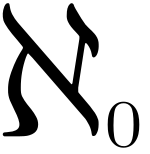

Cardinal number

(aleph) marked with subscript indicating their rank among the infinite cardinals.

In the case of finite sets, this agrees with the intuitive notion of number of elements.

If the axiom of choice is true, this transfinite sequence includes every cardinal number.

Cardinality is studied for its own sake as part of set theory.

The notion of cardinality, as now understood, was formulated by Georg Cantor, the originator of set theory, in 1874–1884.

Cantor proved that any unbounded subset of N has the same cardinality as N, even though this might appear to run contrary to intuition.

He also proved that the set of all ordered pairs of natural numbers is denumerable; this implies that the set of all rational numbers is also denumerable, since every rational can be represented by a pair of integers.

Each real algebraic number z may be encoded as a finite sequence of integers, which are the coefficients in the polynomial equation of which it is a solution, i.e. the ordered n-tuple (a0, a1, ..., an), ai ∈ Z together with a pair of rationals (b0, b1) such that z is the unique root of the polynomial with coefficients (a0, a1, ..., an) that lies in the interval (b0, b1).

In his 1874 paper "On a Property of the Collection of All Real Algebraic Numbers", Cantor proved that there exist higher-order cardinal numbers, by showing that the set of real numbers has cardinality greater than that of N. His proof used an argument with nested intervals, but in an 1891 paper, he proved the same result using his ingenious and much simpler diagonal argument.

This hypothesis is independent of the standard axioms of mathematical set theory, that is, it can neither be proved nor disproved from them.

This was shown in 1963 by Paul Cohen, complementing earlier work by Kurt Gödel in 1940.

Infinite cardinals only occur in higher-level mathematics and logic.

The intuition behind the formal definition of cardinal is the construction of a notion of the relative size or "bigness" of a set, without reference to the kind of members which it has.

In order to compare the sizes of larger sets, it is necessary to appeal to more refined notions.

This is most easily understood by an example; suppose we have the sets X = {1,2,3} and Y = {a,b,c,d}, then using this notion of size, we would observe that there is a mapping: which is injective, and hence conclude that Y has cardinality greater than or equal to X.

[2] This is called the von Neumann cardinal assignment; for this definition to make sense, it must be proved that every set has the same cardinality as some ordinal; this statement is the well-ordering principle.

It is however possible to discuss the relative cardinality of sets without explicitly assigning names to objects.

When considering these large objects, one might also want to see if the notion of counting order coincides with that of cardinal defined above for these infinite sets.

It happens that it does not; by considering the above example we can see that if some object "one greater than infinity" exists, then it must have the same cardinality as the infinite set we started out with.

In fact, for X ≠ ∅ there is an injection from the universe into [X] by mapping a set m to {m} × X, and so by the axiom of limitation of size, [X] is a proper class.

The definition does work however in type theory and in New Foundations and related systems.

Von Neumann cardinal assignment implies that the cardinal number of a finite set is the common ordinal number of all possible well-orderings of that set, and cardinal and ordinal arithmetic (addition, multiplication, power, proper subtraction) then give the same answers for finite numbers.

in cardinal arithmetic, although the von Neumann assignment puts

A possible compromise (to take advantage of the alignment in finite arithmetic while avoiding reliance on the axiom of choice and confusion in infinite arithmetic) is to apply von Neumann assignment to the cardinal numbers of finite sets (those which can be well ordered and are not equipotent to proper subsets) and to use Scott's trick for the cardinal numbers of other sets.

Formally, the order among cardinal numbers is defined as follows: |X| ≤ |Y| means that there exists an injective function from X to Y.

Assuming the axiom of choice, it can be proved that the Dedekind notions correspond to the standard ones.

Assuming the axiom of choice, multiplication of infinite cardinal numbers is also easy.

It will be unique (and equal to π) if and only if μ < π. Exponentiation is given by where XY is the set of all functions from Y to X.

Logarithms of infinite cardinals are useful in some fields of mathematics, for example in the study of cardinal invariants of topological spaces, though they lack some of the properties that logarithms of positive real numbers possess.

Similarly, the generalized continuum hypothesis (GCH) states that for every infinite cardinal