Illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is decorated with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations.

Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers and liturgical books such as psalters and courtly literature, the practice continued into secular texts from the 13th century onward and typically include proclamations, enrolled bills, laws, charters, inventories, and deeds.

[4] Most manuscripts, illuminated or not, were written on parchment until the 2nd century BCE,[5] when a more refined material called vellum, made from stretched calf skin, was supposedly introduced by King Eumenes II of Pergamum.

This gradually became the standard for luxury illuminated manuscripts,[6] although modern scholars are often reluctant to distinguish between parchment and vellum, and the skins of various animals might be used.

Books ranged in size from ones smaller than a modern paperback, such as the pocket gospel, to very large ones such as choirbooks for choirs to sing from, and "Atlantic" bibles, requiring more than one person to lift them.

Very early printed books left spaces for red text, known as rubrics, miniature illustrations and illuminated initials, all of which would have been added later by hand.

Drawings in the margins (known as marginalia) would also allow scribes to add their own notes, diagrams, translations, and even comic flourishes.

As the production of manuscripts shifted from monasteries to the public sector during the High Middle Ages, illuminated books began to reflect secular interests.

If no scriptorium was available, then "separate little rooms were assigned to book copying; they were situated in such a way that each scribe had to himself a window open to the cloister walk.

"[15] By the 14th century, the cloisters of monks writing in the scriptorium had almost fully given way to commercial urban scriptoria, especially in Paris, Rome and the Netherlands.

The Byzantine world produced manuscripts in its own style, versions of which spread to other Orthodox and Eastern Christian areas.

[19] With their traditions of literacy uninterrupted by the Middle Ages, the Muslim world, especially on the Iberian Peninsula, was instrumental in delivering ancient classic works to the growing intellectual circles and universities of Western Europe throughout the 12th century.

Books were produced there in large numbers and on paper for the first time in Europe, and with them full treatises on the sciences, especially astrology and medicine where illumination was required to have profuse and accurate representations with the text.

[20] The tradition of illustrated manuscripts started with the Graeco-Arabic translation movement and the creation of scientific and technical treatises often based on Greek scientific knowledge, such as the Arabic versions of The Book of Fixed Stars (965 CE), De materia medica or Book of the Ten Treatises of the Eye.

The Great Mongol Shahnameh, probably from the 1330s, is a very early manuscript of one of the most common works for grand illustrated books in Persian courts.

[1] However, commercial scriptoria grew up in large cities, especially Paris, and in Italy and the Netherlands, and by the late 14th century there was a significant industry producing manuscripts, including agents who would take long-distance commissions, with details of the heraldry of the buyer and the saints of personal interest to him (for the calendar of a book of hours).

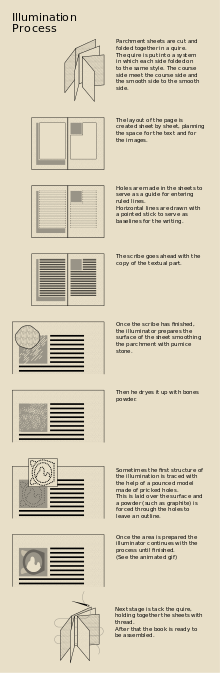

[29] The first step was to send the manuscript to a rubricator, "who added (in red or other colors) the titles, headlines, the initials of chapters and sections, the notes and so on; and then – if the book was to be illustrated – it was sent to the illuminator".

[31] To prevent such poorly made manuscripts and illuminations from occurring, a script was typically supplied first, "and blank spaces were left for the decoration.

In the Early Medieval period the text and illumination were often done by the same people, normally monks, but by the High Middle Ages the roles were typically separated, except for routine initials and flourishes, and by at least the 14th century there were secular workshops producing manuscripts, and by the beginning of the 15th century these were producing most of the best work, and were commissioned even by monasteries.

This trend intensified in the Gothic period, when most manuscripts had at least decorative flourishes in places, and a much larger proportion had images of some sort.

A Gothic page might contain several areas and types of decoration: a miniature in a frame, a historiated initial beginning a passage of text, and a border with drolleries.

From a religious perspective, "the diverse colors wherewith the book is illustrated, not unworthily represent the multiple grace of heavenly wisdom.

[37] Mineral-based colors, including: Yellow was often blended with other pigments in order to create natural earth tones, of which were common in medieval manuscript illumination.

[1][33] Black was used for inking text as well as for outlining facial features and gilded aspects like halos in order to create further depth and visual emphasis.

[30] During this time period the price of gold had become so cheap that its inclusion in an illuminated manuscript accounted for only a tenth of the cost of production.

They produced manuscripts for their own use; heavily illuminated ones tended to be reserved for liturgical use in the early period, while the monastery library held plainer texts.

[1] Especially after the book of hours became popular, wealthy individuals commissioned works as a sign of status within the community, sometimes including donor portraits or heraldry: "In a scene from the New Testament, Christ would be shown larger than an apostle, who would be bigger than a mere bystander in the picture, while the humble donor of the painting or the artist himself might appear as a tiny figure in the corner.

By the end of the Middle Ages even many religious manuscripts were produced in secular commercial workshops, such as that of William de Brailes in 13th-century Oxford, for distribution through a network of agents, and blank spaces might be reserved for the appropriate heraldry to be added locally by the buyer.

The growing genre of luxury illuminated manuscripts of secular works was very largely produced in commercial workshops, mostly in cities such as Paris, Ghent, Bruges and north Italy.

I. Charcoal powder dots create the outline II. Silverpoint drawing is sketched III. Illustration is retraced with ink IV. The surface is prepared for the application of gold leaf V. Gold leaf is laid down VI. Gold leaf is burnished to make it glossy and reflective VII. Decorative impressions are made to adhere the leaf VIII. Base colors are applied IX. Darker tones are used to give volume X. Further details are drawn XI. Lighter colors are used to add particulars XII. Ink borders are traced to finalize the illumination