Catena (linguistics)

[2] The catena has served as the basis for the analysis of a number of phenomena of syntax, such as idiosyncratic meaning, ellipsis mechanisms (e.g. gapping, stripping, VP-ellipsis, pseudogapping, sluicing, answer ellipsis, comparative deletion), predicate-argument structures, and discontinuities (topicalization, wh-fronting, scrambling, extraposition, etc.).

The capital letters serve to abbreviate the words: All of the distinct strings, catenae, components, and constituents in this tree are listed here:[9] Noteworthy is the fact that the tree contains 39 distinct word combinations that are not catenae, e.g. AC, BD, CE, BCE, ADF, ABEF, ABDEF, etc.

The following Venn diagram provides an overview of how the four units relate to each other: The catena concept has been present in linguistics for a few decades.

In the 1970s, the German dependency grammarian Jürgen Kunze called the unit a Teilbaum 'subtree'.

[10] In the early 1990s, the psycholinguists Martin Pickering and Guy Barry acknowledged the catena unit, calling it a dependency constituent.

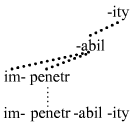

The term catena was introduced later by Timothy Osborne and colleagues as a means of avoiding confusion with the preexisting chain concept of Minimalist theory.

Numerous verb-preposition combinations are idiosyncratic collocations insofar as the choice of preposition is strongly restricted by the verb, e.g. account for, count on, fill out, rely on, take after, wait for, etc.

And also as with the particle verbs, the combinations form catenae (but not constituents) in simple declarative sentences: The verb and the preposition that it demands form a single meaning-bearing unit, whereby this unit is a catena.

The final type of collocations produced here to illustrate catenae is the complex preposition, e.g. because of, due to, inside of, in spite of, out of, outside of, etc.

The intonation pattern for these prepositions suggests that orthographic conventions are correct in writing them as two (or more) words.

It seems likely that all meaning-bearing collocations are stored as catenae in the mental lexicon of language users.

The fixed words of idioms do not bear their productive meaning, e.g. take it on the chin.

In contrast, the elided material corresponds to a non-catena in each of the unacceptable answer fragments (f–h).

An analysis of VP-ellipsis using the catena aims to capture antecedent contained deletion without quantifier raising.

Two additional complex examples further illustrate how a catena-based analysis of answer fragments works: While the elided material shown in light gray certainly cannot be construed as a constituent, it does qualify as a catena (because it forms a subtree).

The following example shows that even when the answer contains two fragments, the elided material still qualifies as a catena: Such answers that contain two (or even more) fragments are rare in English (although they are more common in other languages) and may be less than fully acceptable.

The next examples illustrate how predicates and their arguments are manifest in synonymous sentences across languages:

The next examples delivers a sense of the manner in which the main sentence predicate remains a catena as the number of auxiliary verbs increases:

When assessing the approach to predicate–argument structures in terms of catenae, it is important to keep in mind that the constituent unit of phrase structure grammar is much less helpful in characterizing the actual word combinations that qualify as predicates and their arguments.

This fact should be evident from the examples here, where the word combinations in green would not qualify as constituents in phrase structure grammars.