Capitalocene

Frequently misunderstood as an alternative geological periodization to the Anthropocene proposal, the Capitalocene's leading proponents argue for the centrality of capitalism in the making of climate crisis.

This critique of Man versus Nature thinking allows the Capitalocene thesis to move beyond theory, and reconstruct a history of the origins of planetary crisis rooted in imperialism, class struggle, and world accumulation, all with and within webs of life.

In this approach, class and capital are not only driving forces of planetary crisis, but "guiding threads" for the investigation of power, profit and life in the modern world—and for the elaboration of a socialist climate politics in the twenty-first century.

The topic was an occasional theme in their later writing, as seen most notably in Marx's exploration of “social metabolism” and Engels' passage on the “revenge of nature.”[17] Although this facet of their work was long neglected, the rise of the environmental movement in the late twentieth century provoked a new interest in these passages and in environmental questions more generally among Marxist scholars of that time, exemplified by James O'Connor's theory of the “second contradiction of capitalism” and John Bellamy Foster's exegesis of Marx's “metabolic rift.” As Crutzen's framework spread among natural scientists and filtered down to the wider public, it attracted the attention of social scientists from this and the related ecofeminist school.

The Capitalocene begins not with the invention of Watt's steam engine, but with its ascendancy as the main source of power for the British cotton industry in the second quarter of the nineteenth century.

[25] [b] Fossil Capital argues that steam power's real advantage at the time and place of its adoption was the degree of control over production it gave to British textile mill owners.

Adoption of new technology is typically assumed to be driven by its potential to reduce wage expenses; in the case of weaving, however, mechanization was actually caused by the extremely low cost of labor power.

Following the Panic of 1825, weavers' wages plummeted to bare subsistence level; this, however, compelled weavers—who generally worked from home, without continual supervision—to make a living by embezzling their product and selling it on the side, incurring losses to their employers.

While the exact reason for the cancellation of these projects is uncertain due to the loss of relevant documents, Malm argues that it was fundamentally a collective action problem: manufacturers were not willing to make a necessary large, pooled investment that might benefit their competitors more than them,[c] and which would be controlled by a joint association rather than within the confines of their own mill.

[27] In sum, Malm's thesis is that the rise of fossil fuels was not a collective decision of mankind nor the inevitable result of its nature, but the outcome of specific dynamics of capitalist production.

[28] Such appropriation is itself only possible because of an ideological development of the early modern era that posited a newly absolute conceptual division between society and nature, which Moore equates with Cartesian dualism.

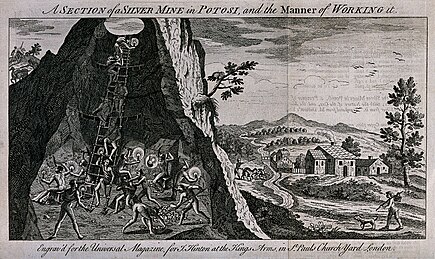

Among the developments of this period were the sudden and rapid deforestation of the Baltic region, Dutch land reclamation, the explosion of mining in Central Europe and the Andes, and the enslavement of human beings relegated to the category of “nature” rather than “society.”[31] It is a mistake, says Moore, to consider the rise of steam industry or the increasing levels of carbon in the geologic record in the 19th century as the beginning of the Capitalocene, because these were merely the delayed effects of a system which emerged centuries earlier.

[34] Although Haraway considers the Capitalocene the most appropriate term for our era,[35] she distances herself from any version of it “told in the idiom of fundamentalist Marxism, with all its trappings of Modernity, Progress, and History”; in short, from its articulation as an overly grand narrative.

But the world that Lancashire founded in the 1830s encompasses us all as the ecological reality we have to deal with.”[43] Moore's response is to consider Eastern Bloc states semi-peripheral territories of the capitalist world-system, and thus a part of the Capitalocene in their own way.

In L'Emballement du monde, a social history of energy exploitation, IFP School professor Victor Court evaluates and ultimately rejects the Capitalocene.

Beyond this, he too raises the objection of twentieth century socialism's environmental record, and is not persuaded by Malm's aforementioned rejoinder: to concede that other economic systems contributed to climate change is to undermine the whole Capitalocene premise.