Car dependency

For instance, pedestrians, signalized crossings, traffic lights, cyclists, and various forms of street-based public transit, such as trams.

Automobile dependency is seen primarily as an issue of environmental sustainability due to the consumption of non-renewable resources and the production of greenhouse gases responsible for global warming.

[4] Administrators and engineers in the interwar period spent their resources making small adjustments to accommodate traffic such as widening lanes and adding parking spaces, as opposed to larger projects that would change the built environment altogether.

In the United States, the expansive manufacturing infrastructure, increase in consumerism, and the establishment of the Interstate Highway System set forth the conditions for car dependence in communities.

Zoning was created as a means of organizing specific land uses in a city so as to avoid potentially harmful adjacencies like heavy manufacturing and residential districts, which were common in large urban areas in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

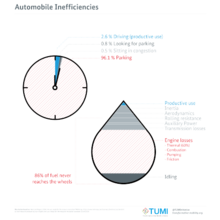

[8] This prevalence in parking has perpetuated a loss in competition between other forms of transportation such that driving becomes the de facto choice for many people even when alternatives do exist.

The design of city roads can contribute significantly to the perceived and actual need to use a car over other modes of transportation in daily life.

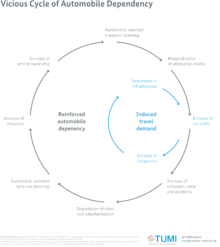

Frequently these two forces overlap in a compounding effect to induce more car dependence in an area that would have potential for a more heterogenous mix of transportation options.

[10][11] There are a number of planning and design approaches to redressing automobile dependency,[12] known variously as New Urbanism, transit-oriented development, and smart growth.

[13] There are, of course, many who argue against a number of the details within any of the complex arguments related to this topic, particularly relationships between urban density and transit viability, or the nature of viable alternatives to automobiles that provide the same degree of flexibility and speed.

There is also research into the future of automobility itself in terms of shared usage, size reduction, road-space management and more sustainable fuel sources.

Whether smart growth does or can reduce problems of automobile dependency associated with urban sprawl has been fiercely contested for several decades.

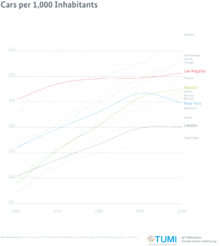

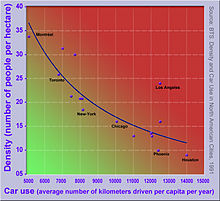

The influential study in 1989 by Peter Newman and Jeff Kenworthy compared 32 cities across North America, Australia, Europe and Asia.

Planning policies that increase population densities in urban areas do tend to reduce car use, but the effect is weak.

At the level of the neighbourhood or individual development, positive measures (like improvements to public transport) will usually be insufficient to counteract the traffic effect of increasing population density.