Central heating

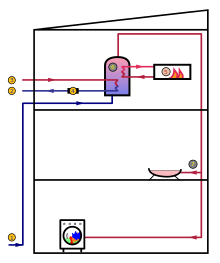

A central heating system may take up considerable space in a home or other building, and may require supply and return ductwork to be installed at the time of construction.

[1] Some other buildings utilize central solar heating, in which case the distribution system normally uses water circulation.

A Neolithic Age archaeological site, circa 5000 BC, discovered in Sonbong, Rason, in present-day North Korea, shows a clear vestige of gudeul in the excavated dwelling (Korean: 움집).

The main components of the traditional ondol are an agungi (firebox or stove) accessible from an adjoining room (typically kitchen or master bedroom), a raised masonry floor underlain by horizontal smoke passages, and a vertical, freestanding chimney on the opposite exterior wall providing a draft.

[3] The furnace burned mainly rice paddy straws, agricultural crop waste, biomass or any kind of dried firewood.

Unlike modern-day water heaters, the fuel was either sporadically or regularly burned (two to five times a day), depending on frequency of cooking and seasonal weather conditions.

[5][6] The Roman hypocaust continued to be used on a smaller scale during late Antiquity and by the Umayyad caliphate, while later Muslim builders employed a simpler system of underfloor pipes.

In Reichenau Abbey a network of interconnected underfloor channels heated the 300 m2 large assembly room of the monks during the winter months.

[8] In the 13th century, the Cistercian monks revived central heating in Christian Europe using river diversions combined with indoor wood-fired furnaces.

The well-preserved Royal Monastery of Our Lady of the Wheel (founded 1202) on the Ebro River in the Aragon region of Spain provides an excellent example of such an application.

[9] William Strutt designed a new mill building in Derby with a central hot air furnace in 1793, although the idea had been already proposed by John Evelyn almost a hundred years earlier.

He published his ideas in The Philosophy of Domestic Economy; as exemplified in the mode of Warming, Ventilating, Washing, Drying, & Cooking, ... in the Derbyshire General Infirmary in 1819.

Sylvester documented the new ways of heating hospitals that were included in the design, and the healthier features such as self-cleaning and air-refreshing toilets.

They were widely copied in the new mills of the Midlands and were constantly improved, reaching maturity with the work of de Chabannes on the ventilation of the House of Commons in the 1810s.

The English writer Hugh Plat proposed a steam-based central heating system for a greenhouse in 1594, although this was an isolated occurrence and was not followed up until the 18th century.

[12] A central boiler supplied high-pressure steam that then distributed the heat within the building through a system of pipes embedded in the columns.

[13] Another early hot water system was developed in Russia for central heating of the Summer Palace (1710–1714) of Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg.

Jean Simon Bonnemain (1743–1830), a French architect,[14] introduced the technique to industry on a cooperative, at Château du Pêcq, near Paris.

One of the first modern hot water central heating systems to remedy this deficiency was installed by Angier March Perkins in London in the 1830s.

At that time central heating was coming into fashion in Britain, with steam or hot air systems generally being used.

Franz San Galli, a Prussian-born Russian businessman living in St. Petersburg, invented the radiator between 1855 and 1857, which was a major step in the final shaping of modern central heating.

Some central heating plants can switch fuels for reasons of economy and convenience; for example, a home owner may install a wood-fired furnace with electrical backup for occasional unattended operation.

Solid fuels such as wood, peat or coal can be stockpiled at the point of use, but are inconvenient to handle and difficult to automatically control.

The distribution network is more costly to build than for gas or electric heating, and so is only found in densely populated areas or compact communities.

Tall buildings take advantage of the low density of steam to avoid the excessive pressure required to circulate hot water from a basement-mounted boiler.

[24] Public and commercial properties are directly and indirectly responsible for 30% of the final energy consumed around the world, including almost 55% of global electricity consumption.

[25] Heating is currently responsible for around 45% of building emissions, and still relying on fossil fuels for supplying more than 55% of its final energy consumption.

In such buildings which require isolated heating, one may wish to consider non-central systems such as individual room heaters, fireplaces or other devices.

Alternatively, architects can design new buildings which can virtually eliminate the need for heating, such as those built to the Passive House standard.

This offers the option of relatively easy conversion in the future to use developing technologies such as heat pumps and solar combisystems, thereby also providing future-proofing.