The Anarchy

[5] In 1120, the political landscape changed dramatically when the White Ship sank en route from Barfleur in Normandy to England; around three hundred passengers died, including Adelin.

[30] On 15 December, Henry delivered an agreement under which Stephen would grant extensive freedoms and liberties to the church, in exchange for the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Papal Legate supporting his succession to the throne.

[26] Theobald met with the Norman barons and Robert of Gloucester at Lisieux on 21 December but their discussions were interrupted by the sudden news from England that Stephen's coronation was to occur the next day.

Seen positively, Stephen stabilised the northern border with Scotland, contained Geoffrey's attacks on Normandy, was at peace with Louis VI, enjoyed good relations with the church and had the broad support of his barons.

[69] Stephen himself went west in an attempt to regain control of Gloucestershire, first striking north into the Welsh Marches, taking Hereford and Shrewsbury, then heading south to Bath.

[69] The powerful Ranulf, Earl of Chester, considered himself to hold the traditional rights to Carlisle and Cumberland and was extremely displeased to see them being given to the Scots, a problem which would have long lasting implications in the war.

Stephen created many more, filling them with men he considered to be loyal, capable military commanders, and in the more vulnerable parts of the country assigning them new lands and additional executive powers.

[76][nb 7] Stephen appears to have had several objectives in mind, including both ensuring the loyalty of his key supporters by granting them these honours, and improving his defences in vulnerable parts of the kingdom.

[80] These bishops were powerful landowners as well as ecclesiastical rulers, and they had begun to build new castles and increase the size of their military forces, leading Stephen to suspect that they were about to defect to the Empress Matilda.

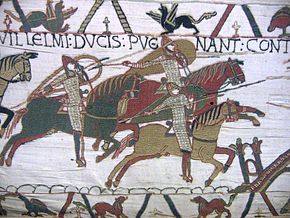

Anglo-Norman warfare during the civil war was characterised by attritional military campaigns, in which commanders tried to raid enemy lands and seize castles in order to allow them to take control of their adversaries' territory, ultimately winning slow, strategic victories.

[94] Similarly, Stephen built a new chain of fen-edge castles at Burwell, Lidgate, Rampton, Caxton, and Swavesey – each about six to nine miles (ten to fifteen km) apart – in order to protect his lands around Cambridge.

[108] Matilda was less popular with contemporary chroniclers than Stephen; in many ways she took after her father, being prepared to loudly demand compliance of her court, when necessary issuing threats and generally appearing arrogant.

[115][nb 10] Matilda stayed at Arundel Castle, whilst Robert marched north-west to Wallingford and Bristol, hoping to raise support for the rebellion and to link up with Miles of Gloucester, who took the opportunity to renounce his fealty to the king.

[120][nb 11] Although there had been few new defections to the Empress, Matilda now controlled a compact block of territory stretching out from Gloucester and Bristol south-west into Devon and Cornwall, west into the Welsh Marches and east as far as Oxford and Wallingford, threatening London.

[130] In an effort to negotiate a truce, Henry of Blois held a peace conference at Bath, at which Robert represented the Empress, and Queen Matilda and Archbishop Theobald the King.

[134] Stephen returned to London but received news that Ranulf, his brother and their family were relaxing in Lincoln Castle with a minimal guard force, a ripe target for a surprise attack of his own.

[136] Robert and Ranulf's forces had superiority in cavalry and Stephen dismounted many of his own knights to form a solid infantry block; he joined them himself, fighting on foot in the battle.

[140][nb 13] Robert took Stephen back to Gloucester, where the king met with the Empress Matilda, and was then moved to Bristol Castle, traditionally used for holding high-status prisoners.

[149] Despite securing the support of Geoffrey de Mandeville, who controlled the Tower of London, forces loyal to Stephen and Queen Matilda remained close to the city and the citizens were fearful about welcoming the Empress.

[150] On 24 June, shortly before the planned coronation, the city rose up against the Empress and Geoffrey de Mandeville; Matilda and her followers only just fled in time, making a chaotic retreat to Oxford.

[157] Henry's alliance with the Empress proved short-lived, as they soon fell out over political patronage and ecclesiastical policy; the bishop met Stephen's wife Queen Matilda at Guildford and transferred his support to her.

[166] Possibly this illness was the result of his imprisonment the previous year, but he finally recovered and travelled north to raise new forces and to successfully convince Ranulf of Chester to change sides once again.

[180] In the west, Robert of Gloucester and his followers continued to raid the surrounding royalist territories, and Wallingford Castle remained a secure Angevin stronghold, too close to London for comfort.

[186] The character of the conflict in England gradually began to shift; as historian Frank Barlow suggests, by the late 1140s "the civil war was over", barring the occasional outbreak of fighting.

[187] In 1147 Robert of Gloucester died peacefully, and the next year the Empress Matilda defused an argument with the Church over the ownership of Devizes Castle by returning to Normandy, contributing to reducing the tempo of the war.

[206] In the face of the increasingly wintry weather, Stephen agreed to a temporary truce and returned to London, leaving Henry to travel north through the Midlands where the powerful Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, announced his support for the Angevin cause.

[208] Many of the details of their discussions are unclear, but it appears that the churchmen emphasised that while they supported Stephen as king, they sought a negotiated peace; Henry reaffirmed that he would avoid the English cathedrals and would not expect the bishops to attend his court.

Stephen lost the towns of Oxford and Stamford to Henry while the king was diverted fighting Hugh Bigod in the east of England, but Nottingham Castle survived an Angevin attempt to capture it.

[232] Some parts of the country, though, were barely touched by the conflict—for example, Stephen's lands in the south-east and the Angevin heartlands around Gloucester and Bristol were largely unaffected, and David I ruled his territories in the north of England effectively.

The king of Scotland and local Welsh rulers had taken advantage of the long civil war in England to seize disputed lands; Henry set about reversing this trend.