Casus belli

The term casus belli came into widespread use in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries through the writings of Hugo Grotius (1653), Cornelius van Bynkershoek (1707), and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui (1732), among others, and due to the rise of the political doctrine of jus ad bellum or "just war theory".

[10] He pointed out that in the modern field of peace and conflict studies, scholars also frequently list causes such as "struggle for power, arms races and conflict spirals, ethnicity and nationalism, domestic political regime type and leadership change, economic interdependence and trade, territory, climate change-induced scarcity, and so on".

This section outlines a number of the more famous and/or controversial cases of casus belli which have occurred in modern times.

[13] Historian David Herbert Donald (1996) concluded that President Abraham Lincoln's "repeated efforts to avoid collision in the months between inauguration and the firing on Ft. Sumter showed he adhered to his vow not to be the first to shed fraternal blood.

[13] Watson lamented how Jefferson Davis and other Confederate leaders were 'vainglorious[ly]' celebrating the victory at Sumter, while forgetting that making the first move had given the Confederacy the immediate internationally negative reputation of being the aggressor, and had granted Seward 'the undivided sympathy of the North'.

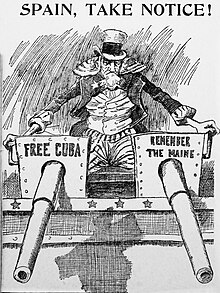

The McKinley administration did not cite the explosion as a casus belli, but others were already inclined to go to war with Spain over perceived atrocities and loss of control in Cuba.

This telegram was intercepted by the British, then relayed to the U.S., which led to President Woodrow Wilson then using it to convince Congress to join World War I alongside the Allies.

[19] In Japanese Manchuria, Japan staged the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937 as a casus belli to initiate the Second World War.

[20] In August 1939, to implement the first phase of this policy, Germany's Nazi government under Hitler's leadership staged the Gleiwitz incident, which was used as a casus belli for the invasion of Poland the following September.

[21][22] In the documentary film The Fog of War, then-US Defense Secretary Robert McNamara concedes the attack during the second incident did not happen, though he says that he and President Johnson believed it did so at the time.

The PAVN Museum in Hanoi displays "Part of a torpedo boat ... which successfully chased away the USS Maddox August 2nd, 1964".

The Israeli government had a short list of casūs belli, acts that it would consider provocations justifying armed retaliation.

[25] When the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, it cited Iraq's non-compliance with the terms of cease-fire agreement for the 1990–1991 Gulf War, as well as planning in the 1993 attempted assassination of former President George H. W. Bush and firing on coalition aircraft enforcing the no-fly zones as its stated casus belli.

Secretary of State Colin Powell addressed a plenary session of the United Nations Security Council on February 5, 2003, citing these reasons as justification for military action.

[30] The Foreign Ministry claimed that Ukraine tried to seize Crimean government buildings, citing this as a casus belli.

[31] Prior to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia recognized the separatist republics in Donetsk and Luhansk, and the alliance between them was ratified in their parliaments, thus creating a usable casus belli.

[34] On October 7, 2023, Palestinian militant groups, led by Hamas, launched a major attack into Israeli territory from the Gaza Strip.