Cadet scandal

In 1942, Ballvé Piñero and his group of friends, including Adolfo José Goodwin, Ernesto Brilla, Romeo Spinetto and Sonia—the only woman—among others, started to pick up cadets off the streets for their private parties, with some even developing romantic relationships.

The news of the incident made a great impact on the society and yellow press of Buenos Aires, to the extent that lists of prominent alleged homosexuals were disseminated anonymously among the population, and cadets were regularly ridiculed in the streets.

The legacy of the scandal has been compared to that of Oscar Wilde's trial in the United Kingdom, the Dance of the Forty-One in Mexico and the Eulenburg affair in Germany, and is considered a turning point in the country's history of homophobia.

In 2019, playwright Gonzalo Demaría became the first person to have access to the case files—the contents of which had been a great source of speculation for Argentine LGBT historians such as Juan José Sebreli, Jorge Salessi and Osvaldo Bazán—and published his research in the first book focused on the scandal the following year.

[1][2] In 1930, the first coup d'état in Argentine 20th century history established the military regime of nationalist General José Félix Uriburu, which ended the democratic rule of President Hipólito Yrigoyen.

[7] The following year, there was a homosexuality scandal in the Argentine Army itself,[7] when Captain Arturo Macedo was killed by a gunshot perpetrated by Major Juan Comas, who later tried to commit suicide in an episode regarded at the time as a "crime of passion" that was little concealed by the press.

[16] The only individuals at the disposal of de Veyga and Ingenieros were prisoners of lunfardo origin (i.e. the underclass), thus creating a cliché that linked homosexuality to criminal life and parodic imitations of women.

[35] During the government of Juan Manuel de Rosas—who ruled Buenos Aires in the 1830s and 1840s—his mother's German great-grandfather, Klaus Stegmann, amassed a great fortune, with an estate that had thousands of fertile hectares.

[43] As part of this new life, Ballvé Piñero started renting a bachelor pad in the city center,[44] and later, following the death of his grandfather, moved altogether to an apartment on 1381 Junín street, in Recoleta.

[47] To medical experts from 1941, Ballvé Piñero explained his modus operandi for picking up young men consisted of driving at low speed along Corrientes avenue, between Alem and Esmeralda streets, at two or three in the morning until he found someone that drew his attention.

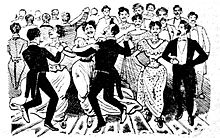

[48] The established discourse maintains that crowded orgies and sex parties were held in Ballvé Piñero's department,[49] which has been dismissed by more recent research as an "urban legend", describing them instead as more or less improvised meetings with dances between several young men, drinks and political discussions.

[50][51] Nevertheless, this type of parties did take place according to various testimonies, including one cross dressing ball—only attended by locas—and another held around 1937 by the so-called "Barón Hell"—German spy Georg Helmut Lenk—in aristocrat Pepo Dose's palace on Avenida Alvear.

[53] Ballvé Piñero's close group of friends included Adolfo José Goodwin, Ernesto Brilla, Romeo Spinetto and young model Sonia (pseudonym of Blanca Nieve Abratte), the only woman involved.

[71] A second raid on Ballvé Piñero's department took place on September 3;[70] by then, a complaint before the civil justice had just been filed by three upper-class men—[72] Fernando Cullen, Andrés Bacigalupo Rosende and Franklin Dellepiano Rawson—who formalized a lawsuit for corruption of minors, taken by prosecutor Luciano Landaburu and investigating judge Narciso Ocampo Alvear.

[81] As a result, the Ministry of War (Spanish: Ministerio de Guerra) issued a resolution that forced them to publicly wear the uniform despite any incident,[81] and to "not tolerate any joke that would injure military honor.

"[30] On the night of September 26, a large street fighting occurred in the city center between cadets and civilians and, the following week, they came out in small groups ready to attack anyone who insulted them, badly injuring a young man.

[84] Researchers Karina Inés Ramacciotti and Adriana María Valobra note that the scandal "had a symbolic impact, accentuating a past homophobia and questioning the effectiveness of [the Social Prophylaxis Law].

[84][85] News of the scandal broke out in the press on October 30 and 31, 1942,[49] and divided it among those who did not dare to publish more than a short paragraph full of euphemisms and, on the other hand, sensationalist, yellow journalism illustrated with fictitious photos.

[86] Several writers consider that the cadet scandal served as one of the justifications for the military coup d'état that took place nine months later on June 4, 1943, which had the self-proclaimed objective of "moral sanitation" and promoted the idea of a "corrupt oligarchy".

"[30] Acha and Ben point out that even though the criticism of the "corruption" of politicians and the defense of morality are mentioned in GOU's documents, the "sexual invert" accusation was only used following the coup, within the internal struggles of the military sectors, in which the group sought to displace an official from the Ministry of Justice and Public Instruction (Spanish: Ministerio de Justicia e Instrucción Pública).

[97] Many of the men mentioned in the prosecution ended up with preventive detention, including writer Carlos Zubizarreta, Miguel Ángel Bres Miranda, Raúl Padilla and choreographer Rafael García.

[112] The repression of homosexuality increased with the new military regime installed on June 4, 1943, as part of the censorship and control that it exercised over radio broadcasting, periodicals, theater, trade unions and political activity.

[30] Although during the rest of 1942 homosexual activities were more closely watched than usual as a result of the scandal, it was the new regime who carried out the first anti-homosexual operation of great repercussion: the deportation of Spanish singer and actor Miguel de Molina, who had settled in Buenos Aires in 1942.

[114] In the port of Buenos Aires, de Molina was farewelled by renowned actresses Iris Marga, Gloria Guzmán and Sofía Bozán, although no men attended due to the stigma of homosexuality.

"[115] In 1944—during the de facto government of Pedro Pablo Ramírez—an anti-homosexual science book written by doctor J. Gómez Nerea became a bestseller, which described Argentine homosexuality in the following terms: It is known that in the literary and artistic environment of Buenos Aires there is a very high percentage of inverts.

Actors, poets, renowned politicians [and] magistrates practice the terrible vice, and although society has pointed the finger of stigmatization on them, nothing can be done against them... (...) ... the percentage of sexual inversion among us reaches extremely high figures, perhaps astronomical ones.

"[122][123] According to Omar Acha and Pablo Ben, the definition of gay men as a singular group was established during Perón's first government, even though the concept of homosexuality that characterized the time was different from the one that prevails today.

[68] After drawing a connection between the cadet scandal and these last two, Adrián Melo wrote in Soy magazine in 2019: "Each country has a founding fact and a landmark that represents a turning point in the history of homophobia, which condenses prejudices and scientific, medical and legal knowledge about homosexuality and legitimizes repression.

"[68] However, Melo also pointed out in another publication that, while the Dance of the Forty-One has been reclaimed by the Mexican LGBT community, the cadet scandal has been historically silenced in Argentina—except for the pioneering researches of Juan José Sebreli and the more recent ones of Jorge Salessi, among others—probably due to the involvement of members from both the Armed Forces and families of the oligarchy.

[78][126] In 2019, he received access to the case files—including the infamous photographs—which were long believed to be lost and had been widely sought after by gay journalists and social scientists, including Sebreli, Salessi, Osvaldo Bazán and Alejandro Modarelli.