Luís de Camões

From this marriage were born Simão Vaz de Camões, who served in the Royal Navy and did trade in Guinea and India, and another brother, Bento, who followed the career of a man of letters and entered the priesthood, joining the Austin friars at the Monastery of Santa Cruz, which was a prestigious school for many young Portuguese gentlemen.

The trauma of the shipwreck, in the words of Leal de Matos, had the most profound impact on redefining the themes of Os Lusíadas, this being noticeable beginning with Canto VII, a fact already noted by Diogo do Couto, a friend of the poet who partly accompanied the work as it was being written.

After being embittered by the Portuguese defeat at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir, in which Sebastian disappeared, leading Portugal to lose its independence to the Spanish crown,[note 2] he was stricken by bubonic plague, according to Le Gentil.

It is said that he had great value as a soldier, exhibiting courage, combativeness, a sense of honor and willingness to serve, a good companion in his spare time, liberal, cheerful and witty when the blows of fortune did not overwhelm his spirit and sadden him.

[24] Probably executed between 1573 and 1575, the so-called "portrait painted in red", illustrated at the opening of the article, is considered by Vasco Graça Moura as "the only and precious reliable document we have to know the features of the epic, portrayed in life by a professional painter ".

[42] What is known of this portrait is a copy, made at the request of the 3rd Duke of Lafões, executed by Luís José Pereira de Resende between 1819 and 1844, from the original that was found in a green silk bag in the rubble of the fire at the palace of the Counts of Ericeira, which has since disappeared.

It is a "very faithful copy" that: [D]ue to the restricted dimensions of the drawing, the texture of the blood, creating spots of distribution of values, the rigor of the contours and the definition of the contrasted planes, the reticulated neutral that harmonizes the background and highlights the bust of the portrait, the type of the wrap around limits from which the enlightening signature runs down, in short, the symbolic apparatus of the image, captured in the pose of a graphic book illustration, was intended for the opening of an engraving on a copper plate, to illustrate one of the first editions of The Lusiads...[43]Also surviving is a miniature painted in India in 1581, by order of Fernão Teles de Meneses and offered to the viceroy D. Luís de Ataíde, who, according to testimonies of the time, was very similar to him in appearance.

[44] The first medal with its effigy appeared in 1782, ordered to mint by the Baron of Dillon in England, where Camões is crowned with laurels and dressed in coat of arms, with the inscription "Apollo Portuguez / Honor de Hespanha / Nasceo 1524 / Morreo 1579".

It was called "renaissance" due to the rediscovery and revaluation of the cultural references of Classical Antiquity, which guided the changes of this period towards a humanist and naturalist ideal that affirmed the dignity of man, placing him at the center of the universe, making him the researcher par excellence of nature, and promoting reason and science as arbitrators of manifest life.

The spirit of intellectual speculation and scientific research was on the rise, causing Physics, Mathematics, Medicine, Astronomy, Philosophy, Engineering, Philology and several other branches of knowledge to reach a level of complexity, efficiency and accuracy unprecedented, which led to an optimistic conception of human history as a continuous expansion and always for the better.

[61][63] In a way, the Renaissance was an original and eclectic attempt to harmonize pagan Neoplatonism with the Christian religion, eros with charitas, together with oriental, Jewish and Arab influences, and where the study of magic, astrology and the occult was not absent.

[64] It was also the time when strong national states began to be created, commerce and cities expanded and the bourgeoisie became a force of great social and economic importance, contrasting with the relative decline in the influence of religion in world affairs.

The result was the reaffirmation of the power of religion over the profane world and the formation of an agitated spiritual, political, social and intellectual atmosphere, with strong doses of pessimism, reverberating unfavorably on the former freedom that artists enjoyed.

Despite this, the intellectual and artistic acquisitions of the High Renaissance that were still fresh and shining before the eyes could not be forgotten immediately, even if their philosophical substrate could no longer remain valid in the face of new political, religious and social facts.

The new art that was made, although inspired by the source of classicism, translated it into restless, anxious, distorted, ambivalent forms, attached to intellectualist preciosities, characteristics that reflected the dilemmas of the century and define the general style of this phase as mannerist.

In fact, he was a master in this form, giving new life to the art of gloss, instilling in it spontaneity and simplicity, a delicate irony and a lively phrasing, taking courtesan poetry to its highest level, and showing that he also knew how to express perfectly joy and relaxation.

