Seamount

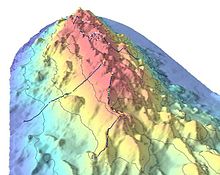

A seamount is a large submarine landform that rises from the ocean floor without reaching the water surface (sea level), and thus is not an island, islet, or cliff-rock.

Seamounts and guyots are most abundant in the North Pacific Ocean, and follow a distinctive evolutionary pattern of eruption, build-up, subsidence and erosion.

Interactions between seamounts and underwater currents, as well as their elevated position in the water, attract plankton, corals, fish, and marine mammals alike.

There are ongoing concerns on the negative impact of fishing on seamount ecosystems, and well-documented cases of stock decline, for example with the orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus).

A seamount is technically defined as an isolated rise in elevation of 1,000 m (3,281 ft) or more from the surrounding seafloor, and with a limited summit area,[5] of conical form.

[4] Most seamounts are volcanic in origin, and thus tend to be found on oceanic crust near mid-ocean ridges, mantle plumes, and island arcs.

In the North Atlantic Ocean, the New England Seamounts extend from the eastern coast of the United States to the mid-ocean ridge.

[7] Otherwise, seamounts tend not to form distinctive chains in the Indian and Southern Oceans, but rather their distribution appears to be more or less random.

[9] Their overall abundance makes them one of the most common, and least understood, marine structures and biomes on Earth,[10] a sort of exploratory frontier.

The majority of seamounts have already completed their eruptive cycle, so access to early flows by researchers is limited by late volcanic activity.

In the second, most active stage of its life, ocean-ridge volcanoes erupt tholeiitic to mildly alkalic basalt as a result of a larger area melting in the mantle.

This is finally capped by alkalic flows late in its eruptive history, as the link between the seamount and its source of volcanism is cut by crustal movement.

Some seamounts also experience a brief "rejuvenated" period after a hiatus of 1.5 to 10 million years, the flows of which are highly alkalic and produce many xenoliths.

[11] In recent years, geologists have confirmed that a number of seamounts are active undersea volcanoes; two examples are Kamaʻehuakanaloa (formerly Lo‘ihi) in the Hawaiian Islands and Vailulu'u in the Manu'a Group (Samoa).

They are the products of the explosive activity of seamounts that are near the water's surface, and can also form from mechanical wear of existing volcanic rock.

[11] Many seamounts show signs of intrusive activity, which is likely to lead to inflation, steepening of volcanic slopes, and ultimately, flank collapse.

Some species, including black oreo (Allocyttus niger) and blackstripe cardinalfish (Apogon nigrofasciatus), have been shown to occur more often on seamounts than anywhere else on the ocean floor.

Marine mammals, sharks, tuna, and cephalopods all congregate over seamounts to feed, as well as some species of seabirds when the features are particularly shallow.

[5] Seamounts often project upwards into shallower zones more hospitable to sea life, providing habitats for marine species that are not found on or around the surrounding deeper ocean bottom.

They tend to gather small particulates and thus form beds, which alters sediment deposition and creates a habitat for smaller animals.

[27] For a long time it has been surmised that many pelagic animals visit seamounts as well, to gather food, but proof of this aggregating effect has been lacking.

[29] Nearly 80 species of fish and shellfish are commercially harvested from seamounts, including spiny lobster (Palinuridae), mackerel (Scombridae and others), red king crab (Paralithodes camtschaticus), red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), tuna (Scombridae), Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), and perch (Percidae).

There are several well-documented cases of fishery exploitation, for example the orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) off the coasts of Australia and New Zealand and the pelagic armorhead (Pseudopentaceros richardsoni) near Japan and Russia.

CenSeam is intended to provide the framework needed to prioritise, integrate, expand and facilitate seamount research efforts in order to significantly reduce the unknown and build towards a global understanding of seamount ecosystems, and the roles they have in the biogeography, biodiversity, productivity and evolution of marine organisms.

Even with the right technology available,[clarification needed] only a scant 1% of the total number have been explored,[9] and sampling and information remains biased towards the top 500 m (1,640 ft).

[10] Before seamounts and their oceanographic impact can be fully understood, they must be mapped, a daunting task due to their sheer number.

Even though the ocean makes up 70% of Earth's surface area, technological challenges have severely limited the extent of deep sea mining.

An example for epithermal gold mineralization on the seafloor is Conical Seamount, located about 8 km south of Lihir Island in Papua New Guinea.

[43] More recently, the submarine USS San Francisco ran into an uncharted seamount in 2005 at a speed of 35 knots (40.3 mph; 64.8 km/h), sustaining serious damage and killing one seaman.

Subsidation analysis found that at the time of their deposition, this would have been 500 m (1,640 ft) up the flank of the volcano,[44] far too high for a normal wave to reach.