Cardinality

In mathematics, cardinality describes a relationship between sets which compares their relative size.

Beginning in the late 19th century, this concept was generalized to infinite sets, which allows one to distinguish between different types of infinity, and to perform arithmetic on them.

, with a vertical bar on each side;[3] this is the same notation as absolute value, and the meaning depends on context.

A crude sense of cardinality, an awareness that groups of things or events compare with other groups by containing more, fewer, or the same number of instances, is observed in a variety of present-day animal species, suggesting an origin millions of years ago.

[4] Human expression of cardinality is seen as early as 40000 years ago, with equating the size of a group with a group of recorded notches, or a representative collection of other things, such as sticks and shells.

[5] The abstraction of cardinality as a number is evident by 3000 BCE, in Sumerian mathematics and the manipulation of numbers without reference to a specific group of things or events.

[6] From the 6th century BCE, the writings of Greek philosophers show hints of the cardinality of infinite sets.

While they considered the notion of infinity as an endless series of actions, such as adding 1 to a number repeatedly, they did not consider the size of an infinite set of numbers to be a thing.

[7] The ancient Greek notion of infinity also considered the division of things into parts repeated without limit.

In Euclid's Elements, commensurability was described as the ability to compare the length of two line segments, a and b, as a ratio, as long as there were a third segment, no matter how small, that could be laid end-to-end a whole number of times into both a and b.

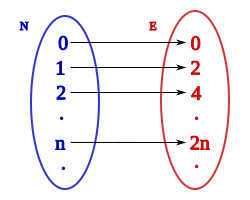

Two sets have the same cardinality if there exists a bijection (a.k.a., one-to-one correspondence) from

(see: modulo operation) is surjective, but not injective, since 0 and 1 for instance both map to 0.

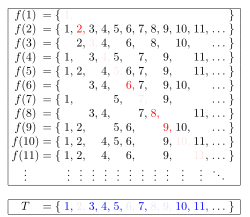

of all natural numbers has cardinality strictly less than its power set

There are two ways to define the "cardinality of a set": Assuming the axiom of choice, the cardinalities of the infinite sets are denoted For each ordinal

" (a lowercase fraktur script "c"), and is also referred to as the cardinality of the continuum.

, i.e. there is no set whose cardinality is strictly between that of the integers and that of the real numbers.

The continuum hypothesis is independent of ZFC, a standard axiomatization of set theory; that is, it is impossible to prove the continuum hypothesis or its negation from ZFC—provided that ZFC is consistent.

In the late 19th century Georg Cantor, Gottlob Frege, Richard Dedekind and others rejected the view that the whole cannot be the same size as the part.

[16][citation needed] One example of this is Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel.

Indeed, Dedekind defined an infinite set as one that can be placed into a one-to-one correspondence with a strict subset (that is, having the same size in Cantor's sense); this notion of infinity is called Dedekind infinite.

Cantor introduced the cardinal numbers, and showed—according to his bijection-based definition of size—that some infinite sets are greater than others.

One of Cantor's most important results was that the cardinality of the continuum (

(see Beth one) satisfies: The continuum hypothesis states that there is no cardinal number between the cardinality of the reals and the cardinality of the natural numbers, that is, However, this hypothesis can neither be proved nor disproved within the widely accepted ZFC axiomatic set theory, if ZFC is consistent.

These results are highly counterintuitive, because they imply that there exist proper subsets and proper supersets of an infinite set S that have the same size as S, although S contains elements that do not belong to its subsets, and the supersets of S contain elements that are not included in it.

The first of these results is apparent by considering, for instance, the tangent function, which provides a one-to-one correspondence between the interval (−½π, ½π) and R (see also Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel).

The second result was first demonstrated by Cantor in 1878, but it became more apparent in 1890, when Giuseppe Peano introduced the space-filling curves, curved lines that twist and turn enough to fill the whole of any square, or cube, or hypercube, or finite-dimensional space.

Cantor also showed that sets with cardinality strictly greater than

exist (see his generalized diagonal argument and theorem).

In this case This definition allows also obtain a cardinality of any proper class

, in particular This definition is natural since it agrees with the axiom of limitation of size which implies bijection between