Dependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the constituency relation of phrase structure) and that can be traced back primarily to the work of Lucien Tesnière.

[1] Ibn Maḍāʾ, a 12th-century linguist from Córdoba, Andalusia, may have been the first grammarian to use the term dependency in the grammatical sense that we use it today.

In early modern times, the dependency concept seems to have coexisted side by side with that of phrase structure, the latter having entered Latin, French, English and other grammars from the widespread study of term logic of antiquity.

His major work Éléments de syntaxe structurale was published posthumously in 1959 – he died in 1954.

[5] DG has generated a lot of interest in Germany[6] in both theoretical syntax and language pedagogy.

In recent years, the great development surrounding dependency-based theories has come from computational linguistics and is due, in part, to the influential work that David Hays did in machine translation at the RAND Corporation in the 1950s and 1960s.

Dependency-based systems are increasingly being used to parse natural language and generate tree banks.

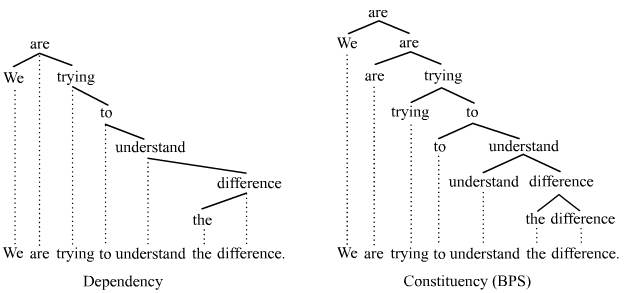

The distinction between dependency and phrase structure grammars derives in large part from the initial division of the clause.

This division is certainly present in the basic analysis of the clause that we find in the works of, for instance, Leonard Bloomfield and Noam Chomsky.

Tesnière, however, argued vehemently against this binary division, preferring instead to position the verb as the root of all clause structure.

Tesnière's stance was that the subject-predicate division stems from term logic and has no place in linguistics.

[8] The importance of this distinction is that if one acknowledges the initial subject-predicate division in syntax is real, then one is likely to go down the path of phrase structure grammar, while if one rejects this division, then one must consider the verb as the root of all structure, and so go down the path of dependency grammar.

[10] The arrow arcs in (e) are an alternative convention used to show dependencies and are favored by Word Grammar.

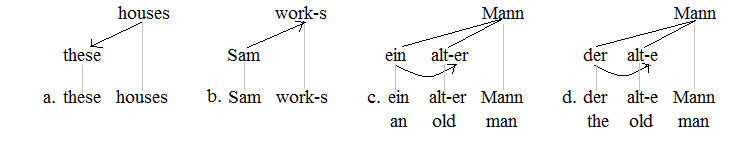

Attributive adjectives, however, are predicates that take their head noun as their argument, hence big is a predicate in tree (b) that takes bones as its one argument; the semantic dependency points up the tree and therefore runs counter to the syntactic dependency.

The type of determiner in the German examples (c) and (d) influences the inflectional suffix that appears on the adjective alt.

Consider further the following French sentences: The masculine subject le chien in (a) demands the masculine form of the predicative adjective blanc, whereas the feminine subject la maison demands the feminine form of this adjective.

The basic question about how syntactic dependencies are discerned has proven difficult to answer definitively.

One should acknowledge in this area, however, that the basic task of identifying and discerning the presence and direction of the syntactic dependencies of DGs is no easier or harder than determining the constituent groupings of phrase structure grammars.

A variety of heuristics are employed to this end, basic tests for constituents being useful tools; the syntactic dependencies assumed in the trees in this article are grouping words together in a manner that most closely matches the results of standard permutation, substitution, and ellipsis tests for constituents.

