Cent (music)

Cents, as described by Alexander John Ellis, follow a tradition of measuring intervals by logarithms that began with Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz in the 17th century.

[a] Ellis chose to base his measures on the hundredth part of a semitone, 1200√2, at Robert Holford Macdowell Bosanquet's suggestion.

Making extensive measurements of musical instruments from around the world, Ellis used cents to report and compare the scales employed,[1] and further described and utilized the system in his 1875 edition of Hermann von Helmholtz's On the Sensations of Tone.

[2][3] Alexander John Ellis' paper On the Musical Scales of Various Nations,[1] published by the Journal of the Society of Arts in 1885, officially introduced the cent system to be used in exploring, by comparing and contrasting, musical scales of various nations.

"[4] Ellis defined the pitch of a musical note in his 1880 work History of Musical Pitch[5] to be "the number of double or complete vibrations, backwards and forwards, made in each second by a particle of air while the note is heard".

The result is called equal temperament or tuning, and is the system at present used throughout Europe.

"[10] Ellis presents applications of the cent system in this paper on musical scales of various nations, which include: (I. Heptatonic scales) Ancient Greece and Modern Europe,[11] Persia, Arabia, Syria and Scottish Highlands,[12] India,[13] Singapore,[14] Burmah[15] and Siam,;[16] (II.

Pentatonic scales) South Pacific, [17] Western Africa,[18] Java,[19] China[20] and Japan.

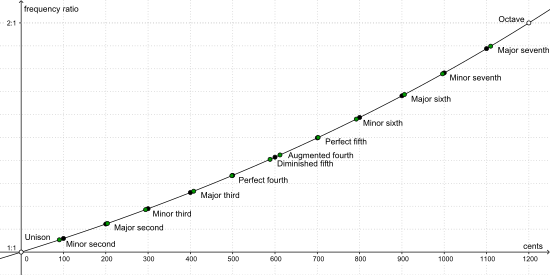

An equally tempered semitone (the interval between two adjacent piano keys) spans 100 cents by definition.

This error is well below anything humanly audible, making this piecewise linear approximation adequate for most practical purposes.

[23] The threshold of what is perceptible, technically known as the just noticeable difference (JND), also varies as a function of the frequency, the amplitude and the timbre.

In one study, changes in tone quality reduced student musicians' ability to recognize, as out-of-tune, pitches that deviated from their appropriate values by ±12 cents.

[24] It has also been established that increased tonal context enables listeners to judge pitch more accurately.

[25] "While intervals of less than a few cents are imperceptible to the human ear in a melodic context, in harmony very small changes can cause large changes in beats and roughness of chords.

[28] Normal adults are able to recognize pitch differences of as small as 25 cents very reliably.

[30] As early as 1647, Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz (1606-1682) in a letter to Athanasius Kircher described the usage of base-2 logarithms in music.

Joseph Sauveur, in his Principes d'acoustique et de musique of 1701, proposed the usage of base-10 logarithms, probably because tables were available.

The base-10 logarithm of 2 is equal to approximately 0.301, which Sauveur multiplies by 1000 to obtain 301 units in the octave.

[32] Félix Savart (1791-1841) took over Sauveur's system, without limiting the number of decimals of the logarithm of 2, so that the value of his unit varies according to sources.

[34][35] Early in the 19th century, Gaspard de Prony proposed a logarithmic unit of base

[36] Alexander John Ellis in 1880 describes a large number of pitch standards that he noted or calculated, indicating in pronys with two decimals, i.e. with a precision to the 1/100 of a semitone,[37] the interval that separated them from a theoretical pitch of 370 Hz, taken as point of reference.

) equal to two cents (22⁄1200)[39][40] proposed as a unit of measurement (Playⓘ) by Widogast Iring in Die reine Stimmung in der Musik (1898) as 600 steps per octave and later by Joseph Yasser in A Theory of Evolving Tonality (1932) as 100 steps per equal tempered whole tone.

At any particular instant, the two waveforms reinforce or cancel each other more or less, depending on their instantaneous phase relationship.

A piano tuner may verify tuning accuracy by timing the beats when two strings are sounded at once.