Castra

This is not any land but is a prepared or cultivated tract, such as a farm enclosed by a fence or a wooden or stone wall of some kind.

Castro, also derived from Castrum, is a common Spanish family name as well as toponym in Spain and other Hispanophone countries, Italy, and the Balkans, either by itself or in various compounds such as the World Heritage Site of Gjirokastër (earlier Argurokastro).

The terms stratopedon (army camp) and phrourion (fortification) were used by Greek language authors to translate castrum and castellum, respectively.

The most detailed description that survives about Roman military camps is De Munitionibus Castrorum, a manuscript of 11 pages that dates most probably from the late 1st to early 2nd century AD.

"… as soon as they have marched into an enemy's land, they do not begin to fight until they have walled their camp about; nor is the fence they raise rashly made, or uneven; nor do they all abide ill it, nor do those that are in it take their places at random; but if it happens that the ground is uneven, it is first levelled: their camp is also four-square by measure, and carpenters are ready, in great numbers, with their tools, to erect their buildings for them.

"[9] To this end a marching column ported the equipment needed to build and stock the camp in a baggage train of wagons and on the backs of the soldiers.

The least permanent of these were castra aestiva or aestivalia, "summer camps", in which the soldiers were housed sub pellibus or sub tentoriis, "under tents".

For the winter the soldiers retired to castra hiberna containing barracks and other buildings of more solid materials, with timber construction gradually being replaced by stone.

Previously, legions were raised for specific military campaigns and subsequently disbanded, requiring only temporary castra.

From the most ancient times Roman camps were constructed according to a certain ideal pattern, formally described in two main sources, the De Munitionibus Castrorum and the works of Polybius.

[17] Alan Richardson compares both original authors and concludes that "the Hyginian model greatly reduced the area and perimeter length for any given force.

Ideally the process started in the centre of the planned camp at the site of the headquarters tent or building (principia).

[18] Steinhoff theorizes that Richardson has identified a commonality and builds on the latter's detailed studies to suggest that North African encampments in the time of Hadrian were based on the same geometrical skill.

The base (munimentum, "fortification") was placed entirely within the vallum ("wall"), which could be constructed under the protection of the legion in battle formation if necessary.

The construction crews dug a trench (fossa), throwing the excavated material inward, to be formed into the rampart (agger).

In the latera ("sides") were the Arae (sacrificial altars), the Auguratorium (for auspices), the Tribunal, where courts martial and arbitrations were conducted (it had a raised platform), the guardhouse, the quarters of various kinds of staff and the storehouses for grain (horrea) or meat (carnarea).

The Praetentura ("stretching to the front") contained the Scamnum Legatorum, the quarters of officers who were below general but higher than company commanders (Legati).

[28] Near the Principia were the Valetudinarium (hospital), Veterinarium (for horses), Fabrica ("workshop", metals and wood), and further to the front the quarters of special forces.

One of the major considerations for selecting the site of a camp was the presence of running water, which the engineers diverted into the sanitary channels.

Drinking water came from wells; however, the larger and more permanent bases featured the aqueduct, a structure running a stream captured from high ground (sometimes miles away) into the camp.

In it were located all the resources of nature and the terrain required by the base: pastures, woodlots, water sources, stone quarries, mines, exercise fields and attached villages.

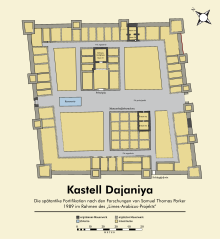

Each camp discovered by archaeology has its own specific layout and architectural features, which makes sense from a military point of view.

For defence, troops could be formed in an acies, or "battle-line", outside the gates where they could be easily resupplied and replenished as well as being supported by archery from the palisade.

Many of the towns of England still retain forms of the word castra in their names, usually as the suffixes "-caster", "-cester" or "-chester" – Lancaster, Tadcaster, Worcester, Gloucester, Mancetter, Uttoxeter, Colchester, Chester, Manchester and Ribchester for example.

Swordsmanship lessons and use of the shooting range probably took place on the campus, a "field" outside the castra, from which English "camp" derives.

However, under Antoninus Pius, citizenship was no longer granted to the children of rank-and-file veterans, the privilege becoming restricted only to officers.

[40] They became permanent members of the community and would stay on after the troops were withdrawn, as in the notable case of Saint Patrick's family.

Conducted in parallel with the ordinary activities was "the duty", the official chores required by the camp under strict military discipline.

The legate was ultimately responsible for them as he was for the entire camp, but he delegated the duty to a tribune chosen as officer of the day.

The responsibilities (curae) of the many kinds of detail were distributed to the men by all the methods considered fair and democratic: lot, rotation and negotiation.