Censorship in Italy

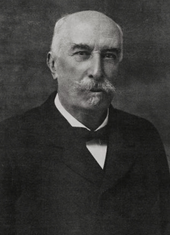

Many of the laws regulating freedom of the press in the modern Italian Republic come from the liberal reform promulgated by Giovanni Giolitti in 1912, which also established universal suffrage for all male citizens of the Kingdom of Italy.

In 1816, on the initiative of the Austrians, a literary monthly magazine entitled Biblioteca Italiana was founded in Milan, in which over 400 intellectuals and men of letters from all over Italy were invited to collaborate (not always successfully).

[4] The situation of Italian journalism began to change with the foundation of numerous clandestine newspapers, printed by Carbonari nuclei and underground revolutionary movements, which led to the uprisings of 1820–1821.

In fact, Antologia, a journal of science, literature and arts, founded in Florence in 1821, the Genoese Corriere Mercantile of 1824 and L'Indicatore genovese, to which the young Giuseppe Mazzini also collaborated, date back to those years.

Many of the laws regulating freedom of the press in the modern Italian Republic come from the liberal reform promulgated by Giovanni Giolitti in 1912, which also established universal suffrage for all male citizens of the Kingdom of Italy.

The subsequent regulation,[8] issued in 1914, listed a long series of prohibitions and transferred the power of intervention from the local public security authorities to the Ministry of the Interior.

[10] For the entire duration of the war, the authorities responsible for controlling the press, eager to present an optimistic picture of the situation to the public, suggested to the newspapers how to select the news.

With the decree of 29 June 1919, the restrictive regulations that came into force in the spring of 1915 were repealed; at the same time, the general director of public security, Vincenzo Quaranta, reduced surveillance on the media.

In literature, editorial industries had their own controlling servants steadily on site, but sometimes it could happen that some texts reached the libraries and in this case, an efficient organization was able to capture all the copies in a very short time.

Any work containing themes about Jewish culture, freemasonry, communist, or socialist ideas, was removed also by libraries (but it has been said that effectively the order was not executed with zeal, being a very unpopular position of the Regime).

Newer revisionists talk about the servility of journalists, but are surprisingly followed in this concept by many other authors and by some leftist ones too, since the same suspect was always attributed to the Italian press, before, during and after the Ventennio, and still in recent times the category has not completely demonstrated yet its independence from "strong powers".

The control of legitimate papers was practically operated by faithful civil servants at the printing machines and this allowed reporting a common joke affirming that any text that could reach readers had been "written by the Duce and approved by the foreman".

Fascist censorship promoted papers with wider attention to mere chronology of delicate political moments, to distract public opinion from dangerous passages of the government.

[17] In 1924–1925, during the most violent times of fascism (when squads used brutality against opposition) with reference to the death of Giacomo Matteotti killed by fascists, Marc'Aurelio published a series of heavy jokes and "comic" drawings describing dictator Benito Mussolini finally distributing peace.

The new Prime Minister, General Pietro Badoglio, instead of suppressing the Ministry of Popular Culture, suspended its activities and used it to transmit new orders aimed at controlling the press.

[31][32] Italy put an embargo on foreign bookmakers over the Internet (in violation of EU market rules) by mandating certain edits to DNS host files of Italian ISPs.

[34] Advertisements promoting Videocracy, a Swedish documentary examining the influence of television on Italian culture over the last 30 years, was refused airing purportedly because it says the spots are an offence to Premier Silvio Berlusconi.

[37] In 1950 a cartoon published in Candido (n. 25 of 18 June), drawn by Carletto Manzoni, cost Giovannino Guareschi, co-director of the weekly at the time, his first conviction for contempt of the President of Italy, Luigi Einaudi.

[40] In 1962, a new law on the review of films and theatrical works was approved,[41] which remained in force until 2021: although it brought about some changes, it confirmed the maintenance of a preventive system of censorship and made screening subject to the release of authorization.

Thus religion is the object of censorship, a particularly sensational case of Dio è morto ("God is dead") sung by Nomadi, which is censored by RAI but regularly broadcast by Vatican Radio.

Another sensitive topic is sex, the object of particularly ferocious censorship, as happens for example in the case of Je t'aime... moi non-plus, sung by Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin in 1969, a record which was seized and its sale permanently prohibited.

The program had tackled sensitive issues in the past that exposed the journalists to legal action (for example the authorization of buildings that did not meet earthquake-resistance specifications, cases of overwhelming bureaucracy, the slow process of justice, prostitution, health care scandals, bankrupt bankers secretly owning multimillion-dollar paintings, waste mismanagement involving dioxin toxic waste, cancers caused by asbestos anti-fire shielding (Eternit) and environmental pollution caused by a coal power station near the city of Taranto).

In 2004, it was demoted to "Partly Free", due to "20 years of failed political administration", the "controversial Gasparri's Law of 2003" and the "possibility for prime minister to influence the RAI (Italian state-owned Radio-Television), a conflict of interests among the most blatant in the World".

Freedom House noted that Italy constitutes "a regional outlier" and particularly quoted the "increased government attempts to interfere with editorial policy at state-run broadcast outlets, particularly regarding coverage of scandals surrounding prime minister Silvio Berlusconi.

In February 2004, the journalist Massimiliano Melilli was sentenced to 18 months in prison and a €100,000 fine for two articles, published on 9 and 16 November 1996, that reported rumours of "erotic parties" supposedly attended by members of Trieste high society.

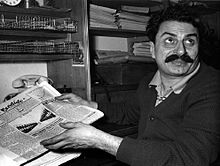

[51][52] In July, magistrates in Naples placed Lino Jannuzzi, a 76-year-old journalist and senator, under house arrest, although they allowed him the possibility of attending the work of the parliament during daytime.

In 2002, he was arrested, found guilty of "defamation through the press" ("diffamazione a mezzo stampa"), and sentenced to 29 months' imprisonment because of articles that appeared in a local paper for which he was editor-in-chief.

Reporters Without Borders states that in 2004, "The conflict of interests involving prime minister Silvio Berlusconi and his vast media empire was still not resolved and continued to threaten news diversity".

[58] Berlusconi's influence over RAI became evident when in Sofia, Bulgaria he expressed his views on journalists Enzo Biagi and Michele Santoro,[59] and comedian Daniele Luttazzi.

[65] In October 2009, Reporters Without Borders Secretary-General Jean-François Julliard declared that Berlusconi "is on the verge of being added to our list of Predators of Press Freedom", which would be a first for a European leader.