Catholic bishops in Nazi Germany

[3] Ian Kershaw wrote that the churches "engaged in a bitter war of attrition with the regime, receiving the demonstrative backing of millions of churchgoers.

While the Church ultimately failed to protect its youth organisations and schools, it did have some successes in mobilizing public opinion to alter government policies.

[6] Kershaw wrote that, while the "detestation of Nazism was overwhelming within the Catholic Church", it did not preclude church leaders approving of areas of the regime's policies, particularly where Nazism "blended into 'mainstream' national aspirations"—like support for "patriotic" foreign policy or war aims, obedience to state authority (where this did not contravene divine law); and destruction of atheistic Marxism and Soviet Bolshevism - and traditional Christian anti-Judaism was "no bulwark" against Nazi biological antisemitism.

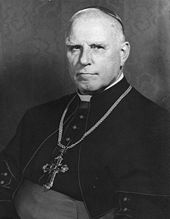

[8] By 1937, after four years of persecution, the church hierarchy, which had initially sought to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned and Pope Pius XI issued the Mit brennender Sorge anti-Nazi encyclical, which had been co-drafted by Cardinal Archbishop Michael von Faulhaber of Munich together, with Preysing and Galen and the Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Pacelli (the future Pope Pius XII).

At the close of the war, the resistor Joseph Frings, succeeded the appeaser Adolf Bertram as chairman of the Fulda Bishops' Conference, and, along with Galen and Preysing, was promoted to Cardinal by Pius XII.

[3] Thus when Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen of Münster delivered his famous 1941 denunciations of Nazi euthanasia and the lawlessness of the Gestapo, he also said that the church had never sought the overthrow of the regime.

[15] On 10 August 1940, the president of the Bishops Conference on the one hand begged Hitler to resist influences hostile to Christianity - but at the same time assured the Führer of his "loyalty to the state as it is".

Kershaw wrote that, while the "detestation of Nazism was overwhelming within the Catholic Church", it did not preclude church leaders approving of areas of the regime's policies, particularly where Nazism "blended into 'mainstream' national aspirations" - like support for "patriotic" foreign policy or war aims, obedience to state authority (where this did not contravene divine law); and destruction of atheistic Marxism and Soviet Bolshevism.

Traditional Christian anti-Judaism was "no bulwark" against Nazi biological antisemitism, wrote Kershaw, and on these issues "the churches as institutions felt on uncertain grounds".

[19] His Advent Pastoral Letters of 1942 and 1943 on the nature of human rights reflected the anti-Nazi theology of the Barmen Declaration of the Confessing Church, leading one to be broadcast in German by the BBC.

In 1944, Preysing met with and gave a blessing to Claus von Stauffenberg, in the lead up to the July Plot to assassinate Hitler, and spoke with the resistance leader on whether the need for radical change could justify tyrannicide.

He worked with American occupation forces after the war, and received the West German Republic's highest award, the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit.

Clergy, nuns and lay leaders began to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality".

[28] In March 1938, Nazi Minister of State Adolf Wagner spoke of the need to continue the fight against Political Catholicism and Alfred Rosenberg said that the churches of Germany "as they exist at present, must vanish from the life of our people".

[11] On 26 July 1941, Bishop von Galen wrote to the government to complain "The Secret Police has continued to rob the property of highly respected German men and women merely because they belonged to Catholic orders".

Catholic presses had been silenced and kindergartens closed and religious instruction in schools nearly stamped out:[45] Dear Members of the disoceses: We Bishops ... feel an ever great sorrow about the existence of powers working to dissolve the blessed union between Christ and the German people ... the existence of Christianity in Germany is at stake.The following year, on 22 March 1942, the German Bishops issued a pastoral letter on "The Struggle against Christianity and the Church":[46] The letter launched a defence of human rights and the rule of law and accused the Reich Government of "unjust oppression and hated struggle against Christianity and the Church", despite the loyalty of German Catholics to the Fatherland, and brave service of Catholics soldiers.

Repeatedly the German bishops have asked the Reich Government to discontinue this fatal struggle; but unfortunately our appeals and our endeavours were without success.The letter outlined serial breaches of the 1933 Concordat, reiterated complaints of the suffocation of Catholic schooling, presses and hospitals and said that the "Catholic faith has been restricted to such a degree that it has disappeared almost entirely from public life" and even worship within churches in Germany "is frequently restricted or oppressed", while in the conquered territories (and even in the Old Reich), churches had been "closed by force and even used for profane purposes".

The following day, the mob stoned the Cardinal's residence, broke in and ransacked it—bashing a secretary unconscious, and storming another house of the cathedral curia and throwing its curate out the window.

Archbishop Conrad Groeber of Freiburg wrote to the head of the Reich Chancellery, and offered to pay all costs being incurred by the state for the "care of mentally people intended for death".

The government refused to give a written undertaking to halt the program, and the Vatican declared on 2 December that the policy was contrary to natural and positive Divine law: "The direct killing of an innocent person because of mental or physical defects is not allowed".

Subsequent arrests of priests and seizure of Jesuit properties by the Gestapo in his home city of Munster, convinced Galen that the caution advised by his superior had become pointless.

[56] The Catholic bishops jointly expressed their "horror" at the policy in their 1942 Pastoral Letter:[47] Every man has the natural right to life and the goods essential for living.

With deep horror Christian Germans have learned that, by order of the State authorities, numerous insane persons, entrusted to asylums and institutions, were destroyed as so-called "unproductive citizens."

Nobody's life is safe unless the Commandment, "Thou shalt not kill," is observed.Under pressure from growing protests, Hitler halted the main euthanasia program on 24 August 1941, though less systematic murder of disabled people continued.

[57] While Galen survived, Bishop von Preysing's Cathedral Administrator, Fr Bernhard Lichtenberg met his demise for protesting directly to Dr Conti, the Nazi State Medical Director.

[59] According to historian Michael Phayer, "a number of bishops did want to know, and they succeeded very early on in discovering what their government was doing to the Jews in occupied Poland".

[4] Traditional Christian anti-Judaism was "no bulwark" against Nazi biological antisemitism, wrote Kershaw, and on these issues opposition was generally left to fragmented and largely individual efforts.

[38] This despite Article 4 of the reichskonkordat guaranteeing freedom of correspondence between the Vatican and the German clergy,[65] Later, in Pius XII's first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, which came only a month into the war, the Church reiterated the Catholic stance against racism and anti-semitism: "there is neither Gentile nor Jew, circumcision nor uncircumcision, barbarian nor Scythian, bond nor free.

[66] When the newly installed Nazi Government began to instigate its program of anti-semitism, Pope Pius XI, through his Secretary of State Cardinal Pacelli, ordered the Papal Nuncio in Berlin, Cesare Orsenigo, to "look into whether and how it may be possible to become involved" in their aid.

[24] Gorsky wrote that "The Vatican endeavored to find places of refuge for Jews after Kristallnacht in November 1938, and the Pope instructed local bishops to help all who were in need at the beginning of the war.