German resistance to Nazism

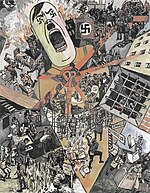

Central Europe Germany Italy Spain (Spanish Civil War) Albania Austria Baltic states Belgium Bulgaria Burma China Czechia Denmark France Germany Greece Italy Japan Jewish Luxembourg Netherlands Norway Poland Romania Slovakia Spain Soviet Union Yugoslavia Germany Italy Netherlands Portugal Spain Sweden Switzerland United Kingdom United States The German resistance to Nazism (German: Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus) included unarmed and armed opposition and disobedience to the Nazi regime by various movements, groups and individuals by various means, from attempts to assassinate Adolf Hitler or to overthrow his regime, defection to the enemies of the Third Reich and sabotage against the German Army and the apparatus of repression and attempts to organize armed struggle, to open protests, rescue of persecuted persons, dissidence and "everyday resistance".

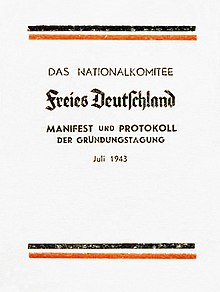

However, the relationship between the army and the civil resistance were more complex and gradually evolved: while the representatives of the workers' movement sought contacts with the army, at first, the plotters did not even question whether the public support is needed, but eventually they came, partly due to the reaction on the activities of the National Committee for a Free Germany, to a conclusion of a necessity of a democratic "people's movement" (German: Volksbewegung) which would turn the assassination into a starting point of political resistance and break the loyalty of the population to the Nazi system, although the plotters had no concrete planning or personnel consequences.

[17] In his history of the German Resistance, Peter Hoffmann wrote that "National Socialism was not simply a party like any other; with its total acceptance of criminality it was an incarnation of evil, so that all those whose minds were attuned to democracy, Christianity, freedom, humanity, or even mere legality found themselves forced into alliance.

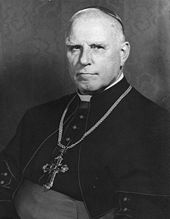

They resisted the regime's efforts to intrude on ecclesiastical autonomy but from the beginning, a minority of clergy expressed broader reservations about the new order and gradually their criticisms came to form a "coherent, systematic critique of many of the teachings of National Socialism".

For example, in a People's Court ("Volksgerichtshof") trial in Vienna, an old, seriously ill, and frail woman was sentenced to four years in prison for possessing a note she wrote found in her wallet with the rhymed text "Wir wollen einen Kaiser von Gottesgnaden und keinen Blutmörder aus Berchtesgaden.

Opposition based on this widespread dissatisfaction usually took "passive" forms—absenteeism, malingering, spreading rumours, trading on the black market, hoarding and avoiding various forms of state service such as donations to Nazi causes.

[48] Hitler and National Socialism's perceived dependence on the mass mobilization of his people, the "racial" Germans, along with the belief that Germany had lost the First World War due to an unstable home front, caused the regime to be peculiarly sensitive to public, collective protests.

Some of the earliest work on resistance examined the Catholic record, including most spectacularly local and regional protests against decrees removing crucifixes from schools, part of the regime's effort to secularize public life.

On October 11, 1943, some three hundred women protested on Adolf Hitler Square in the western German Ruhr Valley city of Witten against the official decision to withhold their food ration cards unless they evacuated their homes.

Axel von dem Bussche, member of the elite Infantry Regiment 9, volunteered to kill Hitler with hand grenades in November 1943 during a presentation of new winter uniforms, but the train containing them was destroyed by Allied bombs in Berlin, and the event had to be postponed.

This scenario, while more credible than some of the resistance's earlier plans, was based on a false premise: that the Western Allies would be willing to break with Stalin and negotiate a separate peace with a non-Nazi German government.

They organised a network of resistance cells in government offices across Germany, ready to rise and take control of their buildings when the word was given by the military that Hitler was dead.On 1 July Claus von Stauffenberg was appointed chief-of-staff to General Fromm at the Reserve Army headquarters on Bendlerstrasse in central Berlin.

The plan was for Stauffenberg to plant the briefcase with the bomb in Hitler's conference room with a timer running, excuse himself from the meeting, wait for the explosion, then fly back to Berlin and join the other plotters at the Bendlerblock.