Through them, he managed to free himself from the formal limitations of courtesan poetry and the difficulties he went through, the profound anguish of exile, the longing for his country, indelibly impregnated his spirit and communicated with his work, and from there influenced in a marked way subsequent generations of Portuguese writers.

He dominated Latin and Spanish, and demonstrated a solid knowledge of Greco-Roman mythology, ancient and modern European history, Portuguese chroniclers and classical literature, with authors such as Ovid, Xenophon, Lucan, Valerius Flaccus, Horace standing out, but especially Homer and Virgil, from whom he borrowed various structural and stylistic elements and sometimes even passages in almost literal transcription.

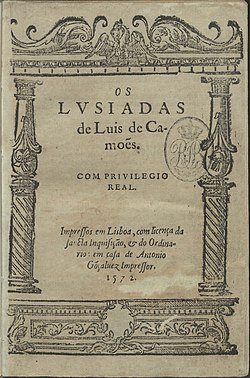

Throughout The Lusiads the signs of a political and spiritual crisis are visible, the prospect of the decline of the empire and the character of the Portuguese remains in the air, censored by bad customs and the lack of appreciation for the arts, alternating with excerpts in which its enthusiastic apology.

They are also typical of Mannerism, and would become even more Baroque, the taste for contrast, for emotional flare, for conflict, for paradox, for religious propaganda, for the use of complex figures of speech and preciousness, even for the grotesque and monstrous, many of them common features in Camonian work.

[67][69][72][73] The mannerist nature of his work is also marked by the ambiguities generated by the rupture with the past and by the concomitant adherence to it, the first manifested in the visualization of a new era and in the use of new poetic formulas from Italy, and the second, in the use of archaisms typical of the Middle Ages.

He combined typical values of humanist rationalism with other derivatives of cavalry, crusades and feudalism, aligned the constant propaganda of the Catholic faith with ancient mythology, responsible in the aesthetic plan for all the action that materializes the final realization, discarding the mediocre aurea dear to classics to advocate the primacy of the exercise of weapons and the glorious conquest.

It is a humanist epic, even in its contradictions, in the association of pagan mythology with the Christian view, in the opposite feelings about war and empire, in the taste of rest and in the desire for adventure, in the appreciation of sensual pleasure and in the demands of an ethical life, in the perception of greatness and in the presentiment of decline, in the heroism paid for with suffering and struggle.

"The feats of Arms, and famed heroick Host, from occidental Lusitanian strand, who o'er the waters ne'er by seaman crost, farèd beyond the Taprobáne-land, forceful in perils and in battle-post, with more than promised force of mortal hand; and in the regions of a distant race rear'd a new throne so haught in Pride of Place.

The cantos III, IV and V contain some of the best passages of the entire epic: the episode of Inês de Castro, which becomes a symbol of love and death, the Battle of Aljubarrota, the vision of D. Manuel I, the description of St. Elmo's fire, the story of the giant Adamastor.

[40] In Os Lusíadas, Camões achieves a remarkable harmony between classical scholarship and practical experience, developed with consummate technical skill, describing Portuguese adventures with moments of serious thought mixed with others of delicate sensitivity and humanism.

The great descriptions of the battles, the manifestation of the natural forces, the sensual encounters, transcend the allegory and the classicist allusion that permeate all the work and present themselves as a fluent speech and always of a high aesthetic level, not only for its narrative character especially well achieved, but also by the superior mastery of all the resources of the language and the art of versification, with a knowledge of a wide range of styles, used in efficient combination.

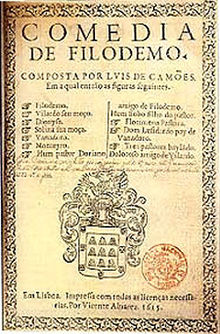

The theme, of the complicated passion of Antiochus, son of King Seleucus I Nicator, for his stepmother, Queen Estratonice, was taken from a historical fact from Antiquity transmitted by Plutarch and repeated by Petrarch and the Spanish popular songwriter, working it in the style by Gil Vicente.

The play was written in smaller redondilhas and uses bilingualism, using Castilian in the lines of the character Sósia, a slave, to mark his low social level in passages that reach the grotesque, a feature that appears in the other pieces as well.

Filodemo, composed in India and dedicated to the viceroy D. Francisco Barreto, is a comedy of morality in five acts, according to the classical division, being, of the three, the one that remained most alive in the interest of the critic due to the multiplicity of human experiences it describes and for the sharpness of psychological observation.