Canadian comics

The alternative and small press communities grew in the 1970s, and by the end of the century Dave Sim's Cerebus and Chester Brown's comics, amongst others, gained international audiences and critical acclaim, and Drawn & Quarterly became a leader in arts-comics publishing.

[8] Palmer Cox, a Canadian expatriate in the United States, at this time created The Brownies, a popular, widely merchandised phenomenon whose first book collection sold over a million copies.

One was Buck Rogers; the other, Tarzan, by Halifax native Hal Foster, who had worked as illustrator for catalogues from Eaton's and the Hudson's Bay Company before moving to the US in his late 20s.

[12] After struggling to support himself at various Toronto-based publications,[13] Richard Taylor, under the pen name "Ric", became a regular at The New Yorker[14] and relocated to the US, where the pay and opportunities for cartoonists were better.

[21] The driving creative forces behind Anglo-American were Ted McCall, the writer of the Men of the Mounted and Robin Hood strips, and artist Ed Furness.

Anglo-American also published stories based on imported American scripts bought from Fawcett Publications, with fresh artwork by Canadians to bypass trade restrictions.

[25] The popular fur-miniskirted superheroine was a powerful Inuit mythological figure, daughter of a mortal woman and Koliak the Mighty, King of the Northern Lights.

Educational specialized in a different sort of fare: biographies of prime ministers, cases of the RCMP, and historical tales, drawn by accomplished artists including George M. Rae and Sid Barron.

Some of Superior's titles found themselves in Fredric Wertham's notorious and influential diatribe on the influence comics had on juvenile delinquency, Seduction of the Innocent, published in 1954.

The United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, established in 1953, had public hearings a few months later, and called upon Kamloops, British Columbia Member of Parliament E. Davie Fulton, one of Superior publisher William Zimmerman's most outspoken enemies, as a witness.

[32] The crackdown was not aimed at comic strips, however, and several notable new ones appeared, like Lew Saw's One-Up, Winslow Mortimer's Larry Brannon and Al Beaton's Ookpik.

[35] To express his anger at the US military's nuclear tests in the Bikini Atoll in 1946 English-born artist Laurence Hyde produced a wordless novel in 1951 called Southern Cross.

[3] In the spring of 1966, Canada saw its first specialty comic shop open its doors on Queen Street West, Toronto: Viking Bookshop, established by "Captain George" Henderson.

[44] This was followed up with James Waley's more professional, newsstand-distributed Orb, which featured a number of talents that would later take part in the North American comics scene.

The strip based a number of its storylines on Johnston's real-life experiences with her own family, as well as social issues such as the midlife crisis, divorce, the coming out of a gay character,[2] child abuse, and death.

The story eventually grew to fit Sim's expanding ambitions, both in content and technique, with its earth-pig protagonist getting embroiled in politics, becoming prime minister of a powerful city-state, then a Pope who ascends to the moon—all within the first third of its projected 300-issue run.

Sim came to conceive the series as a self-enclosed story, which itself would be divided into novels—or graphic novels, which were gaining in prominence in the North American comic book world in the 1980s and 1990s.

Americans Jeff Smith with Bone and Terry Moore with Strangers in Paradise took Sim's cue, as did Canadian M'Oak (Mark Oakley) with his long-running Thieves and Kings.

The publisher gained publicity for Mister X, which employed the talents of Dean Motter, Gilberto and Jaime Hernandez and, later, Torontonians Seth and Jeffrey Morgan.

[47] During this time, large numbers of Canadian artists were making waves in the American comic book market as well, such as John Byrne, Gene Day and his brother Dan, Jim Craig, Rand Holmes, Geof Isherwood, Ken Steacy, Dean Motter, George Freeman and Dave Ross.

[2] These comics had artistic aspirations,[57] and graphic novels became increasingly prominent, with Brown's autobiographical The Playboy and I Never Liked You, and Seth's faux-autobiographical It's a Good Life, If You Don't Weaken garnering considerable attention.

[59] A number of early webcomics were created by Canadian authors, such as Space Moose by Adam Thrasher, Bob the Angry Flower by Stephen Notley, User Friendly by J.D.

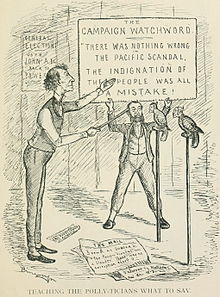

Louis Riel, who had been a major target of John Bengough's caricatures in the early days of Confederation, was the protagonist in Chester Brown's award-winning, best-selling[60] "comic-strip biography".

In the late 19th century, Henri Julien published two books of political caricatures, L'album drolatique du journal Le Farceur, after which the number of cartoonists began to increase in newspapers in Québec City and Montreal.

[79] In 1979, Jacques Hurtubise, Pierre Huet and Hélène Fleury would establish the long-lived, satirical Croc, which published many leading talents of the era, many of whom were able to launch their careers through the magazine's help.

Julie Doucet, Henriette Valium, Luc Giard, Éric Thériault, Gavin McInnes and Siris were among the names that were discovered in the small press publications.

[76] In the 21st century, Michel Rabagliati and his semi-autobiographical Paul series has seen Tintin-like sales levels in Québec, and his books have been published in English by Drawn & Quarterly.

The small press has played an important rôle;[54] self-publishing is a common means of putting out comics, largely influenced by the success of Dave Sim's Cerebus.

The National Newspaper Awards was established in 1949[80] with a category for Editorial Cartooning[8] honouring those that "embody an idea made clearly apparent, good drawing, and striking pictorial effect in the public interest".

[87] Canadian feminist scholars such as Mary Louise Adams, Mona Gleason, and Janice Dickin McGinnis have done research into the anti-crime comics campaigns of the late 1940s and 1950s, from the point of view of the moral panic and social and legal history of the era, and the sociology of sexuality.