Caucasian Albania

[17] James Darmesteter, translator of the Avesta, compared Arran with Airyana Vaego[18] which he also considered to have been in the Araxes-Ararat region,[19] although modern theories tend to place this in the east of Iran.

The boundaries of Arran have shifted throughout history, sometimes encompassing the entire territory of the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan, and at other times only parts of the South Caucasus.

And he (Mashtots) inquired and examined the barbaric diction of the Albanian language, and then through his usual God-given keenness of mind invented an alphabet, which he, through the grace of Christ, successfully organized and put in order.

[43] Muslim geographers Al-Muqaddasi, Ibn-Hawqal and Estakhri recorded that a language which they called Arranian was still spoken in the capital Barda and the rest of Arran in the 10th century.

[2] It is possible that the language and literature for administration and record-keeping of the imperial chancellery for external affairs naturally became Parthian, based on the Aramaic alphabet.

[3] According to Vladimir Minorsky: "The presence of Iranian settlers in Transcaucasia, and especially in the proximity of the passes, must have played an important role in absorbing and pushing back the aboriginal inhabitants.

Such names as Sharvan, Layzan, Baylaqan, etc., suggest that the Iranian immigration proceeded chiefly from Gilan and other regions on the southern coast of the Caspian".

[48] These Islamised groups would later be known as Lezgins and Tsakhurs or mix with the Turkic and Iranian population to form present-day Azeris, whereas those that remained Christian were gradually absorbed by Armenians[49] or continued to exist on their own and be known as the Udi people.

[6] According to Robert H. Hewsen, these tribes were "certainly not of Armenian origin", and "although certain Iranian peoples must have settled here during the long period of Persian and Median rule, most of the natives were not even Indo-Europeans".

[66] The first kings of Albania were certainly the representatives of the local tribal nobility, to which attest their non-Armenian and non-Iranian names (Oroezes, Cosis and Zober in Greek sources).

The rock inscription near the south-eastern part of Boyukdash's foot (70 km from Baku) was discovered on June 2, 1948, by Azerbaijani archaeologist Ishag Jafarzadeh.

The inscription was studied by Russian expert Yevgeni Pakhomov, who assumed that the associated campaign was launched to control the Derbent Gate and that the XII Fulminata has marched out either from Melitene, its permanent base, or Armenia, where it might have moved from before.

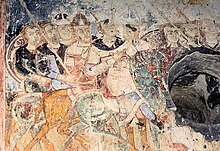

At the Battle of Avarayr, the allied forces of Caucasian Albania, Georgia, and Armenia, devoted to Christianity, suffered defeat at the hands of the Sassanid army.

[89] This new unit included: the original Caucasian Albania, found between the River Kura and the Great Caucasus; tribes living along the Caspian shore; as well as Artsakh and Utik, two territories now detached from Armenia.

Because it was more homogeneous and more developed than the original tribes to the north of the Kura, the Armenian element took over Caucasian Albania's political life and was progressively able to impose its language and culture.

[103] Khorenatsi states that "aghu" was a nickname given to Prince Arran, whom the Armenian King Vologases I (Vagharsh I) appointed as governor of northeastern provinces bordering on Armenia.

According to a legend reported by Khorenatsi, Arran was a descendant of Sisak, the ancestor of the Siunids of Armenia's province of Syunik, and thus a great-grandson of the ancestral eponym of the Armenians, the Forefather Hayk.

[104] Kaghankatvatsi and another Armenian author, Kirakos Gandzaketsi, confirm Arran's belonging to Hayk's bloodline by calling Arranshahiks "a Haykazian dynasty".

[108] As in Armenia, nobles of Aghvank are referred to by the terms nakharars (նախարար), azats (ազատ), hazarapets (հազարապետ), marzpets (մարզպետ), shinakans (շինական), etc.

[95][102] Princely families, which were later mentioned in Kaghankatvatsi's History were included in the Table of Ranks called "Gahnamak" (direct translation: "List of Thrones," Arm.

[112] After the partition, the capital city of Caucasian Albania was moved from the territories on the eastern bank of the River Kura (referred to by Armenians "Aghvank Proper," Arm.

[116] Overall, St. Mesrob made three trips to the Kingdom of Albania where he toured not only the Armenian lands of Artsakh and Utik but also territories to the north of the River Kura.

[116] Kaghankatvatsi's History describes Armenian influence on the Church of Aghvank, whose jurisdiction extended from Artsakh and Utik to regions to the north of the River Kura, in the territories of the "original", "pre-Armenian" Caucasian Albania.

[102][113] King Vachagan III helped to implant Christianity in Caucasian Albania, through a synod allowing the church legal rights in some domestic issues.

King Javanshir of Albania, the most prominent ruler of Mihranid dynasty, fought against the Arab invasion of caliph Uthman on the side of Sassanid Iran.

The history of Caucasian Albania has been a major topic of Azerbaijani revisionist theories, which came under criticism in Western and Russian academic and analytical circles, and were often characterized as "bizarre" and "futile".

[136] American author George Bournoutian gives examples of how that was done by Ziya Bunyadov, vice-chairman of Azerbaijani Academy of Sciences,[137] who earned the nickname of "Azerbaijan’s foremost Armenophobe".

When utilizing such sources, the researchers should seek out pre-Soviet editions wherever possible.According to de Waal, a disciple of Bunyadov, Farida Mammadova, has "taken the Albanian theory and used it to push Armenians out of the Caucasus altogether.

[146] Adam T. Smith, an anthropologist and associate professor of anthropology at the University of Chicago, called the removal of the khachkars "a shameful episode in humanity's relation to its past, a deplorable act on the part of the government of Azerbaijan which requires both explanation and repair".

[147] Azerbaijan instead contends that the monuments were not of Armenian, but of Caucasian Albanian, origin, which, per Thomas De Waal, did not protect "the graveyard from an act in the history wars".