Catherine the Great

Assisted by highly successful generals such as Alexander Suvorov and Pyotr Rumyantsev, and admirals such as Samuel Greig and Fyodor Ushakov, she governed at a time when the Russian Empire was expanding rapidly by conquest and diplomacy.

The Manifesto on Freedom of the Nobility, issued during the short reign of Peter III and confirmed by Catherine, freed Russian nobles from compulsory military or state service.

The choice of Sophie as wife of the future tsar was a result of the Lopukhina affair, in which Count Jean Armand de Lestocq and King Frederick the Great of Prussia took an active part.

The objective was to strengthen the friendship between Prussia and Russia, to weaken the influence of Austria, and to overthrow the chancellor Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin, a known partisan of the Austrian alliance on whom the reigning Russian Empress Elizabeth relied.

Her hunger for fame centered on her daughter's prospects of becoming Empress of Russia, but Joanna also infuriated Elizabeth, who eventually banned her from the country for allegedly spying for King Frederick.

[28] At the time of Peter III's overthrow, other potential rivals for the throne included Ivan VI (1740–1764), who had been confined at Schlüsselburg in Lake Ladoga from the age of six months and was thought to be insane.

[29] Her coronation marks the creation of one of the main treasures of the Romanov dynasty, the Great Imperial Crown of Russia, designed by Swiss-French court diamond jeweller Jérémie Pauzié.

Inspired by Byzantine design, the crown was constructed of two half spheres, one gold and one silver, representing the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, divided by a foliate garland and fastened with a low hoop.

A shrewd statesman, Panin dedicated much effort and millions of rubles to setting up a "Northern Accord" between Russia, Prussia, Poland, and Sweden to counter the power of the Bourbon–Habsburg League.

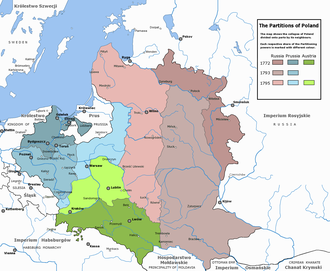

After defeating Polish loyalist forces in the Polish–Russian War of 1792 and in the Kościuszko Uprising (1794), Russia completed the partitioning of Poland, dividing all of the remaining Commonwealth territory with Prussia and Austria (1795).

[44] The Qianlong Emperor of China was committed to an expansionist policy in Central Asia and saw the Russian Empire as a potential rival, making for difficult and unfriendly relations between Beijing and Saint Petersburg.

Catherine perceived that the Qianlong Emperor was an unpleasant and arrogant neighbour, once saying: "I shall not die until I have ejected the Turks from Europe, suppressed the pride of China and established trade with India".

[47] In a 1790 letter to Baron de Grimm written in French, she called the Qianlong Emperor "mon voisin chinois aux petits yeux" ("my Chinese neighbour with small eyes").

[72] In a letter to Voltaire in 1772, she wrote: "Right now I adore English gardens, curves, gentle slopes, ponds in the form of lakes, archipelagos on dry land, and I have a profound scorn for straight lines, symmetric avenues.

[80] Catherine expressed some frustration with the economists she read for what she regarded as their impractical theories, writing in the margin of one of Necker's books that if it was possible to solve all of the state's economic problems in one day, she would have done so a long time ago.

[81] For philosophy, she liked books promoting what has been called "enlightened despotism", which she embraced as her ideal of an autocratic but reformist government that operated according to the rule of law, not the whims of the ruler, hence her interest in Blackstone's legal commentaries.

I have said that she was quite small, and yet on the days when she made her public appearances, with her head held high, her eagle-like stare and a countenance accustomed to command, all this gave her such an air of majesty that to me she might have been Queen of the World; she wore the sashes of three orders, and her costume was both simple and regal; it consisted of a muslin tunic embroidered with gold fastened by a diamond belt, and the full sleeves were folded back in the Asiatic style.

In July 1765, Dumaresq wrote to Dr. John Brown about the commission's problems and received a long reply containing very general and sweeping suggestions for education and social reforms in Russia.

However, the Moscow Foundling Home was unsuccessful, mainly due to extremely high mortality rates, which prevented many of the children from living long enough to develop into the enlightened subjects the state desired.

[97] Not long after the Moscow Foundling Home, at the instigation of her factotum, Ivan Betskoy, she wrote a manual for the education of young children, drawing from the ideas of John Locke, and founded the famous Smolny Institute in 1764, first of its kind in Russia.

Following the war and the defeat of Pugachev, Catherine laid the obligation to establish schools at the guberniya—a provincial subdivision of the Russian empire ruled by a governor—on the Boards of Social Welfare set up with the participation of elected representatives from the three free estates.

She nationalised all of the church lands to help pay for her wars, largely emptied the monasteries, and forced most of the remaining clergymen to survive as farmers or from fees for baptisms and other services.

The British ambassador to Russia, James Harris, reported back to London that: Her Majesty has a masculine force of mind, obstinacy in adhering to a plan, and intrepidity in the execution of it; but she wants the more manly virtues of deliberation, forbearance in prosperity and accuracy of judgment, while she possesses in a high degree the weaknesses vulgarly attributed to her sex—love of flattery, and its inseparable companion, vanity; an inattention to unpleasant but salutary advice; and a propensity to voluptuousness which leads to excesses that would debase a female character in any sphere of life.

In the second partition, in 1793, Russia received the most land, from west of Minsk almost to Kiev and down the river Dnieper, leaving some spaces of steppe down south in front of Ochakov, on the Black Sea.

Orlov and his other three brothers found themselves rewarded with titles, money, swords, and other gifts, but Catherine did not marry Grigory, who proved inept at politics and useless when asked for advice.

In 1780, Emperor Joseph II, the son of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa, toyed with the idea of determining whether or not to enter an alliance with Russia, and asked to meet Catherine.

She recovered well enough to begin to plan a ceremony which would establish her favourite grandson Alexander as her heir, superseding her difficult son Paul, but she died before the announcement could be made, just over two months after the engagement ball.

In his 1647 book Beschreibung der muscowitischen und persischen Reise (Description of the Muscovite and Persian journey), German scholar Adam Olearius[141] alleged a supposed Russian tendency towards bestiality with horses.

[142] Catherine's undated will, discovered in early 1792 among her papers by her secretary Alexander Vasilievich Khrapovitsky, gave specific instructions should she die: "Lay out my corpse dressed in white, with a golden crown on my head, and on it inscribe my Christian name.

According to Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun:The empress's body lay in state for six weeks in a large and magnificently decorated room in the castle, which was kept lit day and night.