John Wilson Bengough

John Wilson Bengough (/ˈbɛŋɡɒf/;[1] 7 April 1851 – 2 October 1923) was one of Canada's earliest cartoonists, as well as an editor, publisher, writer, poet, entertainer, and politician.

Born in Toronto in the Province of Canada to Scottish and Irish immigrants, Bengough grew up in nearby Whitby, where after graduating from high school he began a career in newspapers as a typesetter.

After Grip folded in 1894, Bengough published books, contributed cartoons to Canadian and foreign newspapers, and toured giving chalk talks internationally.

[2] Bengough's father married Margaret Wilson, an Irish immigrant[4] born in Bailieborough in County Cavan,[5] and the couple had six children: five sons and a daughter.

[5] Bengough attended Whitby Grammar School, where he was an average student;[6] he won a prize one year for general proficiency, for which he received a book titled Boyhood of Great Artists.

Bengough reminisced, I divided my time between mechanical duties for sordid wages and poetry for the good of humanity, and meanwhile I kept an eye on Thomas Nast the cartoonist.

[20] The lack of cartooning opportunities disappointed him, and he enrolled briefly in the Ontario School of Art, which he found pedantic and stifling;[16] he quit after one term.

[20] The legitimate forces of humor and caricature can and ought to serve the state in its highest interests, and that the comic journal which has no other aim than to amuse its readers for the moment, falls short of its highest mission.Bengough told the following story of how he took up publishing: He had made a caricature of James Beaty, Sr., editor of the conservative Toronto Leader, and Beaty's nephew Sam found it so amusing that he made a lithographic copy for himself at the printer Rolph Bros.

[23] In 1849–50[24] John Henry Walker's short-lived weekly Punch in Canada provided the first regular outlet for Canadian political cartooning;[b][26] others such as The Grumbler (1858–69), Grinchuckle (1869–70), and Diogenes (1868–70) did not last long, either.

Its pages carried political and social commentary along with satirical cartoons, and its debut issue of 24 May 1873 declared: "Grip will be entirely independent and impartial, always, and on all subjects."

[35] In March 1874, in the music hall of the Toronto Mechanics' Institute,[d] Bengough began giving comic chalk talk performances,[41] which he later toured across the country.

[48] Years later, Bengough's brother Thomas blamed the board of directors at Grip, Inc., for the falling out over "general mismanagement",[49] which may have involved losses incurred in relation to a government contract.

[4] He counted future Toronto mayor Horatio Clarence Hocken amongst his reformist allies on the Council[57] and promoted issues such as public ownership of hydroelectric power, but found little support for his ideas.

[4] Following a chalk-talk performance in Moncton, New Brunswick in 1922, Bengough suffered an attack of angina pectoris, attributed to overwork during a previous tour of Western Canada.

He died of it on 2 October 1923[18] at his drawing board at his home on 58 St Mary Street in Toronto while working on a cartoon in support of an anti-smoking campaign.

[4] At his memorial service on 22 November, the editor of the Hamilton Herald, Albert E. S. Smythe, declared him the "Canadian Dickens" and one of Walt Whitman's "great companions".

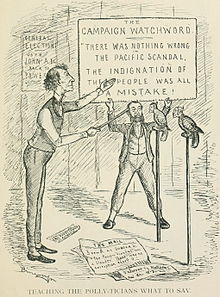

[4] As typical of political cartoonists of the time, Bengough aimed less at laughter than at social satire and depended more on readers' understanding of densely packed allusions.

[4] Bengough's bulbous-nosed[66] politician often appeared baggy-eyed with bottles of alcohol in his hands as a sombre symbol of corruption, in contrast to the work of John Henry Walker, another prolific caricaturist of Macdonald who depicted the prime minister's drunkenness to make light of him.

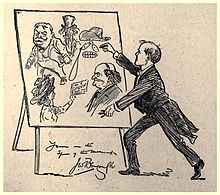

Bengough delivered humorous anecdotes and made impressions as he caricatured audience members and well-known locals in a flamboyant manner, adding the identifying details only at the end.

[43] There was a premier named John A.Who, wishing in office to stay,To one Allen did barter a great railway charter—And dated his ruin from that day.Bengough's reputation was as a supporter of the Liberal Party of Canada and its pro-democratic platform.

[17] Bengough was a proponent of such issues as proportional representation, prohibition of alcohol and of tobacco, the single tax[18] espoused by Henry George, and worldwide free trade.

[78] While Bengough sympathized with the plight of Canada's native peoples, he condemned the 1885 North-West Rebellion and called for the execution of Métis rebel leader Louis Riel, and celebrated Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton's victory at the Battle of Batoche in Saskatchewan with a poem.

[4] His racial caricatures could, according to Carman Cumming, lead a modern reader to see him as "a racist chauvinist bigot":[79] they distort facial features and behaviour in ways typical of cartoons of the era and employ such derogatory terms as "coon" for blacks and "sheeny" for Jews.

[86] The editor of Canadian Methodist Magazine William Henry Withrow declared Bengough "an Artist of Righteousness"[87] who was "always on the right side of every moral question".

[88] The church minister and Queen's College principal George Monro Grant called Bengough "the most honest interpreter of current events [Canada happens] to have" and declared he had "no malice in him" but had "a merry heart, and that doeth good like medicine".

[90] Bengough's caricatures continue to illustrate Canadian texts[71]—examples in which they are prominent include Creighton's biography John A. Macdonald (1952–55), Armstrong and Nelles' The Revenge of the Methodist Bicycle Company: Sunday Streetcars and Municipal Reform in Toronto, 1888–1897 (1977), and Waite's Arduous Destiny: Canada 1874–1896 (1971).

[4] To Peter Desbarats and Terry Mosher, Bengough's bulbous-nosed caricatures of Macdonald as "ungainly, boozy, and corrupt ... engraved itself on the public mind, particularly in the days before newspapers published photographs of politicians".

[54] Historian George Ramsay Cook commended Bengough's approach to have "nurtured the growth of social criticism in late Victorian Canada without much of that humourless self-righteousness that so often characterizes reformers".

[95] On 19 May 1938, the Canadian government listed Bengough as a Person of National Historic Significance and dedicated a plaque to him at 66 Charles Street East in Toronto.

The opera may have been an earlier version of Puffe and Co., or Hamlet, Prince of Dry Goods, for which an undated and possibly unpublished script exists, and for which Clarence Lucas had written a score that Bengough appears to have rejected.

(18 August 1871)

(16 August 1873)

(29 August 1885)