Caspar David Friedrich

Friedrich's paintings often set contemplative human figures silhouetted against night skies, morning mists, barren trees or Gothic ruins.

Art historian Christopher John Murray described their presence, in diminished perspective, amid expansive landscapes, as reducing the figures to a scale that directs "the viewer's gaze towards their metaphysical dimension".

[3] As Germany moved towards modernisation in the late 19th century, a new sense of urgency characterised its art, and Friedrich's contemplative depictions of stillness came to be seen as products of a bygone age.

The rise of Nazism in the early 1930s saw a resurgence in Friedrich's popularity, but this was followed by a sharp decline as his paintings were, by association with the Nazi movement, seen as promoting German nationalism.

[note 1] The sixth of ten children, he was raised in the strict Lutheran creed of his father Adolf Gottlieb Friedrich, a candle-maker and soap boiler.

Four years later Friedrich entered the prestigious Academy of Copenhagen, where he began his education by making copies of casts from antique sculptures before proceeding to drawing from life.

These artists were inspired by the Sturm und Drang movement and represented a midpoint between the dramatic intensity and expressive manner of the budding Romantic aesthetic and the waning neo-classical ideal.

He executed his studies almost exclusively in pencil, even providing topographical information, yet the subtle atmospheric effects characteristic of Friedrich's mid-period paintings were rendered from memory.

[18] These effects took their strength from the depiction of light, and of the illumination of sun and moon on clouds and water: optical phenomena peculiar to the Baltic coast that had never before been painted with such an emphasis.

The poor quality of the entries began to prove damaging to Goethe's reputation, so when Friedrich entered two sepia drawings—Procession at Dawn and Fisher-Folk by the Sea—the poet responded enthusiastically and wrote, "We must praise the artist's resourcefulness in this picture fairly.

The artist's friends publicly defended the work, while art critic Basilius von Ramdohr published a long article challenging Friedrich's use of landscape in a religious context.

Nevertheless, with the aid of his Dresden-based friend Graf Vitzthum von Eckstädt, Friedrich attained citizenship, and in 1818, membership in the Saxon Academy with a yearly dividend of 150 thalers.

[27] Although he had hoped to receive a full professorship, it was never awarded him as, according to the German Library of Information, "it was felt that his painting was too personal, his point of view too individual to serve as a fruitful example to students.

"[28] Politics too may have played a role in stalling his career: Friedrich's decidedly Germanic subjects and costuming frequently clashed with the era's prevailing pro-French attitudes.

Physiologist and painter Carl Gustav Carus notes in his biographical essays that marriage did not impact significantly on either Friedrich's life or personality, yet his canvasses from this period, including Chalk Cliffs on Rügen—painted after his honeymoon—display a new sense of levity, while his palette is brighter and less austere.

In 1820, the Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich, at the behest of his wife Alexandra Feodorovna, visited Friedrich's studio and returned to Saint Petersburg with a number of his paintings, an exchange that began a patronage that continued for many years.

[33] Not long thereafter, the poet Vasily Zhukovsky, tutor to the Grand Duke's son (later Tsar Alexander II), met Friedrich in 1821 and found in him a kindred spirit.

Though death finds symbolic expression in boats that move away from shore—a Charon-like motif—and in the poplar tree, it is referenced more directly in paintings like The Abbey in the Oakwood (1808–1810), in which monks carry a coffin past an open grave, toward a cross, and through the portal of a church in ruins.

[55] Countering the sense of despair are Friedrich's symbols for redemption: the cross and the clearing sky promise eternal life, and the slender moon suggests hope and the growing closeness of Christ.

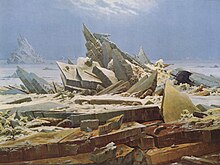

Completed in 1824, it depicted a grim subject, a shipwreck in the Arctic Ocean; "the image he produced, with its grinding slabs of travertine-colored floe ice chewing up a wooden ship, goes beyond documentary into allegory: the frail bark of human aspiration crushed by the world's immense and glacial indifference.

"[59] Friedrich's written commentary on aesthetics was limited to a collection of aphorisms set down in 1830, in which he explained the need for the artist to match natural observation with an introspective scrutiny of his own personality.

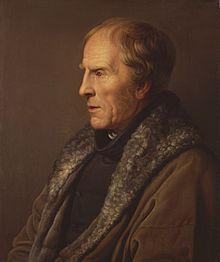

[61] Art historians and some of his contemporaries attribute such interpretations to the losses suffered during his youth to the bleak outlook of his adulthood,[62] while Friedrich's pale and withdrawn appearance helped reinforce the popular notion of the "taciturn man from the North".

[note 5] Moved by the deaths of three friends killed in battle against France, as well as by Kleist's 1808 drama Die Hermannsschlacht, Friedrich undertook a number of paintings in which he intended to convey political symbols solely by means of the landscape—a first in the history of art.

[17] In 1934, the Belgian painter René Magritte (1898–1967) paid tribute in his work The Human Condition, which directly echoes motifs from Friedrich's art in its questioning of perception and the role of the viewer.

[71] A few years later, the Surrealist journal Minotaure included Friedrich in a 1939 article by the critic Marie Landsberger, thereby exposing his work to a far wider circle of artists.

Rosenblum specifically describes Friedrich's 1809 painting The Monk by the Sea, Turner's The Evening Star[80] and Rothko's 1954 Light, Earth and Blue[81] as revealing affinities of vision and feeling.

In the abstract language of Rothko, such literal detail—a bridge of empathy between the real spectator and the presentation of a transcendental landscape—is no longer necessary; we ourselves are the monk before the sea, standing silently and contemplatively before these huge and soundless pictures as if we were looking at a sunset or a moonlit night.

[86] Friedrich's reputation suffered further damage when his imagery was adopted by a number of Hollywood directors, including Walt Disney, built on the work of such German cinema masters as Fritz Lang and F. W. Murnau, within the horror and fantasy genres.

[87] His rehabilitation was slow, but enhanced through the writings of such critics and scholars as Werner Hofmann, Helmut Börsch-Supan and Sigrid Hinz, who successfully rebutted the political associations ascribed to his work, developed a catalogue raisonné, and placed Friedrich within a purely art-historical context.

[91] In line with the Romantic ideals of his time, he intended his paintings to function as pure aesthetic statements, so he was cautious that the titles given to his work were not overly descriptive or evocative.