Challah

Challah or hallah (/ˈxɑːlə, ˈhɑːlə/ (K)HAH-lə;[1] Hebrew: חַלָּה, romanized: ḥallā, pronounced [χaˈla, ħalˈlaː]; pl.

[2] Similar (usually braided) breads with mainly the same ingredients include brioche, kalach, kozunak, panettone, pulla, tsoureki, vánočka found across European cuisines.

According to Ludwig Köhler [de], challah was a sort of bread with a central hole, designed to hang over a post.

Author of A Blessing of Bread, Maggie Glezer, writes that the braiding began in 15th century Austria and Southern Germany, "with Jewish housewives following their non-Jewish counterparts, who plaited the loaves they baked on Sundays".

Another food historian Hélène Jawhara Piñer, a scholar of medieval Sephardic cuisine, has suggested that a recipe for a leavened and braided bread found in a 13th century Arabic cookbook from Spain, the Kitāb al-ṭabīẖ, may have been a precursor to challah.

[12] According to Piñer's analysis, following their expulsion from Spain, Sephardic Jews brought this bread northward through Italy in the 15th and 16th centuries.

[15][16] Yiddish communities in different regions of Europe called the bread khale, berkhes or barches, bukhte, dacher, kitke, koylatch or koilitsh, or shtritsl.

[18] The term koylatch is cognate with the names of similar braided breads which are consumed on special occasions by other cultures outside the Jewish tradition in a number of European cuisines.

These are the Russian kalach, the Serbian kolač, the Ukrainian kolach the Hungarian kalács (in Hungary, the Jewish variant is differentiated as Bárhesz), and the Romanian colac.

These names originated from Proto-Slavic kolo meaning "circle", or "wheel", and refer to the circular form of the loaf.

[citation needed] Most traditional Ashkenazi challah recipes use numerous eggs, fine white flour, water, sugar, yeast, oil (such as vegetable or canola), and salt, but "water challah" made without eggs and having a texture like French baguette also exists, which is typically suitable for those following vegan diets.

Challah is almost always pareve (containing neither dairy nor meat—important in the laws of Kashrut), unlike brioche and other enriched European breads, which contain butter or milk as it is typically eaten with a meat meal.

Israeli breads for shabbat are very diverse, reflecting the traditions of Persian, Iraqi, Moroccan, Russian, Polish, Yemeni, and other Jewish communities who live in the State of Israel.

[22] This "double loaf" (in Hebrew: לחם משנה) commemorates the manna that fell from the heavens when the Israelites wandered in the desert after the Exodus.

[citation needed] Challot - in these cases extremely large ones - are also sometimes eaten at other occasions, such as a wedding or a Brit milah, but without ritual.

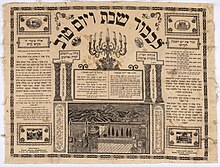

[citation needed] It is customary to begin the evening and day Sabbath and holiday meals with the following sequence of rituals: The specific practice varies.

The Romanian colac is a similar braided bread traditionally presented for holidays and celebrations such as Christmas caroling colindat.

A sweet bread called milibrod (Macedonian: милиброд), similarly braided as the challah, is part of the dinner table during Orthodox Easter in Macedonia.