Cadejo

They usually appear in the form of a large, shaggy dog (potentially as big as a cow) with burning red eyes and goats hooves, although, in some areas, they have more rough characteristics.

Some Guatemalan and Salvadoran folklore also tells of a cadejo that protects drunk people against anyone who tries to rob or hurt them.

There is a fairly large member of the weasel family, the tayra, which is called a cadejo and is cited as a possible source of the legend.

They mysteriously appear at night and lovingly protect the villagers who live on the slopes of the volcanoes from danger.

There are three types of black cadejos: The first is the devil himself in the form of a large, wounded dog with hoofed feet that are bound with red-hot chains.

Unlike the regular black cadejo, it is not likely to pursue and attack a passing person, as it is a scout - the eyes of evil.

It is a mortal hybrid and can (with difficulty) be killed by a strong man (bearing in mind that most men in those regions only carry a machete for protection).

Once dead, it will completely rot in a matter of seconds, leaving behind a stain of evil, on which grass and moss will never grow again.

A fairly popular version of the legend in El Salvador talks about two brothers who walk into the house of a black magician.

Once he finds out that the little bit of food he had is missing and that there is not enough wood for his fire, he puts a curse on the road that leads to the boys' village.

In the early 20th century, Juan Carlos was a guardian who lived in a thatched house near Los Arcos, in the country fields near La Aurora in Guatemala.

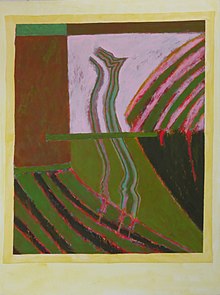

The cadejo is a primary motif in the paintings of Guatemalan-born artist Carlos Loarca, who was born in 1937.

As a child, Loarca was told the legend and believed that the cadejo protected his father, as he always came home unscathed from the cantina.

The bilingual Spanish-English edition was translated by Stacey Ross and illustrated by Elly Simmons.