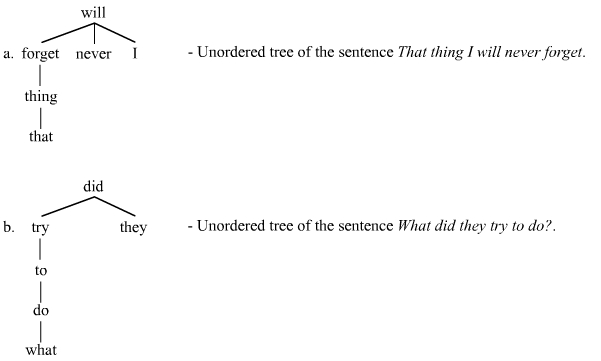

Many DGs that followed Tesnière adopted this practice, that is, they produced tree structures that reflect hierarchical order alone, e.g.

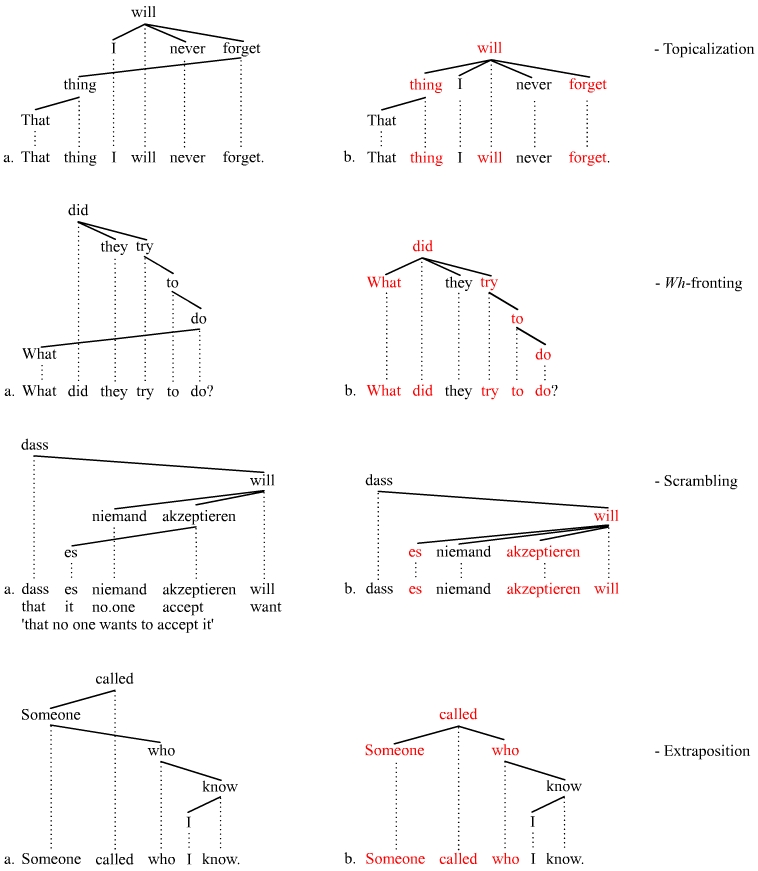

Comprehensive dependency grammar accounts of topicalization, wh-fronting, scrambling, and extraposition are mostly absent from many established DG frameworks.

This situation can be contrasted with phrase structure grammars, which have devoted tremendous effort to exploring these phenomena.

The following trees illustrate this point; they represent one way of exploring discontinuities using dependency structures.

The limitations on topicalization, wh-fronting, scrambling, and extraposition can be explored and identified by examining the nature of the catenae involved.

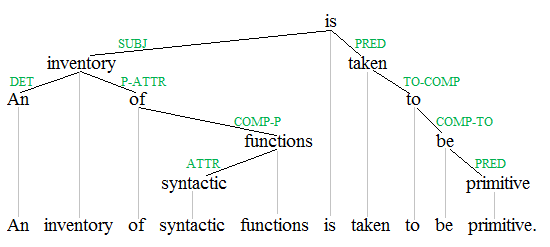

They posit an inventory of functions (e.g. subject, object, oblique, determiner, attribute, predicative, etc.).

Since DGs reject the existence of a finite VP constituent, they were never presented with the option to view the syntactic functions in this manner.

The stances of both grammar types (dependency and phrase structure) are not narrowly limited to the traditional views.