Calipers

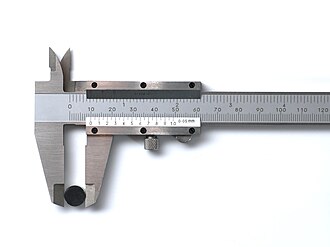

[1][2][3] Many types of calipers permit reading out a measurement on a ruled scale, a dial, or an electronic digital display.

Calipers are used in many fields such as mechanical engineering, metalworking, forestry, woodworking, science and medicine.

In loose colloquial usage, these phrases may also refer to other kinds of calipers, although they involve no vernier scale.

[5][6] A bronze caliper, dating from 9 AD, was used for minute measurements during the Chinese Xin dynasty.

With some understanding of their limitations and usage, these instruments can provide a high degree of accuracy and repeatability.

In the metalworking field, a divider caliper, popularly called a compass, is used to mark out locations.

An ECG (also EKG) caliper transfers distance on an electrocardiogram; in conjunction with the appropriate scale, the heart rate can be determined.

In the diagram at left, the uppermost caliper has a slight shoulder in the bent leg allowing it to sit on the edge more securely.

The lower caliper lacks this feature but has a renewable scriber that can be adjusted for wear, as well as being replaced when excessively worn.

The vernier, dial, and digital calipers directly read the distance measured with high accuracy and precision.

Vernier calipers commonly used in industry provide a precision to 0.01 mm (10 micrometres), or one thousandth of an inch.

The slide of a dial caliper can usually be locked at a setting using a small lever or screw; this allows simple go/no-go checks of part sizes.

A liquid-crystal display shows the measurement, which often can switch units between millimeters and fractional or decimal inches.

All provide for zeroing the display at any point along the slide, allowing the same sort of differential measurements as with the dial caliper.

The slider's circuitry counts these repetitions as it slides and achieves finer resolution using linear interpolation of the capacitances.

[19] Other digital calipers contain an inductive linear encoder, which allows robust performance in the presence of contamination such as coolants.

[citation needed] Digital calipers nowadays offer serial data output to expedite repeated measurements, avoid human error, and allow direct data entry into a digital recorder, spreadsheet, statistical process control program, or similar software on a personal computer.

Vernier calipers are rugged and have long-lasting accuracy, are coolant proof, are not affected by magnetic fields, and are largely shockproof.

In production environments, reading vernier calipers all day long is error-prone and is annoying to the workers.

Dial calipers are comparatively easy to read, especially when seeking the exact center by rocking and observing the needle movement.

They can be set to zero easily at any point with a full count in either direction and can take measurements even if the display is completely hidden, either by using a "hold" key, or by zeroing the display and closing the jaws, showing the correct measurement, but negative.

For example, when measuring the thickness of a plate, a vernier caliper must be held at right angles to the piece.

As both part and caliper are always to some extent elastic, the amount of force used affects the indication.

Whether the scale is part of the caliper or not, all analog calipers—verniers and dials—require good eyesight in order to achieve the highest precision.

Examples are a base that extends their usefulness as a depth gauge and a jaw attachment that all allows measuring the center distance between holes.

Since the 1970s, a clever modification of the moveable jaw on the back side of any caliper allows for step or depth measurements in addition to external caliper measurements, similarly to a universal micrometer (e.g., Starrett Mul-T-Anvil or Mitutoyo Uni-Mike).

Zero error may arise due to knocks that affect the calibration at 0.00 mm when the jaws are perfectly closed or just touching each other.