Carbon cycle

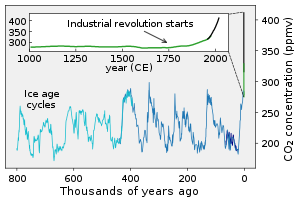

[3][7] In the far future (2 to 3 billion years), the rate at which carbon dioxide is absorbed into the soil via the carbonate–silicate cycle will likely increase due to expected changes in the sun as it ages.

[14][15][16] Once the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere falls below approximately 50 parts per million (tolerances vary among species), C3 photosynthesis will no longer be possible.

[17] Once the oceans on the Earth evaporate in about 1.1 billion years from now,[13] plate tectonics will very likely stop due to the lack of water to lubricate them.

The dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in the surface layer is exchanged rapidly with the atmosphere, maintaining equilibrium.

Partly because its concentration of DIC is about 15% higher[26] but mainly due to its larger volume, the deep ocean contains far more carbon—it is the largest pool of actively cycled carbon in the world, containing 50 times more than the atmosphere[7]—but the timescale to reach equilibrium with the atmosphere is hundreds of years: the exchange of carbon between the two layers, driven by thermohaline circulation, is slow.

The projected rate of pH reduction could slow the biological precipitation of calcium carbonates, thus decreasing the ocean's capacity to absorb CO2.

The slow or geological cycle may extend deep into the mantle and can take millions of years to complete, moving carbon through the Earth's crust between rocks, soil, ocean and atmosphere.

[2] The fast carbon cycle involves relatively short-term biogeochemical processes between the environment and living organisms in the biosphere (see diagram at start of article).

[72] During transport, part of DOC will rapidly return to the atmosphere through redox reactions, causing "carbon degassing" to occur between land-atmosphere storage layers.

[80][81][82] Most carbon incorporated in organic and inorganic biological matter is formed at the sea surface where it can then start sinking to the ocean floor.

Inorganic nutrients and carbon dioxide are fixed during photosynthesis by phytoplankton, which both release dissolved organic matter (DOM) and are consumed by herbivorous zooplankton.

These aggregates have sinking rates orders of magnitude greater than individual cells and complete their journey to the deep in a matter of days.

Over the past 2,000 years, anthropogenic activities and climate change have gradually altered the regulatory role of viruses in ecosystem carbon cycling processes.

If the process did not exist, carbon would remain in the atmosphere, where it would accumulate to extremely high levels over long periods of time.

Nonetheless, several pieces of evidence—many of which come from laboratory simulations of deep Earth conditions—have indicated mechanisms for the element's movement down into the lower mantle, as well as the forms that carbon takes at the extreme temperatures and pressures of said layer.

Not much is known about carbon circulation in the mantle, especially in the deep Earth, but many studies have attempted to augment our understanding of the element's movement and forms within the region.

[90] Thus, the investigation's findings indicate that pieces of basaltic oceanic lithosphere act as the principle transport mechanism for carbon to Earth's deep interior.

These subducted carbonates can interact with lower mantle silicates, eventually forming super-deep diamonds like the one found.

[93] Consequently, scientists have concluded that carbonates undergo reduction as they descend into the mantle before being stabilised at depth by low oxygen fugacity environments.

To illustrate, laboratory simulations and density functional theory calculations suggest that tetrahedrally coordinated carbonates are most stable at depths approaching the core–mantle boundary.

[clarification needed] Shear (S) waves moving through the inner core travel at about fifty percent of the velocity expected for most iron-rich alloys.

[102] Furthermore, another study found that in the pressure and temperature condition of the Earth's inner core, carbon dissolved in iron and formed a stable phase with the same Fe7C3 composition—albeit with a different structure from the one previously mentioned.

[103] In summary, although the amount of carbon potentially stored in the Earth's core is not known, recent studies indicate that the presence of iron carbides can explain some of the geophysical observations.

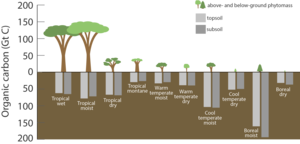

[1] Humans have also continued to shift the natural component functions of the terrestrial biosphere with changes to vegetation and other land use.

[7] Man-made (synthetic) carbon compounds have been designed and mass-manufactured that will persist for decades to millennia in air, water, and sediments as pollutants.

[25] Current trends in climate change lead to higher ocean temperatures and acidity, thus modifying marine ecosystems.

[110][107] These feedbacks are expected to weaken in the future, amplifying the effect of anthropogenic carbon emissions on climate change.

[111] The degree to which they will weaken, however, is highly uncertain, with Earth system models predicting a wide range of land and ocean carbon uptakes even under identical atmospheric concentration or emission scenarios.

[114][120][121] Nevertheless, sinks like the ocean have evolving saturation properties, and a substantial fraction (20–35%, based on coupled models) of the added carbon is projected to remain in the atmosphere for centuries to millennia.

[125] Since the invention of agriculture, humans have directly and gradually influenced the carbon cycle over century-long timescales by modifying the mixture of vegetation in the terrestrial biosphere.

The fast carbon cycle operates through the biosphere, see diagram at start of article ↑

as represented in a stylised model