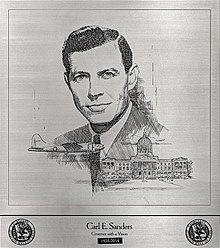

Carl Sanders

He devoted a significant amount of time to practice early on to pay off medical debt after his wife fell ill.[4] Sanders garnered an interest in politics from his father, who had served on the Richmond County Board of Commissioners.

[5] In 1958 Sanders chaired a Senate committee which investigated potential corruption in the Rural Roads Authority during Governor Marvin Griffin's tenure.

It recommended that the agency be dissolved and that future rural road projects be allocated based on population density, all financed with a pay-as-you-go system.

[6] Lieutenant Governor Ernest Vandiver became political allies with Sanders as a result of his committee work[3] and made him Senate floor leader in 1959.

[5] Vandiver became governor, and that year a federal judge ordered the Atlanta Board of Education to draft a plan to racially desegregate schools.

Only Sanders and House floor leader Frank Twitty advised desegregation, the former fearing that suspending schools "would have created a generation of illiterates.

[7] With the governor's support, Sanders was elected president pro tempore of the Senate on February 20, 1959, after Robert H. Jordan's resignation, and served in that position during the chamber's 1960 and 1962 regular sessions.

[5] Initially mulling over a potential race for the office of lieutenant governor which had a retiring incumbent, he had doubts when a similarly-named Atlanta attorney, Carl F. Sanders, declared his candidacy.

Carl E. Sanders suspected that the other man had been planted to confuse voters and spoil his chances by another candidate, Peter Zack Geer.

[5] Sanders campaigned on "a platform of progress", pledging to improve education, reorganize the State Highway Department, revamp mental health and penal institutions, recruit industry, and reapportion the General Assembly.

[14] He promised to "maintain Georgia's traditional separation"[5] but said he opposed race-baiting politics and that "I tip my hat to the past, but I take off my coat to the future.

[16] Griffin held a rally with Alabama governor-elect George Wallace, another staunch segregationist, to demonstrate his support for racial separation.

Sanders mocked this strategy at his own rally the same day, describing Griffin as "so weak in his belief in Georgia and her people that he plans to import an outsider to meddle in our affairs.

[23] By the time Sanders became governor, it was common for this official to wield wide influence over the General Assembly, including being able to essentially name the Speaker of the House and legislative committee chairmen.

When guards at the State Capitol informed Sanders that Johnson and his black pages were ignoring signs designating "white" and "colored" restrooms and water fountains, the governor had the signage removed.

Later, Johnson attempted to dine at the Commerce Club, an Atlanta venue frequented by legislators and other members of the state's political and economic elite.

[27][21] Equipped with the commission's recommendations, the following year he stated that Georgia's education system was a "modern crisis" and called for a $30 million increase in taxes to improve schools.

On February 17, 1964, the Supreme Court ruled in Wesberry v. Sanders that Georgia had to redraw its congressional districts to comply with the principle of one man, one vote.

At the Democratic State Convention in Macon on October 15, 1966, Sanders told the delegates: "A man should be loyal to his country, his family, to his God and to his political party—and don't you ever forget it.

"[33] In his speech, Sanders likened Maddox's Republican opponent, U.S. Representative Howard Callaway, to the "arrogance of Richard Nixon, the chameleon ability of Ronald Reagan to switch rather than fight, and the callous concern for human needs that is a throwback to McKinley, Harding, and Coolidge.

"[33] Callaway criticized Sanders for mishandling the state budget surplus, a position which weakened the Republican among anti-Maddox moderate voters.

[37] Early polls conducted at the behest of Carter showed most Georgians held a favorable view of Sanders' previous gubernatorial term.

Carter directed his campaign team to frame his opponent as anti-democratic, "nouveau riche", "Atlanta-oriented", overly liberal, and hostile to George Wallace.

[39] Furthermore, while his television advertisements showed him as a man of success while jogging, boating, and flying, Carter's ads focused on his farming background and suggested that Sanders was the candidate of the "big-money boys".

[41] Carter's campaign anonymously distributed a photo of Sanders getting doused with a bottle of champagne by a black Atlanta Hawks basketball player celebrating a victory at a game.

[42] The Carter campaign also published anonymous "fact-sheets" which described Sanders as a staunch ally of controversial black legislator Julian Bond (the two actually disliked one another), noted his attendance at the funeral of civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., and attacked him for denying Wallace an official visit to the state.

Sanders' workers also created another pamphlet showing a picture of dilapidated tenant housing on Carter's farm, captioned "Isn't it time someone spoke up for these people?

Sanders received 93 percent of the black vote and the support of his erstwhile backers, but Carter won overwhelmingly in rural areas.

[14] He renewed his focus on the firm—which was renamed Troutman Sanders in 1992—after his loss in the 1970 gubernatorial race and recruited Georgia Power and Southern Company as clients.