Carl Zeiss

Zeiss gathered a group of gifted practical and theoretical opticians and glass makers to reshape most aspects of optical instrument production.

August moved with his parents to Buttstädt, a small regional capital north of Weimar, where he married Johanna Antoinette Friederike Schmith (1786–1856).

[5] August Zeiss then moved to Weimar, the capital of the grand duchy of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, leaving the family business in the hands of his brothers.

There he became a well respected ornamental turner, crafting lathe turned work in mother of pearl, amber, ivory, and other exotic materials.

His new master was well known beyond his local university town and his workshop is fairly well documented since he made and repaired instruments for the famous polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

He completed his apprenticeship in 1838 and departed on his journeyman years with the good wishes and recommendation of master Körner and a certificate of his studies at the university.

After long deliberation Zeiss decided to return to his original subject studied under Körner, construction of experimental scientific apparatus, and set himself up as an independent maker of precision machinery.

Zeiss returned to the well known city of Jena to renew an association with the botanist Matthias Jacob Schleiden (1804–1881) who had stimulated his original interest in optics and emphasized the need for high quality microscopes.

He referred to the increasing demand for scientific apparatus and justified his wish to work in the city with the importance of intimate association with the scientists of the university.

Zeiss was required to sit a written exam in August and finally, in November, received his "concession for the construction and sale of mechanical and optical apparatus as well as the establishment of an atelier for precision machinery in Jena."

Zeiss opened the doors of his workshop on 17 November 1846 with an initial capital investment of 100 Talers, which he had borrowed from his brother Eduard and which was later repaid by his father August.

Eyeglasses, telescopes, microscopes, drawing instruments, thermometers, barometers, balances, glassblowing accessories and other apparatuses purchased from foreign suppliers were also sold in a small shop.

Three difficult years followed with poor harvests, business crisis and revolution in the grand duchy, but by 1850, Zeiss and his microscopes had established a good enough reputation to receive an attractive offer from the University of Greifswald in Prussia.

The university's instrument maker Nobert had moved and Zeiss was asked by several members of the faculty to fill the vacancy with an appointment as curator of the physics cabinet with a salary of 200 Talers.

Microscopes produced by the apprentices which did not meet the strict standards of precision he set were destroyed on the workshop anvil personally by Zeiss.

Zeiss's efforts at improving his knowledge of precision machining and optics meant that a substantial library of books accumulated.

He advised Zeiss to concentrate his efforts on the microscope which was critical for the rapidly advancing science of cellular anatomy and very much in demand.

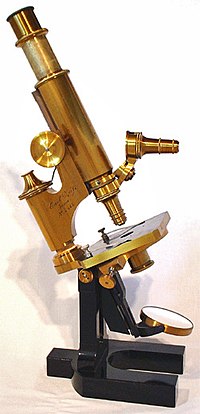

The largest of these, costing 55 Taler, was a horseshoe foot stand as made popular by the well known Parisian microscope maker Georg Oberhaeuser.

Löber had already investigated one requirement using glass reference gauges to compare the curvature of lens surfaces using the phenomenon of Newton's rings.

Most important, he added three water immersion objectives with resolution and image quality equalling anything available from Hartnack, Gundlach or other competitors.

Despite this, business remained brisk and the new objective system garnered high praise at a conference of natural scientists and physicians in Leipzig.

In recognition of his contributions Carl was awarded an honorary doctorate by the faculty of the university of Jena in 1880 at the recommendation of a long-term collaborator, the zoologist Prof. Ernst Häckel.

A move to modernization and enlargement of the firm was encouraged by Ernst Abbe, while Zeiss remained somewhat more conservative based on the many setbacks he had experienced.

Abbe discussed the problem of expanding the range of properties of optical glasses with the major producers with no success, but he continued to search for a way forward.

After demonstrating dozens of successful experiments, Zeiss used his credibility and connections to obtain financial support from the Prussian government for the efforts.

Within two years of the establishment of a glassworks in Jena, Zeiss, Abbe and Schott could offer dozens of well characterized optical glasses with repeatable composition and on large scale.

The grand duke enrolled him in the Order of the White Falcon for his 70th birthday in 1886, the same year the apochromatic objectives appeared on the market.

His critical contributions were his insistence on the greatest precision in his own work and in the products of his employees and that he maintained from the beginning close contacts with the scientists who gave him valuable insights for the design of his microscopes.

The greatest contribution of Zeiss was in his steadfast pursuit of his idea to produce microscope objectives based on theory, even when his own efforts and those of Barfuss had failed.

The production of an objective based on theoretical design was only possible with skilled artisans trained to work with the highest possible precision, upon which Zeiss had always placed the greatest emphasis.