Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

Historians and archaeologists continue to develop our understanding of British castles, while vigorous academic debates in recent years have questioned the interpretation of physical and documentary material surrounding their original construction and use.

A lack of archaeological evidence for timber buildings has tended to disguise the extent of castle-building throughout Europe prior to 1066,[3] and many of the early wooden castles were built on the site of earlier fortifications.

[7] Rural burhs were smaller and usually consisted of a wooden hall with a wall enclosing various domestic buildings along with an entrance tower called a burh-geat, which was apparently used for ceremonial purposes.

[14] This royal castle programme focused on controlling the towns and cities of England and the associated lines of communication, including Cambridge, Huntingdon, Lincoln, Norwich, Nottingham, Wallingford, Warwick and York.

In a few key locations the king gave his followers compact groups of estates including the six rapes of Sussex and the three earldoms of Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford; intended to protect the line of communication with Normandy and the Welsh border respectively.

[22] As a result, castle building by the Norman nobility across England and the Marches lacked a grand strategic plan, reflecting local circumstances such as military factors and the layout of existing estates and church lands.

[36] Chepstow too was heavily influenced by Romanesque design, reusing numerous materials from the nearby Venta Silurum to produce what historian Robert Liddiard has termed "a play upon images from Antiquity".

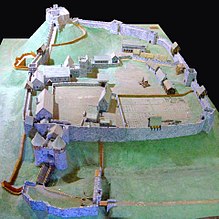

[39] While motte-and-bailey and ring-work castles took great effort to build, they required relatively few skilled craftsmen allowing them to be raised using forced labour from the local estates; this, in addition to the speed with which they could be built – a single season, made them particularly attractive immediately after the conquest.

[54] Similarly there has been extensive debate over the role of Orford Castle whose expensive, three-cornered design most closely echoes imperial Byzantine palaces and may have been intended by Henry II to be more symbolic than military in nature.

[70] In the 12th century the practice of castle-guards emerged in England and Wales, under which lands were assigned to local lords on condition that the recipient provided a certain number of knights or sergeants for the defence of a named castle.

[118] In addition to having fewer or no dead zones, and being easier to defend against mining, these castle designs were also much less easy to attack with trebuchets as the curved surfaces could deflect some of the force of the shot.

[121] In England, crossbows were primarily made at the Tower of London but St Briavels Castle, with the local Forest of Dean available to provide raw materials, became the national centre for quarrel manufacture.

[147] The later native Welsh castles, built in the 1260s, more closely resemble Norman designs; including round towers and, in the case of Criccieth and Dinas Brân, twin-towered gatehouse defences.

[148] Historian Richard Morris has suggested that "the impression is firmly given of an elite group of men-of-war, long-standing comrades in arms of the king, indulging in an orgy of military architectural expression on an almost unlimited budget".

For example, Caernarvon was decorated with carved eagles, equipped with polygonal towers and expensive banded masonry, all designed to imitate the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, then the idealised image of imperial power.

[158] In the middle of the 13th century Henry III began to redesign his favourite castles, including Winchester and Windsor, building larger halls, grander chapels, installing glass windows and decorating the palaces with painted walls and furniture.

[170] In the north of England improvements in the security of the Scottish border, and the rise of major noble families such as the Percies and the Nevilles, encouraged a surge in castle building at the end of the 14th century.

[182] Carisbrooke, Corfe, Dover, Portchester, Saltwood and Southampton Castle received cannon during the late 14th century, small circular "keyhole" gunports being built in the walls to accommodate the new weapons.

[194] North of the border the construction of Holyrood Great Tower between 1528 and 1532 picked up on this English tradition, but incorporated additional French influences to produce a highly secure but comfortable castle, guarded by a gun park.

[218] In Scotland James IV's forfeiture of the Lordship of the Isles in 1494 led to an immediate burst of castle building across the region and, over the longer term, an increased degree of clan warfare, while the subsequent wars with England in the 1540s added to the level of insecurity over the rest of the century.

[219] Irish tower houses were built from the end of the 14th century onward as the countryside disintegrated into the unstable control of a large number of small lordships and Henry VI promoted their construction with financial rewards in a bid to improve security.

[246] Those maintained as private homes; such as Arundel, Berkeley, Carlisle and Winchester were in much better condition, but not necessarily defendable in a conflict; while some such as Bolsover were redesigned as more modern dwellings in a Palladian style.

As historian Simon Thurley has described, the shifting "functional requirements, patterns of movement, modes of transport, aesthetic taste and standards of comfort" amongst royal circles were also changing the qualities being sought in a successful castle.

[282] Many castles remained in use as county gaols, run by gaolers as effectively private businesses; frequently this involved the gatehouse being maintained as the main prison building, as at Cambridge, Bridgnorth, Lancaster, Newcastle and St Briavels.

[296] Paintings in this style usually portrayed castles as indistinct, faintly coloured objects in the distance; in writing, the picturesque account eschewed detail in favour of bold first impressions on the sense.

[318] A similar trend can be seen at Rothesay where William Burges renovated the older castle to produce a more "authentic" design, heavily influenced by the work of the French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.

In some cases this had destructive consequences as wealthy collectors bought and removed architectural features and other historical artefacts from castles for their own collections, a practice that produced significant official concern.

[360] The study of British castles remained primarily focused on analysing their military role, however, drawing on the evolutionary model of improvements suggested by Thompson earlier in the century.

[362] As historian Robert Liddiard has described it, the older paradigm of "Norman militarism" as the driving force behind the formation of Britain's castles was replaced by a model of "peaceable power".

[363] The next twenty years was characterised by an increasing number of major publications on castle studies, examining the social and political aspects of the fortifications, as well as their role in the historical landscape.