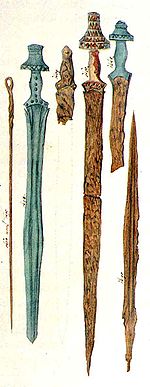

Iron Age sword

They were work-hardened, rather than quench-hardened, which made them about the same or only slightly better in terms of strength and hardness to earlier bronze swords.

It took a long time, however, before this was done consistently, and even until the end of the early medieval period, many swords were still unhardened iron.

The late Roman Empire introduced the longer spatha (the term for its wielder, spatharius, became a court rank in Constantinople).

With the spread of the La Tene culture at the 5th century BC, iron swords had completely replaced bronze all over Europe.

The most common is the "long" sword, which usually has a stylised anthropomorphic hilt made from organic material, such as wood, bone, or horn.

[4] Polybius (2.33) reports that the Gauls at the Battle of Telamon (224 BC) had inferior iron swords which bent at the first stroke and had to be straightened with the foot against the ground.

Plutarch, in his life of Marcus Furius Camillus, likewise reports on the inferiority of Gaulish iron, making the same claim that their swords bent easily.

These reports have puzzled some historians, since by that time the Celts had a centuries long tradition of iron workmanship.

[5] In 1906 a scholar suggested that the Greek observers misunderstood ritual acts of sword-bending, which may have served to "decommission" the weapon.

Quench hardening takes full advantage of the potential hardness of the steel, but leaves it brittle, and prone to breaking.

Tempering is heating the steel at a lower temperature after quenching to remove the brittleness while keeping most of the hardness.