Beringian wolf

In 2016, a study showed that some of the wolves now living in remote corners of China and Mongolia share a common maternal ancestor with one 28,000-year-old eastern Beringian wolf specimen.

[2] However, no type specimen, description nor exact location was provided, and because dire wolves had not been found this far north this name was later proposed as nomen nudum (invalid) by the paleontologist Ronald M.

[3] Between 1932 and 1953 twenty-eight wolf skulls were recovered from the Ester, Cripple, Engineer, and Little Eldorado creeks located north and west of Fairbanks.

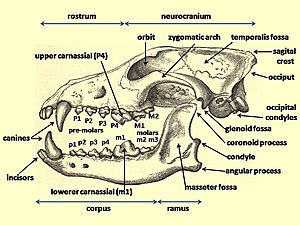

The geologist and paleontologist Theodore Galusha, who helped amass the Frick collections of fossil mammals at the American Museum of Natural History, worked on the wolf skulls over a number of years and noted that, compared with modern wolves, they were "short-faced".

[8] As of 2020, the oldest known intact wolf remains belongs to a mummified pup dated 56,000 YBP that was recovered from the permafrost along a small tributary of Last Chance Creek near Dawson City, Yukon, Canada.

The ancient wolf samples from western Europe differed from modern wolves by 1 to 10 mutations, and all belonged to haplogroup 2, indicating its predominance in this region for over 40,000 years, both before and after the Last Glacial Maximum.

[21] A scenario consistent with the phylogenetic, ice sheet size, and sea-level depth data is that during the Late Pleistocene the sea levels were at their lowest.

Another wolf from the Vypustek cave, Czech Republic, dated 44,000 YBP had a mDNA sequence identical to two Beringian wolves (indicating another common maternal ancestor).

[23] The Beringian wolf became extinct, and the southern wolves expanded through the shrinking ice sheets to recolonize the northern part of North America.

lupus...Examination of a large series of recent wolf skulls from the Alaskan area did not produce individuals with the same variations as those from the Fairbanks gold fields.

[27][37][38] In the Late Pleistocene the variations between local environments would have encouraged a range of wolf ecotypes that were genetically, morphologically, and ecologically distinct from each another.

[39] The Beringian wolf ecomorph shows evolutionary craniodental plasticity not seen in past nor present North American gray wolves,[8] and was well-adapted to the megafauna-rich environment of the Late Pleistocene.

[42] The fossil evidence from many continents points to the extinction of large animals, termed Pleistocene megafauna, near the end of the last glaciation.

[43] During the Ice Age a vast, cold and dry mammoth steppe stretched from the Arctic islands southwards to China, and from Spain eastwards across Eurasia and over the Bering land bridge into Alaska and the Yukon, where it was blocked by the Wisconsin glaciation.

The land bridge existed because sea levels were lower due to more of the planet's water being locked up in glaciers compared with today.

[44][45] In eastern Beringia from 35,000 YBP the northern Arctic areas experienced temperatures 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) warmer than today, but the southern sub-Arctic regions were 2 °C (3.6 °F) cooler.

[46] Beringia received more moisture and intermittent maritime cloud cover from the north Pacific Ocean than the rest of the Mammoth steppe, including the dry environments on either side of it.

[44][45] In this Beringian refugium, eastern Beringia's vegetation included isolated pockets of larch and spruce forests with birch and alder trees.

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) and woodland muskox (Symbos cavifrons) consumed tundra plants, including lichen, fungi, and mosses.

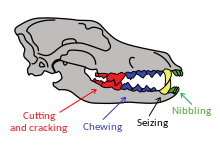

The Beringian wolf's short, broad rostrum increased the force of a bite made with the canine teeth while strengthening the skull against the stresses caused by struggling prey.

Today, the relatively deep jaws similar to those of the Beringian wolf can be found in the bone-cracking spotted hyena and in those canids that are adapted for taking large prey.

[8][16] An accepted sign of domestication is the presence of tooth crowding, in which the orientation and alignment of the teeth are described as touching, overlapping or being rotated.

However, a 2017 study found that 18% of Beringian wolf specimens exhibit tooth crowding compared with 9% for modern wolves and 5% for domestic dogs.

The study indicates that tooth crowding can be a natural occurrence in some wolf ecomorphs and cannot be used to differentiate ancient wolves from early dogs.

When there is low prey availability, the competition between carnivores increases, causing them to eat faster and consume more bone, leading to tooth breakage.

[8] This proposal was challenged in 2019, when a survey of modern wolf behavior over the past 30 years showed that when there was less prey available, the rates of tooth fracture more than doubled.

The factors that affect biogeographic range and population size include competition, predator-prey interactions, variables of the physical environment, and chance events.

[71][72] The cause of the extinction of this megafauna is debated[58] but has been attributed to the impact of climate change, competition with other species, including humans, or a combination of both factors.

[58][73] For those mammals with modern representatives, ancient DNA and radiocarbon data indicate that the local genetic populations were replaced by others from within the same species or by others of the same genus.

The most genetically basal coyote mDNA clade pre-dates the Late Glacial Maximum and is a haplotype that can only be found in the Eastern wolf.