Cardabiodon

Cardabiodon (/ˌkɑːrdəbaɪəˈdɒn/; meaning 'Cardabia tooth') is an extinct genus of large mackerel shark that lived about 95 to 91 million years ago (Ma) during the Cenomanian to Turonian of the Late Cretaceous.

It is a member of the Cardabiodontidae, a family unique among mackerel sharks due to differing dental structures, and contains the two species C. ricki and C. venator.

Cardabiodon was described from an associated fossil discovered in the Southern Carnarvon Basin of the Gearle Siltstone which is located within Cardabia, a cattle station in Western Australia, by paleontologist Mikael Siverson, who published his findings in 1999.

[2] In 2005, the second species C. venator was described from type specimens consisting of a total of 37 teeth recovered from a locality of the Fairport Member of the Carlile Shale near Mosby, Montana, a formation dated around 92-91 million years ago.

The original description was made in 1957 by Soviet paleontologist Leonid Glickman, where he described the taxon Pseudoisurus tomosus based on four teeth from the Saratov Oblast.

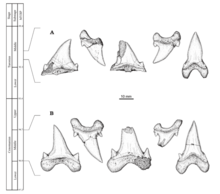

[2] Diagnostic features of Cardabiodon teeth include strongly bilabial roots, robust crowns that is either near-symmetrically erect or distally curved, visible and large tooth necks (bourlette), nonserrated cutting edges, and lateral cusplets.

C. venator teeth are slightly smaller, with the largest known tooth discovered being an anterior measuring 3.26 centimetres (1 in) in maximum slant height but are much more bulky and thicker instead.

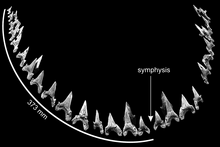

This is contrary to more generic mackerel shark dental structures where tooth size gradually decreases as it transitions from anterior to posterior (with the exception of the smaller symphysial and intermediate teeth).

To reflect the unique dental structure of Cardabiodon, Siverson erected the family Cardabiodontidae and placed the taxon, along with an extinct Cenozoic shark, Parotodus, in it.

The most notable of them includes an associated set of teeth and very large vertebrae dated in the Albian age of 105 Ma from the Toolebuc Formation in Queensland that belonged to an individual that was estimated to measure 8–9 metres (26–30 ft) in length.

[4] When compared with the ontogenetic records of Cretoxyrhina mantelli and Archaeolamna kopingensis, the vertebrae of C. ricki suggested that total length at birth was smaller than the two sharks at between 41–76 centimetres (16–30 in).

However, a growth rate slower than C. mantelli suggested an indeterminable maximum lifespan greater than 13 years, and that the ages found in the specimens were a result of premature death.

The study also found that the highest latitudinal fossils of Cardabiodon were dated just before the warmest period in the Late Cretaceous about 93 Ma known as the Cenomanian-Turonian Thermal Optimum, suggesting a shift in distribution farther north due to increasing temperatures and tropical environments.

[16] Although having lived in the colder sea temperatures of 17.5–24.2 °C (64–76 °F), Cardabiodon was contemporaneous with the Cenomanian-Turonian Thermal Optimum,[1] which led to a change in biodiversity and appearance and radiation of a new fauna like mosasaurs.

Cenomanian localities in the Western Interior Seaway have yielded several marine vertebrates that coexisted with Cardabiodon, which the shark, presumably as an apex predator, may have preyed upon.

These include many sharks including mackerel sharks like Cretodus, Cretalamna, Protolamna, and Cretoxyrhina; anacoracids like Squalicorax; and hybodonts like Ptychodus and Hybodus; large bony fish such as Protosphyraena, Pachyrhizodus, Enchodus and Xiphactinus; seabirds like Pasquiaornis and Ichthyornis; marine reptiles such as elasmosaurid and polycotylid plesiosaurs; the pliosaur Brachauchenius lucasi, protostegid sea turtles, and dolichosaurids like Coniasaurus crassidens.

[16] The Gearle Siltstone in West Australia was mainly dominated by Cretalamna, but other sharks such as Squalicorax, Archaeolamna, Paraisurus, Notorhynchus, Leptostyrax, and Carcharias were present.

[19] Like many modern sharks, Cardabiodon made use of nursery areas to give birth to and raise young, which would ideally be shallow waters that provides protection from natural predators.

An area of the Carlile Shale near Mosby, Montana, has been identified as a nursery site due to the rich prevalence of juvenile Cardabiodon fossils.

[3] Other localities in the Western Interior Seaway region of North America including the Kaskapau Formation in northwestern Alberta and the Greenhorn Limestone in central Kansas have also reported fossils of juveniles.