Parliament of Canada

This format was inherited from the United Kingdom and is a near-identical copy of the Parliament at Westminster, the greatest differences stemming from situations unique to Canada, such as the impermanent nature of the monarch's residency in the country and the lack of a peerage to form the upper chamber.

[8] As both the monarch and his or her representatives are traditionally barred from the House of Commons, any parliamentary ceremonies in which they are involved take place in the Senate chamber.

[12]: 51 Members of the two houses of Parliament must also express their loyalty to the sovereign and defer to his authority, as the Oath of Allegiance must be sworn by all new parliamentarians before they may take their seats.

[13][14] The upper house of the Parliament of Canada, the Senate (French: Sénat), is a group of 105 individuals appointed by the governor general on the advice of the prime minister;[15] all those appointed must, per the constitution, be a minimum of 30 years old, be a subject of the monarch, and own property with a net worth of at least $4,000, in addition to owning land worth no less than $4,000 within the province the candidate seeks to represent.

Senators may, however, resign their seats prior to that mark, and can lose their position should they fail to attend two consecutive sessions of Parliament.

The principle underlying the Senate's composition is equality amongst Canada's geographic regions (called Divisions in the Constitution): 24 for Ontario, 24 for Quebec, 24 for the Maritimes (10 for Nova Scotia, 10 for New Brunswick, and four for Prince Edward Island), and 24 for the Western provinces (six each for Manitoba, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Alberta).

An additional 4 or 8 senators may be appointed by the governor general, provided the approval of the King is secured and the four divisions are equally represented.

This power has been employed once since 1867: to ensure the passage of the bill establishing the Goods and Services Tax, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney advised Queen Elizabeth II to appoint extra senators in 1990.

The elected component of the Canadian Parliament is the House of Commons (French: Chambre des communes), with each member chosen by a plurality of voters in each of the country's federal electoral districts, or ridings.

Thus, Parliament alone can pass laws relating to, among other things, the postal service, census, military, navigation and shipping, fishing, currency, banking, weights and measures, bankruptcy, copyrights, patents, First Nations, and naturalization.

Other examples include the powers of both the federal and provincial parliaments to impose taxes, borrow money, punish crimes, and regulate agriculture.

[citation needed] The usher of the black rod of the Senate of Canada is the most senior protocol position in Parliament, being the personal messenger to the legislature of the sovereign and governor general.

The usher is also a floor officer of the Senate responsible for security in that chamber, as well as for protocol, administrative, and logistical details of important events taking place on Parliament Hill,[23] such as the Speech from the Throne, Royal Assent ceremonies, state funerals, or the investiture of a new governor general.

Upon completion of the election, the governor general, on the advice of the prime minister, then issues a royal proclamation summoning Parliament to assemble.

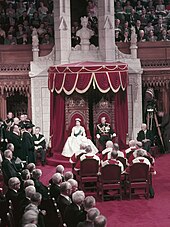

[12]: 42 The new parliamentary session is marked by the opening of Parliament, a ceremony where a range of topics can be addressed in a Speech From the Throne given by the monarch, the governor general, or a royal delegate.

[note 1] The usher of the black rod invites MPs to these events,[26] knocking on the doors of the lower house that have been slammed shut[27]—a symbolic arrangement designed to illustrate the Commons' right to deny entry to anyone, including even the monarch (but with an exception for royal messengers).

[28] Once the MPs are gathered behind the Bar of the Senate—save for the prime minister, the only MP permitted into the Senate proper to sit near the throne dais—the House of Commons speaker presents to the monarch or governor general, and formally claims the rights and privileges of the House of Commons; and then the speaker of the Senate, on behalf of the Crown, replies in acknowledgement after the sovereign or viceroy takes their seat on the throne.

[29][30][31] Both houses determine motions by voice vote; the presiding officer puts the question and, after listening to shouts of "yea" and "nay" from the members, announces which side is victorious.

Finally, the bill could be referred to an ad hoc committee established solely to review the piece of legislation in question.

In conformity with the British model, only the House of Commons may originate bills for the imposition of taxes or for the appropriation of Crown funds.

A precedent, however, was set in 1968, when the government of Lester B. Pearson unexpectedly lost a confidence vote but was allowed to remain in power with the mutual consent of the leaders of the other parties.

In practice, the House of Commons' scrutiny of the government is quite weak in comparison to the equivalent chamber in other countries using the Westminster system.

Additionally, Canada has fewer MPs, a higher turnover rate of MPs after each election, and an Americanized system for selecting political party leaders, leaving them accountable to the party membership rather than caucus, as is the case in the United Kingdom;[33] John Robson of the National Post opined that Canada's parliament had become a body akin to the American Electoral College, "its sole and ceremonial role to confirm the executive in power.

"[34] At the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, analysts—such as Jeffrey Simpson, Donald Savoie, and John Gomery—argued that both Parliament and the Cabinet had become eclipsed by prime ministerial power.

The last prime ministers to lose confidence votes were Stephen Harper in 2011, Paul Martin in 2005 and Joe Clark in 1979, all involving minority governments.

[42] Following the cession of New France to the United Kingdom in the 1763 Treaty of Paris, Canada was governed according to the Royal Proclamation issued by King George III in that same year.

To this was added the Quebec Act, by which the power to make ordinances was granted to a governor-in-council, both the governor and council being appointed by the British monarch in Westminster, on the advice of his or her ministers there.

During the War of 1812, American troops set fire to the buildings of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada in York (now Toronto).

The actual site of Parliament shifted on a regular basis: From 1841 to 1844, it sat in Kingston, where the present Kingston General Hospital now stands; from 1844 until the 1849 fire that destroyed the building, the legislature was in Montreal; and, after a few years of alternating between Toronto and Quebec City, the legislature was finally moved to Ottawa in 1856, Queen Victoria having chosen that city as Canada's capital in 1857.

While her father, King George VI, had been the first Canadian monarch to grant royal assent in the legislature—doing so in 1939—Queen Elizabeth II was the first sovereign to deliver the speech from the throne.