Canadian federalism

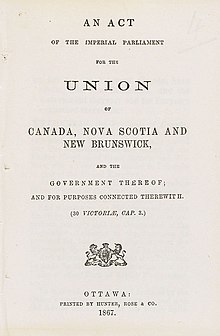

Some amendments to the division of powers have been made in the past century and a half, but the 1867 act still sets out the basic framework of the federal and provincial legislative jurisdictions.

This process was dominated by John A. Macdonald, who joined British officials in attempting to make the federation more centralized than that envisaged by the Resolutions.

In a series of political battles and court cases from 1872 to 1896,[a] Mowat reversed Macdonald's early victories and entrenched the co-ordinated sovereignty which he saw in the Quebec Resolutions.

[b] The constitution's restrictions of parliamentary power were affirmed in 1919 when, in the Initiatives and Referendums Reference, a Manitoba act providing for direct legislation by way of initiatives and referendums was ruled unconstitutional by the Privy Council on the grounds that a provincial viceroy (even one advised by responsible ministers) could not permit "the abrogation of any power which the Crown possesses through a person directly representing it".

All three bills were later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Canada in Reference re Alberta Statutes, which was upheld by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

Frank Lindsay Bastedo, Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan, withheld Royal Assent and reserved Bill 5, An Act to Provide for the Alteration of Certain Mineral Contracts, to the Governor-in-Council for review.

The National Energy Program and other petroleum disputes sparked bitterness in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland toward the federal government.

[12] Although Canada achieved full status as a sovereign nation in the Statute of Westminster 1931, there was no consensus on a process to amend the constitution; attempts such as the 1965 Fulton–Favreau formula and the 1971 Victoria Charter failed to receive unanimous approval from both levels of government.

[13] Manitoba, Newfoundland and Quebec posed reference questions to their respective courts of appeal, in which five other provinces intervened in support.

"[13] Officials in the United Kingdom indicated that the British parliament was under no obligation to fulfill a request for legal changes desired by Trudeau, particularly if Canadian convention was not followed.

The Progressive Conservative Party under Joe Clark and Brian Mulroney favoured the devolution of power to the provinces, culminating in the failed Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords.

After the 1995 Quebec referendum on sovereignty, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien limited the ability of the federal government to spend money in areas under provincial jurisdiction.

The Act puts remedial legislation on education rights, uniform laws relating to property and civil rights (in all provinces other than Quebec), creation of a general court of appeal and other courts "for the better Administration of the Laws of Canada," and implementing obligations arising from foreign treaties, all under the purview of the federal legislature in Section 91.

Jurisdiction over Crown property is divided between the provincial legislatures and the federal parliament, with the key provisions Sections 108, 109, and 117 of the Constitution Act, 1867.

[nb 23] Canada cannot unilaterally create Indian reserves, since the transfer of such lands requires federal and provincial approval by Order in Council (although discussion exists about whether this is sound jurisprudence).

[nb 32] Federal-provincial management agreements have been implemented concerning offshore petroleum resources in the areas around Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia.

In Allard Contractors Ltd. v. Coquitlam (District), provincial legislatures may levy an indirect fee as part of a valid regulatory scheme.

[nb 33] Gérard La Forest observed obiter dicta that section 92(9) (with provincial powers over property and civil rights and matters of a local or private nature) allows for the levying of license fees even if they constitute indirect taxation.

Although the Supreme Court of Canada has not ruled directly about constitutional limits on federal spending power,[nb 34][31] parliament can transfer payments to the provinces.

[nb 37] Much distribution of power has been ambiguous, leading to disputes which have been decided by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council and (after 1949) the Supreme Court of Canada.

[nb 39][d][e] The national-concern doctrine is governed by the principles stated by Mr Justice Le Dain in R. v. Crown Zellerbach Canada Ltd..[nb 41][f] The federal government is partially limited by powers assigned to the provincial legislatures; for example, the Canadian constitution created broad provincial jurisdiction over direct taxation and property and civil rights.

In the Local Prohibition Case of 1896, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council arrived at a method of interpretation, known as the "four-departments doctrine", in which jurisdiction over a matter is determined in the following order:[nb 42] By the 1930s, as noted in the Fish Canneries Reference and Aeronautics Reference, the division of responsibilities between federal and provincial jurisdictions was summarized by Lord Sankey.

[g] Although the Statute of Westminster 1931 declared that the Parliament of Canada had extraterritorial jurisdiction, the provincial legislatures did not achieve similar status.

Section 129 of the Constitution Act, 1867 provided for laws in effect at the time of Confederation to continue until repealed or altered by the appropriate legislative authority.

"[nb 46] Chief Justice Dickson observed the complexity of that interaction: The history of Canadian constitutional law has been to allow for a fair amount of interplay and indeed overlap between federal and provincial powers.

[nb 59] Although the reasoning behind the judgments is complex,[44] it is considered to break down as follows: Although the Statute of Westminster 1931 had made Canada fully independent in governing its foreign affairs, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council held that s. 132 did not evolve to take that into account.

As noted by Lord Atkin at the end of the judgment, It must not be thought that the result of this decision is that Canada is incompetent to legislate in performance of treaty obligations.

While the ship of state now sails on larger ventures and into foreign waters she still retains the watertight compartments which are an essential part of her original structure.

This case left undecided the extent of federal power to negotiate, sign and ratify treaties dealing with areas under provincial jurisdiction, and has generated extensive debate about complications introduced in implementing Canada's subsequent international obligations;[45][46] the Supreme Court of Canada has indicated in several dicta that it might revisit the issue in an appropriate case.

[47] Outside the questions of ultra vires and compliance with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, there are absolute limits on what the Parliament of Canada and the provincial legislatures can legislate.