Capture of New Orleans

Because it was founded by the French and controlled by Spain for a time, New Orleans had a population who were mostly Catholic and had created a more cosmopolitan culture than in some of the Protestant-dominated states of the British colonies.

At the time of the Civil War, much of the population was made up of French-speaking Creoles, refugees from Saint Domingue and the Haitian Revolution, enslaved and free Blacks of African and mixed descent, and recent Irish and German immigrants.

[5]: 10–11, 214 Before the steamboat, keelboat men bringing cargo downriver would break up their boats for lumber in New Orleans and travel overland back to Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, or Illinois to repeat the process.

Steamboats had enough power to move upstream against the strong current of the Mississippi, making two-way trade possible between New Orleans and the cities in the interior river network of the Upper South and Midwest.

The victory of Abraham Lincoln, the Republican presidential candidate, in the election of 1860, resulted in the secession crisis and was a catalyst to the American Civil War.

By 1860, New Orleans was one of the greatest ports in the world, with 33 different steamship lines and trade worth 500 million dollars passing through the city.

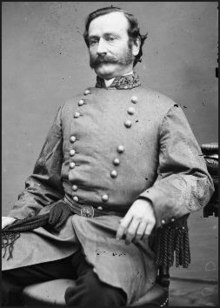

[8][9]: 41 [10]: 353 The election of Lincoln in 1860 inspired governor Thomas Overton Moore to interdict an effort to make New Orleans a “free city”, or neutral area in the conflict.

The outbreak of hostilities in the area of Fort Sumter, South Carolina, led to the story of New Orleans in the Civil War.

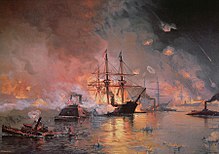

[11] The Union's strategy was devised by Winfield Scott, whose "Anaconda Plan" called for the division of the Confederacy by seizing control of the Mississippi River.

After the blockade was established, a Confederate naval counterattack attempted to drive off the Union navy, resulting in the Battle of the Head of Passes.

Once this defense was breached, only three thousand militiamen with sundry military supplies and armed with shotguns remained to face Union troops and warships.

[13] Lovell loaded his troops and supplies aboard the New Orleans, Jackson, and Great Northern railroad and sent them to Camp Moore, 78 miles (126 km) north.

Surrounded by a fragile network of levees and lower in elevation than the river around it, New Orleans was extremely vulnerable to flooding, bombardment, and insurrection.

Defense of the city against attacks from Confederate forces depended on an extensive outer ring of fortifications requiring a garrison of thousands of troops.

As a conquered territory, Louisiana had a potential for becoming a serious logistical drain on Union forces, and an unsustainable front if contested by well-organized resistance movements.

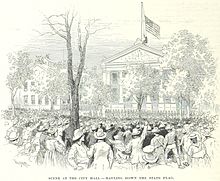

The impression had been created by Confederate officials and sympathizers[19] that New Orleans and Louisiana were held by brute military force and terror.

Butler stated, "We were 2,500 men in a city... of 150,000 inhabitants, all hostile, bitter, defiant, explosive, standing literally in a magazine, a spark only needed for destruction."

He was heavily criticized both domestically and overseas, which was a problem as the Union sought to avoid European intervention in the war on the behalf of the Confederacy.

"[24] The British House of Lords called it a "most heinous proclamation" and regarded it as "one of the grossest, most brutal, and must unmanly insults to every woman in New Orleans."

"[25] The Saturday Review criticized Butler's rule, accusing him of "gratifying his own revenge" and likening him to an uncivilized dictator: If he had possessed any of the honourable feeling which is usually associated with a soldier's profession, he would not have made war on women.

[27] But many thought the language of the order was too ambiguous and feared that Union troops would treat New Orleans women like prostitutes in regards to soliciting them for sex and perhaps even rape.

[28] Butler's inflammatory order was so controversial that it caused a significant public relations problem for the Union and he was withdrawn from New Orleans in December 1862, just eight months after taking command of the city.

He also issued Order Number 25, which distributed captured Confederate food supplies of beef and sugar in the city to the poor and starving.

This policy helped free the city from the anticipated summer yellow fever epidemic, possibly saving thousands of lives.

The rebelling laborers armed themselves with guns and newspapers[clarification needed], and fought to the death any attempts to infringe upon their newfound freedom.

Many of his acts gave great offense, such as the seizure of $800,000 that had been deposited in the office of the Dutch consul and his imprisonment of the French champagne magnate Charles Heidsieck.

The order provoked protests both in the North, the South and abroad, particularly in Britain and France, and many considered it the cause of his removal from command of the Department of the Gulf on December 17, 1862.

Those new considerations reinforced the idea by Secretary of State William H. Seward, one of Butler's political opponents, that an invasion of Texas would be favorably received by a pro-union group of German American cotton farmers living there.

Banks undertook the siege of Port Hudson and, after its successful conclusion, began the Red River Campaign in pursuit of Texan cotton.

The Red River expedition proved to be a costly failure and resulted in more wanton destruction and looting than the Butler occupation.