John F. Kennedy

[9][10] With Joe Sr.'s business ventures concentrated on Wall Street and Hollywood and an outbreak of polio in Massachusetts, the family decided to move from Boston to the Riverdale neighborhood of New York City in September 1927.

[24][25] In July 1938, Kennedy sailed overseas with his older brother to work at the American embassy in London, where his father was serving as President Franklin D. Roosevelt's ambassador to the Court of St.

The 59 acted as a shield from shore fire as they escaped on two rescue landing craft at the base of the Warrior River at Choiseul Island, taking ten marines aboard and delivering them to safety.

[77] According to Fredrik Logevall, Joe Sr. spent hours on the phone with reporters and editors, seeking information, trading confidences, and cajoling them into publishing puff pieces on John, ones that invariably played up his war record in the Pacific.

[88] Almost every weekend that Congress was in session, Kennedy would fly back to Massachusetts to give speeches to veteran, fraternal, and civic groups, while maintaining an index card file on individuals who might be helpful for a campaign for statewide office.

[91] Joe Sr. again financed his son's candidacy (persuading the Boston Post to switch its support to Kennedy by promising the publisher a $500,000 loan),[92] while John's younger brother Robert emerged as campaign manager.

[109][110] As a senator, Kennedy quickly won a reputation for responsiveness to requests from constituents (i.e., co-sponsoring legislation to provide federal loans to help rebuild communities damaged by the 1953 Worcester tornado), except on certain occasions when the national interest was at stake.

[111][112] In 1954, Kennedy voted in favor of the Saint Lawrence Seaway which would connect the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, despite opposition from Massachusetts politicians who argued that the project would hurt the Port of Boston economically.

[120] The hearings attracted extensive radio and television coverage where the Kennedy brothers engaged in dramatic arguments with controversial labor leaders, including Jimmy Hoffa of the Teamsters Union.

[121] It was the first major labor relations bill to pass either house since the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947 and dealt largely with the control of union abuses exposed by the McClellan Committee but did not incorporate tough Taft–Hartley amendments requested by President Eisenhower.

[134] According to Robert Caro, Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson viewed Kennedy as a "playboy", describing his performance in the Senate and the House as "pathetic" on another occasion, saying that he was "smart enough, but he doesn't like the grunt work".

[135] Author John T. Shaw acknowledges that while his Senate career is not associated with acts of "historic statesmanship" or "novel political thought," Kennedy made modest contributions as a legislator, drafting more than 300 bills to assist Massachusetts and the New England region (some of which became law).

[188] Shortly after Kennedy returned home, the Soviet Union announced its plan to sign a treaty with East Berlin, abrogating any third-party occupation rights in either sector of the city.

"[194] The Eisenhower administration had created a plan to overthrow Fidel Castro's regime though an invasion of Cuba by a counter-revolutionary insurgency composed of U.S.-trained, anti-Castro Cuban exiles[195][196] led by CIA paramilitary officers.

[214] In March 1962, Kennedy rejected Operation Northwoods, proposals for false flag attacks against American military and civilian targets,[215] and blaming them on the Cuban government to gain approval for a war against Cuba.

[217] The Kennedy administration viewed the growing Cuba-Soviet alliance with alarm, fearing that it could eventually pose a threat to the U.S.[218] On October 14, 1962, CIA U-2 spy planes took photographs of the Soviets' construction of intermediate-range ballistic missile sites in Cuba.

On October 22, after privately informing the cabinet and leading members of Congress about the situation, Kennedy announced the naval blockade on national television and warned that U.S. forces would seize "offensive weapons and associated materiel" that Soviet vessels might attempt to deliver to Cuba.

Massive land reform was not achieved; populations more than kept pace with gains in health and welfare; and according to one study, only 2 percent of economic growth in 1960s Latin America directly benefited the poor.

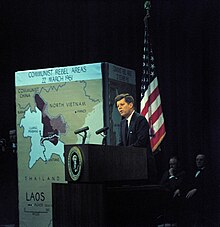

[245] Though he was unwilling to commit U.S. forces to a major military intervention in Laos, Kennedy did approve CIA activities designed to defeat Communist insurgents through bombing raids and the recruitment of the Hmong people.

[305] Kennedy's bill to increase the federal minimum wage to $1.25 an hour passed in early 1961, but an amendment inserted by conservative leader from Georgia, Carl Vinson, exempted laundry workers from the law.

[315] To the disappointment of liberals like John Kenneth Galbraith, Kennedy's embrace of the tax cut shifted his administration's focus away from the proposed old-age health insurance program and other domestic expenditures.

[325] An editorial in The New York Times praised Kennedy's actions and stated that the steel industry's price increase "imperil[ed] the economic welfare of the country by inviting a tidal wave of inflation.

In May 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality, led by James Farmer, organized integrated Freedom Rides to test a Supreme Court case ruling that declared segregation on interstate transportation illegal.

[344] As Kennedy had predicted, the day after his TV speech, and in reaction to it, House Majority leader Carl Albert called to advise him that his two-year signature effort in Congress to combat poverty in Appalachia had been defeated, primarily by the votes of Southern Democrats and Republicans.

"[346] On June 16, The New York Times published an editorial which argued that while Kennedy had initially "moved too slowly and with little evidence of deep moral commitment" in regards to civil rights he "now demonstrate[d] a genuine sense of urgency about eradicating racial discrimination from our national life.

These fears were heightened just prior to the march when FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover presented Kennedy with reports that some of King's close advisers, specifically Jack O'Dell and Stanley Levison, were communists.

[375] Full text Though Gallup polling showed that many in the public were skeptical of the necessity of the Apollo program,[376] members of Congress were strongly supportive in 1961 and approved a major increase in NASA's funding.

Travell kept a "Medicine Administration Record", cataloging Kennedy's medications: injected and ingested corticosteroids for his adrenal insufficiency; procaine shots and ultrasound treatments and hot packs for his back; Lomotil, Metamucil, paregoric, phenobarbital, testosterone, and trasentine to control his diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and weight loss; penicillin and other antibiotics for his urinary-tract infections and an abscess; and Tuinal to help him sleep.

[438] Kennedy was also reported to have had affairs with Marilyn Monroe,[439] Judith Campbell,[440] Mary Pinchot Meyer,[441] Marlene Dietrich,[30] White House intern Mimi Alford,[442] and his wife's press secretary, Pamela Turnure.

[476][477] Examples of the extensive list include: The 1963 LIFE article represented the first use of the term "Camelot" in print and is attributed with having played a major role in establishing and fixing this image of the Kennedy Administration and period in the popular mind.