Calgary Stampede

Organized by thousands of volunteers and supported by civic leaders, the Calgary Stampede has grown into one of the world's richest rodeos, one of Canada's largest festivals, and a significant tourist attraction for the city.

[4] By 1889, it had acquired land on the banks of the Elbow River to host the exhibitions, but crop failures, poor weather, and a declining economy resulted in the society ceasing operations in 1895.

[8] He initially failed to sell civic leaders and the Calgary Industrial Exhibition on his plans,[9] but with the assistance of local livestock agent H. C. McMullen, Weadick convinced businessmen Pat Burns, George Lane, A. J. McLean, and A. E. Cross to put up $100,000 to guarantee funding for the event.

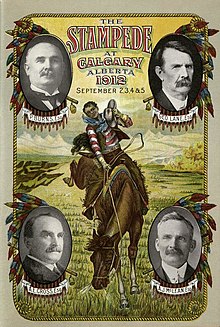

[10] The city built a rodeo arena on the fairgrounds and over 100,000 people attended the six-day event in September 1912 to watch hundreds of cowboys from Western Canada, the United States, and Mexico compete for $20,000 in prizes.

The two convinced numerous Calgarians, including the Big Four, to back the "Great Victory Stampede" in celebration of Canada's soldiers returning from World War I.

[23] Hollywood stars and foreign dignitaries were attracted to the Stampede; Bob Hope and Bing Crosby each served as parade marshals during the 1950s,[24] while Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip made their first of two visits to the event as part of their 1959 tour of Canada.

[33] The Big Four Building, named in honour of the Stampede's benefactors, opened in 1959 to serve as the city's largest exhibition hall in the summer,[24] and was converted into a 24-sheet curling facility each winter.

[33] The improvements failed to alleviate all the pressures growth had caused: chronic parking shortages and inability to accommodate demand for tickets to the rodeo and grandstand shows continued.

[34] The Saddledome replaced the Corral as the city's top sporting arena, and both facilities hosted hockey and figure skating events at the 1988 Winter Olympics.

[47] On May 26, the Alberta government announced a revised "Open for Summer" plan for easing public health orders, which would allow the majority of restrictions to be lifted two weeks after 70% of eligible residents receive at least one vaccine dose (provided that hospitalizations continue to decline).

Cowboys, First Nations dancers and members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in their red serges are joined by clowns, bands, politicians and business leaders.

[75] Officially called the Rangeland Derby, and nicknamed the "half-mile of hell"[76] or the "dash for cash",[77] chuckwagon racing proved immediately popular and quickly became the event's largest attraction.

[88] Additionally, the exhibition serves to educate the public about Alberta's ranching and agricultural heritage along with modern food production displays through events like Ag-tivity in the city.

In 1964, the Stampede Board made plans to purchase former military land (Currie Barracks) in southwest Calgary near Glenmore Trail and 24 Street and relocate the park there.

[100] Space concerns remained a constant issue, and a new plan to push northward into the Victoria Park community beginning in 1968 initiated a series of conflicts with the neighbourhood and city council that persisted for decades.

[102] With the land finally secured, the Stampede organization embarked on a $400-million expansion that is planned to feature a new retail and entertainment district, an urban park, a new agricultural arena and potentially a new hotel.

[112] First Nations people had been frequent participants in the city's exhibitions since they were first held in 1886, taking part in parades and sporting events and entertaining spectators with traditional dances.

[113] Weadick hoped to include native people as a feature of his Stampede, but Indian Affairs opposed his efforts and asked the Duke of Connaught, Canada's Governor General, to support their position.

The Duke refused, and after Weadick gained the support of political contacts in Ottawa, including future Prime Minister R. B. Bennett, the path was cleared.

[120] Complaints about low appearance fees paid to tipi owners, lack of input on committees related to their participation and accusations that natives were being exploited have periodically been made throughout the years.

[121] The Stoneys famously boycotted the 1950 Stampede following a rule change that cancelled a policy giving any Indigenous person free admittance upon showing their treaty card.

[177] People of all walks of life, from executives to students, discard formal attire for casual western dress, typically represented by Wrangler jeans and cowboy hats.

[182] The tradition of pancake breakfasts dates back to the 1923 Stampede when a chuckwagon driver by the name of Jack Morton invited passing citizens to join him for his morning meals.

Among them are the Calgary Grey Cup Committee, whose volunteers have hosted pancake breakfasts on the day of the Canadian Football League championship game for over three decades, sometimes in spite of poor weather conditions for the annual November contest.

[186] Corporations and community groups hold lavish events throughout the city for their staff and clients,[186] while bars and pubs erect party tents, the largest of which draws up to 20,000 people per day.

[188] Some parties have become known for heavy drinking and relaxed morals,[189] so much so that one hotel's satirical ad promising to safely store a patron's wedding ring during Stampede was widely viewed as a legitimate offer.

[191] Clinics see an increase in people seeking testing and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases,[190] and Calgary is said to experience an annual baby boom each April – nine months after the event.

[195] However, critics argue that it is not a reflection of Alberta's frontier history, but represents a mythical impression of western cowboy culture created by 19th-century wild west shows.

The Sun refuted charges it was kowtowing to the Stampede and justified its refusal by claiming "we are Calgarians and allowing a group of outsiders to come in and insult a proud Calgary tradition seemed just plain wrong.

[208] A 2019 Conference Board of Canada Report found the annual economic impact of the Calgary Stampede's year-round activities generated $540.8 million across the province of Alberta.