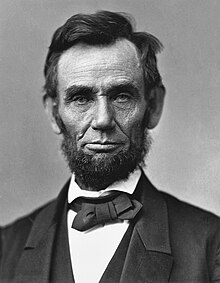

"[102] Professors Richard Ellis of Willamette University and Michael Nelson of Rhodes College argue that much constitutional thought, from Madison to Lincoln and beyond, has focused on "the problem of majority tyranny."

They conclude, "The principles of republican government embedded in the Constitution represent an effort by the framers to ensure that the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness would not be trampled by majorities.

Often the monarchy was abolished along with the aristocratic system, whether or not they were replaced with democratic institutions (such as in France, China, Iran, Russia, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Greece, Turkey and Egypt).