Charge qubit

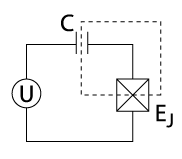

The quantum superposition of charge states can be achieved by tuning the gate voltage U that controls the chemical potential of the island.

The charge qubit is typically read-out by electrostatically coupling the island to an extremely sensitive electrometer such as the radio-frequency single-electron transistor.

[5] Recent work has shown T2 times approaching 100 μs using a type of charge qubit known as a transmon inside a three-dimensional superconducting cavity.

[6][7] Understanding the limits of T2 is an active area of research in the field of superconducting quantum computing.

The devices are usually made on silicon or sapphire wafers using electron beam lithography (different from phase qubit, which uses photolithography) and metallic thin film evaporation processes.

Note that some recent papers[8][9] adopt a different notation, and define the charging energy as that of one electron: and then the corresponding Hamiltonian is: To-date, the realizations of qubits that have had the most success are ion traps and NMR, with Shor's algorithm even being implemented using NMR.

[10] However, it is hard to see these two methods being scaled to the hundreds, thousands, or millions of qubits necessary to create a quantum computer.

Superconductors, however, have the advantage of being more easily scaled, and they are more coherent than normal solid-state systems.

Design was theoretically described in 1997 by Shnirman,[11] while the evidence of quantum coherence of the charge in a Cooper pair box was published in February 1997 by Vincent Bouchiat et al.[12] In 1999, coherent oscillations in the charge Qubit were first observed by Nakamura et al.[13] Manipulation of the quantum states and full realization of the charge qubit was observed 2 years later.

[14] In 2007, a more advanced device known as Transmon showing enhanced coherence times due to its reduced sensitivity to charge noise was developed at Yale University by Robert J. Schoelkopf, Michel Devoret, Steven M. Girvin and their colleagues .