Canadian Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic is a member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages and the Canadian dialects have their origins in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland.

At its peak in the mid-19th century, there were as many as 200,000 speakers of Scottish Gaelic and Newfoundland Irish together, making it the third-most-spoken European language in Canada after English and French.

[8][9] The 2016 Canadian census also reported that 240 residents of Nova Scotia and 15 on Prince Edward Island considered Scottish Gaelic to be their "mother tongue".

Thousands of Nova Scotians attend Gaelic-related activities and events annually including: language workshops and immersions, milling frolics, square dances, fiddle and piping sessions, concerts and festivals.

Gaels, and their language and culture, have influenced the heritage of Glengarry County and other regions in present-day Ontario, where many Highland Scots settled commencing in the 18th century, and to a much lesser extent the provinces of New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador (especially the Codroy Valley), Manitoba and Alberta.

Those who intermarried with the local First Nations people passed on their language, with the effect that by the mid-18th century there existed a sizeable population of Métis traders with Scottish and aboriginal ancestry, and command of spoken Gaelic.

[18] They would remember Canada when the earliest of the Highland Clearances by the increasingly Anglicized Scottish nobility began to evict Gaelic-speaking tenants en masse from their ancestral lands in order to replace them with private deer-stalking estates and herds of sheep.

[19] In 1784 the last barrier to Scottish settlement – a law restricting land-ownership on Cape Breton Island – was repealed, and soon both PEI and Nova Scotia were predominantly Gaelic-speaking.

[22] Ailean a' Ridse MacDhòmhnaill (Allan The Ridge MacDonald) emigrated with his family from Ach nan Comhaichean, Glen Spean, Lochaber to Mabou, Nova Scotia in 1816 and composed many works of Gaelic poetry as a homesteader in Cape Breton and in Antigonish County.

[23] According to Michael Newton, however, A' Choille Ghruamach, which is, "an expression of disappointment and regret", ended upon becoming, "so well established in the emigrant repertoire that it easily eclipses his later songs taking delight in the Gaelic communities in Nova Scotia and their prosperity.

"[24] In the Highlands and Islands, MacLean is commonly known as "The Poet to the Laird of Coll" (Bàrd Thighearna Chola) or as "John, son of Allan" (Iain mac Ailein).

These settlers arrived on a mass scale at the arable lands of British North America, with large numbers settling in Glengarry County in present-day Ontario, and in the Eastern Townships of Quebec.

However poor the family (but indeed there are none that can be called so) they kill a bullock for the winter consumption; the farm or estate supplies them with abundance of butter, cheese, etc., etc.

[27] In 1812, Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk obtained 300,000 square kilometres (120,000 sq mi) to build a colony at the forks of the Red River, in what would become Manitoba.

The settlement soon attracted local First Nations groups, resulting in an unprecedented interaction of Scottish (Lowland, Highland, and Orcadian), English, Cree, French, Ojibwe, Saulteaux, and Métis traditions all in close contact.

Used primarily by the Anglo– and Scots–Métis traders, the "Red River Dialect" or Bungi was a mixture of Gaelic and English with many terms borrowed from the local native languages.

[3][31] In 1890, Thomas Robert McInnes, an independent Senator from British Columbia (born Lake Ainslie, Cape Breton Island) tabled a bill entitled "An Act to Provide for the Use of Gaelic in Official Proceedings.

Murdoch Lamont (1865–1927), a Gaelic-speaking Presbyterian minister from Orwell, Queen's County, Prince Edward Island, published a small, vanity press booklet titled, An Cuimhneachain: Òrain Céilidh Gàidheal Cheap Breatuinn agus Eilean-an-Phrionnsa ("The Remembrance: Céilidh Songs of the Cape Breton and Prince Edward Island Gaels") in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Gaelic has faced widespread prejudice in Great Britain for generations, and those feelings were easily transposed to British North America.

[35] The fact that Gaelic had not received official status in its homeland made it easier for Canadian legislators to disregard the concerns of domestic speakers.

'The Woman who Lost the Gaelic', also known in English as "The Yankee Girl"), a humorous song recounting the growing phenomenon of Gaels shunning their mother-tongue.

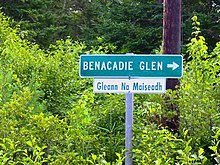

[3] There are no longer entire communities of Canadian Gaelic-speakers, although traces of the language and pockets of speakers are relatively commonplace on Cape Breton, and especially in traditional strongholds like Christmas Island, The North Shore, and Baddeck.

[41] Many English-speaking writers and artists of Scottish-Canadian ancestry have featured Canadian Gaelic in their works, among them Alistair MacLeod (No Great Mischief), Ann-Marie MacDonald (Fall on Your Knees), and D.R.

Gaelic singer Mary Jane Lamond has released several albums in the language, including the 1997 hit Hòro Ghoid thu Nighean ('Jenny Dang the Weaver').

"[39] While performing in 2000 at the annual Cèilidh at Christmas Island, Cape Breton, Barra native and legendary Gaelic singer Flora MacNeil spread her arms wide and cried, "You are my people!"

During his employment as Professor of Gaelic Studies at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nilsen was known for his contagious enthusiasm for both teaching and recording the distinctive Nova Scotia dialect of the Gaelic-language, its folklore, and its oral literature.

[46] During his time as Professor of Gaelic Studies, Nilsen would take his students every year to visit the grave of the Tiree-born Bard Iain mac Ailein (John MacLean) (1787–1848) at Glenbard, Antigonish County, Nova Scotia.

In Prince Edward Island, the Colonel Gray High School now offers both an introductory and an advanced course in Gaelic; both language and history are taught in these classes.

These two documents are watersheds in the timeline of Canadian Gaelic, representing the first concrete steps taken by a provincial government to recognize the language's decline and engage local speakers in reversing this trend.

Reading, writing and grammar are introduced after the student has had a minimum amount of exposure to hearing and speaking Gaelic through everyday contextualized activities.