Newton's rings

Its name derives from the mathematician and physicist Sir Isaac Newton, who studied the phenomenon in 1666 while sequestered at home in Lincolnshire in the time of the Great Plague that had shut down Trinity College, Cambridge.

At other points there is a slight air gap between the two surfaces, increasing with radial distance from the center.

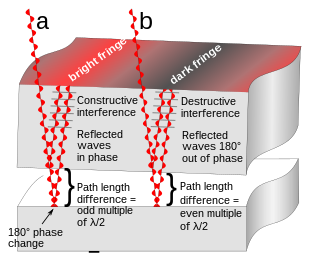

Reflection at this air-to-glass boundary causes a half-cycle (180°) phase shift because the air has a lower refractive index than the glass.

The reflected light at the lower surface returns a distance of (again) t and passes back into the lens.

When the distance 2t is zero (lens touching optical flat) the waves interfere destructively, hence the central region of the pattern is dark.

A similar analysis for illumination of the device from below instead of from above shows that in this case the central portion of the pattern is bright, not dark.

Therefore, the waves will reinforce (add) through constructive interference and the resulting reflected light intensity will be greater.

This is destructive interference: the waves will cancel (subtract) and the resulting light intensity will be weaker or zero.

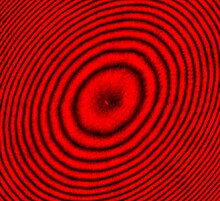

Because of the 180° phase reversal due to reflection of the bottom ray, the center where the two pieces touch is dark.

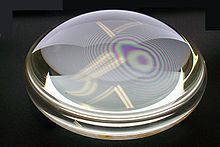

These are similar to contour lines on maps, revealing differences in the thickness of the air gap.

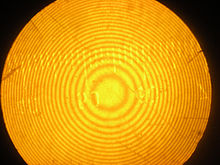

Since the gap between the glasses increases radially from the center, the interference fringes form concentric rings.

Given the radial distance of a bright ring, r, and a radius of curvature of the lens, R, the air gap between the glass surfaces, t, is given to a good approximation by

The phenomenon of Newton's rings is explained on the same basis as thin-film interference, including effects such as "rainbows" seen in thin films of oil on water or in soap bubbles.