Capture of Columbia

Columbia was of considerable strategic importance: it was a center of manufacturing, a rail hub, a state capital, and a symbolic origin point of the secession movement.

No preparations had been made for the evacuation of the city's citizens, army materiel, or administrative functions (including the Confederate treasury's printing presses).

Undisciplined Union soldiers complicated firefighting efforts, as rogue elements of the army were generally looting the city, and some were setting fires.

Combined with the Union blockade of the South, Columbian warehouses, and even basements and outbuildings of unrelated properties, were packed full of cotton.

Secession may well have been declared in Columbia, were it not for a smallpox outbreak which moved the convention partway through to Charleston, where South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union on December 20.

The grounds of the University of South Carolina were converted into a military hospital, since its role as an educational institution had been made moot after its entire student body volunteered for the Confederate Army.

[8] The city's most important industrial contribution was the Palmetto Iron Works, which in concert with a nearby gunpowder factory, manufactured shells, bullets, and cannons.

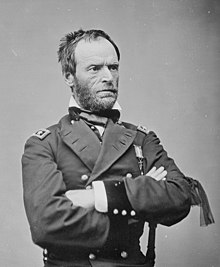

[11] Following the fall of Savannah, Georgia, at the end of his March to the Sea, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman turned his combined armies northward to unite with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia and to cut General Robert E. Lee's supply lines to the Deep South.

He hoped that doing so would give the Confederacy an advantage during negotiations at the Hampton Roads peace conference; he also thought that he could reconcentrate his forces if Sherman changed course for Columbia.

Lucas also argues that the Confederate forces had the advantage despite being outnumbered two-to-one: they had considerable stores of food and ammunition, compared to Sherman's foraging troops.

26, which was nearly identical in its terms to the order issued for the capture of Savannah a couple of months prior:[26]General Howard will cross the Saluda and Broad rivers as near their mouths as possible, occupy Columbia, destroy the public buildings, railroad property, manufacturing and machine shops, but will spare libraries and asylums and private dwellings.Little consideration had been made by Confederate authorities for a potential evacuation.

Around 3 in the morning, engineers successfully shot a pontoon line across the river and the army ferried two boats of sharpshooters to the far side to establish a beachhead.

He commanded the remaining troops to withdraw from Columbia, and ordered Maj. Gen. Matthew Butler to burn the Charlotte and South Carolina Rail Road terminal.

Stone was outraged at the violation of the surrender, and at the Mayor and the Aldermen, and put them under armed guard, ordering them to be shot if a single Union soldier was hurt by the Confederates.

[40] At this point, the citizens of Columbia began offering alcoholic beverages they had stolen to the Union troops in an ill-thought out attempt to placate their conquerors.

[45] By nightfall, almost the entire right wing of the Union army had entered Columbia and setup headquarters at various points in town.

[47] Maj. Gen. Howard assumed command of the Provost Guard when he entered the city, which was an unusual move, but one ordered by Sherman seemingly with an eye towards discipline.

But when he returned at 1:30 with Sherman and discovered intoxication spreading through the ranks, he ordered the Provost Guard to put drunken soldiers under temporary arrest.

Gen. John E. Smith, 3rd Brigade, XV Corps, noting the free availability of alcohol, instead ordered his troops confined to camp rather than let them fraternize in the city.

He ordered Col. Stone's troops rotated out of the Provost Guard, an action- historian Lucas considers drastic, and notes this was unprecedented in the Georgia and South Carolina campaigns.

The remainder were variously employed as spotters (and spark stoppers) atop buildings, in bucketing water, and in manning the limited number of fire engines.

[63] Several Confederate accounts describe rioters (not necessarily soldiers) intentionally burning buildings, including the Reverend Porter who in 1882 wrote that he had seen men enter houses, using cotton balls dipped in turpentine to set fires.

Mayor Goodwyn, on Howard's advice, suggested that destitute residents flee to the countryside for sustenance as soon as possible, as it would be some time before the town could be rebuilt.

[74] Looking towards the long-term security of Columbia, given that the army would be leaving soon and could not spare men to garrison the city, Howard also provided 100 rifles to the Mayor on the condition that they would not be used against the Union.

The destruction included the railroads and their engines, amounting to 55 miles destroyed or damaged; the treasury printing factory; the powder mill; the Confederate armory and arsenal; the gasworks; the foundry; the medical laboratory; and all cotton which had not burned during the inferno.

Sherman shot back on April 4, in his official report on the Carolinas Campaign, accusing Hampton of the city's destruction—through his negligence of allowing so much cotton to be placed in the streets.

"[86] James W. Loewen researched the topic for his book, Lies Across America, and found that most likely, the cotton bale fires spread and caused most of the destruction.

Lucas summarizes the Confederate perspective: "Fed by years of propaganda and a firm belief in the superiority of Southern civilization—and convinced that only a supermonstrous army could defeat their gallant sons and husbands—Southerners also tended to exaggerate the destructiveness of the Union forces.

He finds that less of the city was destroyed than claimed by contemporary accounts, and that the Union made considerable efforts to fight the fires and help residents in its aftermath.

While the exact extent of the damage may never be known, without question the fires razed political, military, and transportation targets while indiscriminately destroying commercial, educational, religious and private properties in the process.