Cavitation

[2][3] Non-inertial cavitation is the process in which a bubble in a fluid is forced to oscillate in size or shape due to some form of energy input, such as an acoustic field.

Since the shock waves formed by collapse of the voids are strong enough to cause significant damage to parts, cavitation is typically an undesirable phenomenon in machinery.

It may be desirable if intentionally used, for example, to sterilize contaminated surgical instruments, break down pollutants in water purification systems, emulsify tissue for cataract surgery or kidney stone lithotripsy, or homogenize fluids.

This phenomenon is coined cavitation inception and may occur behind the blade of a rapidly rotating propeller or on any surface vibrating in the liquid with sufficient amplitude and acceleration.

The bubble eventually collapses to a minute fraction of its original size, at which point the gas within dissipates into the surrounding liquid via a rather violent mechanism which releases a significant amount of energy in the form of an acoustic shock wave and as visible light.

On the other hand, a local increase in flow velocity could lead to a static pressure drop to the critical point at which cavitation could be initiated (based on Bernoulli's principle).

In a closed fluidic system where no flow leakage is detected, a decrease in cross-sectional area would lead to velocity increment and hence static pressure drop.

This is the working principle of many hydrodynamic cavitation based reactors for different applications such as water treatment, energy harvesting, heat transfer enhancement, food processing, etc.

A venturi has an inherent advantage over an orifice because of its smooth converging and diverging sections, such that it can generate a higher flow velocity at the throat for a given pressure drop across it.

[11] The cavitation phenomenon can be controlled to enhance the performance of high-speed marine vessels and projectiles, as well as in material processing technologies, in medicine, etc.

[14] Widely used in these books was the well-developed theory of conformal mappings of functions of a complex variable, allowing one to derive a large number of exact solutions of plane problems.

[17] A natural continuation of these studies was recently presented in The Hydrodynamics of Cavitating Flows[18] – an encyclopedic work encompassing all the best advances in this domain for the last three decades, and blending the classical methods of mathematical research with the modern capabilities of computer technologies.

A surface with small dunes installed on aircraft and various high speed vehicles, the total friction against the air will decrease several times.

[23] In industry, cavitation is often used to homogenize, or mix and break down, suspended particles in a colloidal liquid compound such as paint mixtures or milk.

Cavitation plays a key role in non-thermal, non-invasive fractionation of tissue for treatment of a variety of diseases[27] and can be used to open the blood-brain barrier to increase uptake of neurological drugs in the brain.

The implementation of hydrodynamic cavitation in the transesterification process allows for a significant reduction in catalyst use, quality improvement and production capacity increase.

In devices such as propellers and pumps, cavitation causes a great deal of noise, damage to components, vibrations, and a loss of efficiency.

[43] When the cavitation bubbles collapse, they force energetic liquid into very small volumes, thereby creating spots of high temperature and emitting shock waves, the latter of which are a source of noise.

[44] The pitting caused by the collapse of cavities produces great wear on components and can dramatically shorten a propeller's or pump's lifetime.

This flow velocity causes a vacuum to develop at the housing wall (similar to what occurs in a venturi), which turns the liquid into a vapor.

[47] With a double-suction pump tied to a close-coupled elbow, flow distribution to the impeller is poor and causes reliability and performance shortfalls.

This degrades overall pump performance (delivered head, flow and power consumption) and causes axial imbalance which shortens seal, bearing and impeller life.

A final problem was the effect that increased material temperature had on the relative electrochemical reactivity of the base metal and its alloying constituents.

[63] Thresher sharks use 'tail slaps' to debilitate their small fish prey and cavitation bubbles have been seen rising from the apex of the tail arc.

[68][69][70] In 1894, Irish fluid dynamicist Osborne Reynolds (1842–1912) studied the formation and collapse of vapor bubbles in boiling liquids and in constricted tubes.

[78] The mathematical models of cavitation which were developed by British engineer Stanley Smith Cook (1875–1952) and by Lord Rayleigh revealed that collapsing bubbles of vapor could generate very high pressures, which were capable of causing the damage that had been observed on ships' propellers.

[79][80] Experimental evidence of cavitation causing such high pressures was initially collected in 1952 by Mark Harrison (a fluid dynamicist and acoustician at the U.S. Navy's David Taylor Model Basin at Carderock, Maryland, USA) who used acoustic methods and in 1956 by Wernfried Güth (a physicist and acoustician of Göttigen University, Germany) who used optical Schlieren photography.

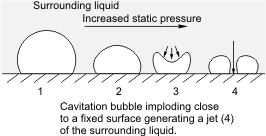

[81][82][83] In 1944, Soviet scientists Mark Iosifovich Kornfeld (1908–1993) and L. Suvorov of the Leningrad Physico-Technical Institute (now: the Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia) proposed that during cavitation, bubbles in the vicinity of a solid surface do not collapse symmetrically; instead, a dimple forms on the bubble at a point opposite the solid surface and this dimple evolves into a jet of liquid.

[85] Kornfeld and Suvorov's hypothesis was confirmed experimentally in 1961 by Charles F. Naudé and Albert T. Ellis, fluid dynamicists at the California Institute of Technology.

Minin at the Institute of Hydrodynamics (Novosibirsk, Russia) in 1957–1960, who examined also the first convenient model of a screen - a sequence of alternating flat one-dimensional liquid and gas layers.