Canis

Species of this genus are distinguished by their moderate to large size, their massive, well-developed skulls and dentition, long legs, and comparatively short ears and tails.

[3] The genus Canis (Carl Linnaeus, 1758) was published in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae[2] and included the dog-like carnivores: the domestic dog, wolves, coyotes and jackals.

[11] The fossil record shows that feliforms and caniforms emerged within the clade Carnivoramorpha 43 million YBP.

By 5 million YBP the larger Canis lepophagus, ancestor of wolves and coyotes, appeared in the same region.

[1]: p58 Around 5 million years ago, some of the Old World Eucyon evolved into the first members of Canis,[14] and the position of the canids would change to become a dominant predator across the Palearctic.

This was followed by an explosion of Canis evolution across Eurasia in the Early Pleistocene around 1.8 million YBP in what is commonly referred to as the wolf event.

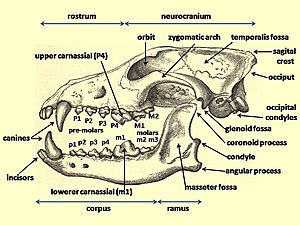

In carnivores, the upper premolar P4 and the lower molar m1 form the carnassials that are used together in a scissor-like action to shear the muscle and tendon of prey.

[18] A study of the estimated bite force at the canine teeth of a large sample of living and fossil mammalian predators, when adjusted for their body mass, found that for placental mammals the bite force at the canines (in Newtons/kilogram of body weight) was greatest in the extinct dire wolf (163), followed among the modern canids by the four hypercarnivores that often prey on animals larger than themselves: the African hunting dog (142), the gray wolf (136), the dhole (112), and the dingo (108).

Wolves, dholes, coyotes, and jackals live in groups that include breeding pairs and their offspring.

Wolves are typically monogamous and form pair-bonds; whereas dogs are promiscuous when free-range and mate with multiple individuals.

This shows that the food-for-sex hypothesis likely plays a role in the food sharing among canids and acts as a direct benefit for the females.

[27] Another study on free-ranging dogs found that social factors played a significant role in the determination of mating pairs.

[30] Due to the high mortality of free-range dogs at a young age a mother's fitness can be drastically reduced.

A study done in 2017 found that aggression between male and female gray wolves varied and changed with age.

This requires further research but suggests that intersexual aggression levels in gray wolves relates to their mating system.

The solitary hunter depends on a powerful bite at the canine teeth to subdue their prey, and thus exhibits a strong mandibular symphysis.

The highest frequency of breakage occurred in the spotted hyena, which is known to consume all of its prey including the bone.

[32][34] The eating of bone increases the risk of accidental fracture due to the relatively high, unpredictable stresses that it creates.

Canines are the teeth most likely to break because of their shape and function, which subjects them to bending stresses that are unpredictable in direction and magnitude.