Initially its main activities were political reeducation and indoctrination and propaganda and psychological warfare aimed at the Wehrmacht, and Seydlitz participated only in this side of the NKFD while disassociating himself from the armed struggle also conducted by the organisation, being the author and a spokesperson of pro-Soviet radio broadcasts and a parlimentaire while negotiating surrenders of the Germans.

A few hundred German POWs in the United States and Britain, some of whom had joined the Freies Deutschland movement, helped the Western Allies organize several guerrilla and counter-guerrilla bands trained for parachute deployment in the Alps.

As the Red Army stepped on German soil, the significance of the NKFD as a means to demonstrate the support of its invasion among the Germans had grown; the failure of the guerrilla warfare determined the Soviet leadership, and the Kampfgruppen became used for such activities as commando assault since these had a practical use for the Red Army as a means to harass and divert the Wehrmacht and did not require popular support at the same time, and Hitler warned about the danger of the NKFD commandos in his final address to the Ostheer on 15 April 1945.

[69] Mainly this name was used to the "traitor officers" who appeared at the front and misled the army by issuing or orally giving false orders: for example, Reich's Chancellery warned of the "Seydlitz Troops" in a circular,[70] and Hermann Fegelein wrote to Himmler that he "came to the conclusion that a significant part of the difficulties on the Eastern Front, including the collapse and elements of insubordination in a number of divisions, stem from the cunning sending to us of officers from the Seydlitz Troops and soldiers from among the prisoners of war who had been brainwashed by communists".

Most army officers, their fears of a war against the western powers apparently proven groundless, and gratified by Germany's revenge against France for the defeat of 1918, reconciled themselves to Hitler's regime, choosing to ignore its darker side.

This was a source of great frustration to the military and civil service plotters, who virtually all came from the elite and had privileged access to information, giving them a much greater appreciation of the hopelessness of Germany's situation than was possessed by the German people.

But the White Rose was not a sign of widespread civilian disaffection from the regime, and had no imitators elsewhere, although their sixth leaflet, re-titled "The Manifesto of the Students of Munich", was dropped by Allied planes in July 1943, and became widely known in World War II Germany.

The underground SPD and KPD were able to maintain their networks, and reported increasing discontent at the course of the war and at the resultant economic hardship, particularly among the industrial workers and among farmers (who suffered from the acute shortage of labour with so many young men away at the front).

In general terms, therefore, the churches were the only major organisations to offer comparatively early and open resistance: they remained so in later years.In the year following Hitler's "seizure of power", old political players looked for means to overthrow the new government.

[124][126] His speech writer Edgar Jung, a Catholic Action worker, seized the opportunity to reassert the Christian foundation of the state, pleaded for religious freedom, and rejected totalitarian aspirations in the field of religion, hoping to spur a rising, centred on Hindenburg, Papen and the army.

[144] Social worker Margarete Sommer counselled victims of racial persecution for Caritas Emergency Relief and in 1941 became director of the Welfare Office of the Berlin Diocesan Authority, under Lichtenberg, and Bishop Preysing.

In July, the Bishop of Münster, Clemens August Graf von Galen (an old aristocratic conservative, like many of the anti-Hitler army officers), publicly denounced the "euthanasia" programme in a sermon, and telegrammed his text to Hitler, calling on "the Führer to defend the people against the Gestapo."

The events of June 1934 and February 1938 do not lead one to attach much hope to energetic action by the Army against the regime"[164] Because of the failure of Germans to overthrow their Führer in 1938, the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was convinced that the resistance comprised a group of people seemingly not well organized.

[171] Goerdeler's demands for the Polish Corridor to be returned to Germany together with former colonies in Africa together with a loan to a post-Hitler government made a very poor impression with the British Foreign Office, not the least because he seemed to differ with the Nazis only in degree rather than in kind.

Just before the invasion of Poland in August 1939, General Eduard Wagner who was one of the officers involved in the abortive putsch of September 1938, wrote in a letter to his wife: "We believe we will make quick work of the Poles, and in truth, we are delighted at the prospect.

[180][150] Oster, Wilhelm Canaris and Hans von Dohnányi, backed by Beck, told Müller to ask Pius to ascertain whether the British would enter negotiations with the German opposition which wanted to overthrow Hitler.

[185] After the outbreak of World War II, the left-wing opponents of the Nazi regime, Communists, anarchist, socialists, Social Democrats, and labor union members, tried to create an anti-Nazi workers' movement by setting up resistance groups in the workplaces, spreading counter-propaganda, attempting to sabotage the armaments industry, and supporting persecuted people.