Carolingian Renaissance

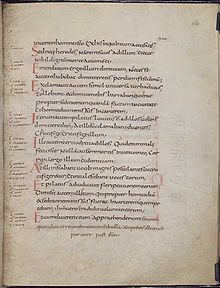

Carolingian schools were effective centers of education, and they served generations of scholars by producing editions and copies of the classics, both Christian and pagan.

Alcuin writes:[4][5][6] In the morning, at the height of my powers, I sowed the seed in Britain, now in the evening when my blood is growing cold I am still sowing in France, hoping both will grow, by the grace of God, giving some the honey of the holy scriptures, making others drunk on the old wine of ancient learningAnother prominent figure in the Carolingian renaissance was Theodulf of Orléans, a refugee from the Umayyad invasion of Spain who became involved in the cultural circle at the imperial court before Charlemagne appointed him bishop of Orléans.

Theodulf’s greatest contribution to learning was his scholarly edition of the Vulgate Bible, drawing on manuscripts from Spain, Italy, and Gaul, and even the original Hebrew.

They also applied rational ideas to social issues for the first time in centuries, providing a common language and writing style that enabled communication throughout most of Europe.

Indeed, from them emerged Martianus Capella, Cassiodorus, and Boethius, essential icons of the Roman cultural heritage in the Early Middle Ages, thanks to which the disciplines of liberal arts were preserved.

[17][18] There were numerous factors in this cultural expansion, the most obvious of which was that Charlemagne's uniting of most of Western Europe brought about peace and stability, which set the stage for prosperity.

Local economies in the West had degenerated into largely subsistence agriculture by the early 7th century, with towns functioning merely as places of gift-exchange for the elite.

[19] By the late 7th century, developed urban settlements had emerged, populated mostly by craftsmen, merchants and boaters and boasting street grids, artisanal production as well as regional and long-distance trade.

[19] The development of the Carolingian economy was fueled by the efficient organization and exploitation of labor on large estates, producing a surplus of primarily grain, wine and salt.

[19] The zenith of the early Carolingian economy was reached from 775 to 830, coinciding with the largest surpluses of the period, large-scale building of churches as well as overpopulation and three famines that showed the limits of the system.

[22] After a period of disruption from 830 to 850, caused by civil wars and Viking raids, economic development resumed in the 850s, with the emporiums disappearing completely and being replaced by fortified commercial towns.

[24][25] The slave trade enabled the West to re-engage with the Arab Muslim caliphates and the Eastern Roman Empire, so that other industries, such as textiles, were able to grow in Europe as well.

[30] The Carolingian Renaissance in retrospect also has some of the character of a false dawn, in that its cultural gains were largely dissipated within a couple of generations, a perception voiced by Walahfrid Strabo (died 849), in his introduction to Einhard's Life of Charlemagne,[n 1] summing up the generation of renewal: Charlemagne was able to offer the cultureless and, I might say, almost completely unenlightened territory of the realm which God had entrusted to him, a new enthusiasm for all human knowledge.

[29] Among those to follow Alcuin across the Channel to the Frankish court was Joseph Scottus, an Irishman who left some original biblical commentary and acrostic experiments.

Alcuin led this effort and was responsible for the writing of textbooks, creation of word lists, and establishing the trivium and quadrivium as the basis for education.

[35] The earliest concept of Europe as a distinct cultural region (instead of simply a geographic area) appeared during the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century, and included the territories which practiced Western Christianity at the time.

[37] The Carolingians produced the earliest surviving copies of the works of Cicero, Horace, Martial, Statius, Lucretius, Terence, Julius Caesar, Boethius and Martianus Capella.

As the Carolingian Reforms spread the 'proper' Latin pronunciation from France to other Romance-speaking areas, local scholars eventually felt the need to create distinct spelling systems for their own vernaculars as well, thereby initiating the literary phase of Medieval Romance.

[48] In place of the gold Roman and Byzantine solidus then common, he established a system based on a new .940-fine silver penny (Latin: denarius; French: denier) weighing 1/240 of a pound (librum, libra, or lira; livre).

Blue = realm of Pepin the Short in 758;

Orange = expansion under Charlemagne until 814;

Yellow = Marches and dependencies;

Red = Papal States .