Cesare Borgia

He was born in Subiaco in Lazio, Italy[1][2] in either 1475 or 1476, the illegitimate son of Cardinal Roderic Llançol i de Borja, usually known as "Rodrigo Borgia", later Pope Alexander VI, and his Italian mistress Vannozza dei Cattanei, about whom information is sparse.

The Italian historian Stefano Infessura writes that Cardinal Borgia falsely claimed Cesare to be the legitimate son of another man—Domenico d'Arignano, the nominal husband of Vannozza dei Cattanei.

[4] Alexander VI staked the hopes of the Borgia family on Cesare's brother Giovanni, who was made captain-general of the military forces of the papacy.

Cesare's career was founded upon his father's ability to distribute patronage, along with his alliance with France (reinforced by his marriage with Charlotte d'Albret, sister of John III of Navarre), in the course of the Italian Wars.

Louis XII invaded Italy in 1499; after Gian Giacomo Trivulzio had ousted its duke Ludovico Sforza, Cesare accompanied the king in his entrance into Milan.

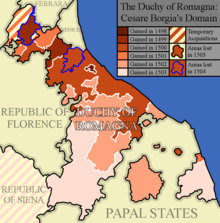

[citation needed] At this point, Alexander decided to profit from the favourable situation and carve out for Cesare a state of his own in northern Italy.

[citation needed] Cesare was appointed commander of the papal armies with a number of Italian mercenaries, supported by 300 cavalry and 4,000 Swiss infantry sent by the king of France.

Alexander sent him to capture Imola and Forlì, ruled by Caterina Sforza (mother of the Medici condottiero Giovanni dalle Bande Nere).

Despite being deprived of his French troops after the conquest of those two cities, Borgia returned to Rome to celebrate a triumph and to receive the title of Papal Gonfalonier from his father.

However, his condottieri, most notably Vitellozzo Vitelli and the Orsini brothers (Giulio, Paolo and Francesco), feared Cesare's cruelty and set up a plot against him.

[15] Cesare Borgia, who was facing the hostility of Ferdinand II of Aragon,[17] was betrayed[citation needed] while in Naples by Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, a man he had considered his ally, and imprisoned there, while his lands were retaken by the papacy.

[17] He did manage to escape from the Castle of La Mota with assistance, and after running across Santander, Durango and Gipuzkoa, he arrived in Pamplona on 3 December 1506, and was much welcomed by King John III of Navarre,[18] who was missing an experienced military commander, ahead of the feared Castilian invasion.

He was then stripped of all his luxurious garments, valuables, and a leather mask covering half his face (disfigured, possibly by syphilis, during his late years).

[18] Borgia was originally buried in a marbled mausoleum King John III had ordered built at the altar of the Church of Santa María in Viana in Navarre in northern Spain, set on one of the stops on the Camino de Santiago.

In the 16th century the Bishop of Mondoñedo, Antonio de Guevara, published from memory what he had seen written on the tomb when he had paid a visit to the church.

This epitaph underwent several changes in wording and meter throughout the years and the version most commonly cited today is that published by the priest and historian Francisco de Alesón in the 18th century.

[citation needed] Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, in A los pies de Venus, writes that the then Bishop of Santa María had Borgia expelled from the church because his own father had died after being imprisoned under Alexander VI.

It was held for many years that the bones were lost, although in fact local tradition continued to mark their place quite accurately and folklore sprung up around Borgia's death and ghost.

A movement was made in the late 1980s to have Borgia dug up once more and put back into Santa María, but this proposal was ultimately rejected by church officials due to a recent ruling against the interment of anyone who did not hold the title of pope or cardinal.

[24] Others, including Macaulay and Lord Acton, have historicized Machiavelli's Borgia, explaining the admiration for such violence as an effect of the general criminality and corruption of the time.

The arrangement was part of a plan by the Navarrese monarchs to ease tensions with the newly proclaimed French King Louis XII by offering a royal blood bride in his dealings with the Holy See.

He alternated bursts of demonic activity when he stayed up all night receiving and dispatching messengers, with moments of unaccountable sloth when he remained in bed refusing to see anyone.

He was quick to take offence and rather remote from his immediate entourage, yet he was very open with his subjects, loving to join local sports and cutting a dashing figure.

However, at other times, Machiavelli observed Cesare as having "inexhaustible" energy and an unrelenting genius in military matters, and also diplomatic affairs, and he would go days and nights on end without seemingly requiring sleep.