Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway

When opened in 1907, the CCE&HR's line served 16 stations and ran for 7.67 miles (12.34 km)[1] in a pair of tunnels between its southern terminus at Charing Cross and its two northern termini at Archway and Golders Green.

Within the first year of opening, it became apparent to the management and investors that the estimated passenger numbers for the CCE&HR and the other UERL lines had been over-optimistic.

In November 1891, notice was given of a private bill that would be presented to Parliament for the construction of the Hampstead, St Pancras & Charing Cross Railway (HStP&CCR).

[note 2] Bills for three similarly inspired new underground railways were also submitted to Parliament for the 1892 legislative session, and, to ensure a consistent approach, a Joint Select Committee was established to review the proposals.

The committee took evidence on various matters regarding the construction and operation of deep-tube railways, and made recommendations on the diameter of tube tunnels, method of traction, and the granting of wayleaves.

After preventing the construction of the branch beyond Euston, the Committee allowed the HStP&CCR bill to proceed for normal parliamentary consideration.

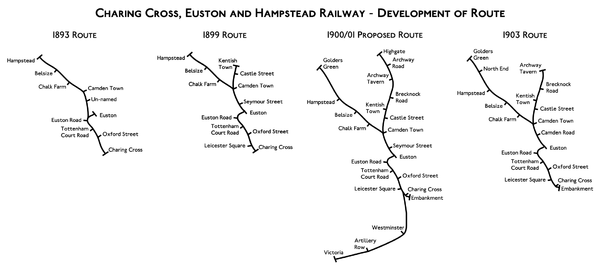

The rest of the route was approved and, following a change of the company name, the bill received royal assent on 24 August 1893 as the Charing Cross, Euston, and Hampstead Railway Act 1893 (56 & 57 Vict.

[note 3] Only the W&CR, which was the shortest line and was backed by the London and South Western Railway with a guaranteed dividend, was able to raise its funds without difficulty.

[note 4] To keep the powers granted by the act alive, the CCE&HR submitted a series of further bills to Parliament for extensions of time.

[13] In 1900, foreign investors came to the rescue of the CCE&HR: American financier Charles Yerkes, who had been lucratively involved in the development of Chicago's tramway system in the 1880s and 1890s, saw the opportunity to make similar investments in London.

[note 5] With the CCE&HR and the other companies under his control, Yerkes established the UERL to raise funds to build the tube railways and to electrify the steam-operated MDR.

On 24 November 1894, a bill was announced to purchase additional land for stations at Charing Cross, Oxford Street, Euston and Camden Town.

[18] On 23 November 1897, a bill was announced to change the route of the line at its southern end to terminate under Craven Street on the south side of Strand.

While this provided a convenient site for the CCE&HR's depot[note 8] it is believed that underlying the decision was Yerkes' plan to profit from the sale of development land previously purchased in the area that would rise in value when the railway opened.

The Hampstead Heath Protection Society claimed that the tunnels would drain the sub-soil of water and the vibration of passing trains would damage trees.

Moreover, it seems to be established beyond question that the trains passing along these deep-laid tubes shake the earth to its surface, and the constant jar and quiver will probably have a serious effect upon the trees by loosening their roots.

[note 13] Once Parliament was satisfied that the extension would not damage the Heath, the CCE&HR bills jointly received royal assent on 18 November 1902 as the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act 1902 (2 Edw.

[44] This consisted of two-storey steel-framed buildings faced with red glazed terracotta blocks with wide semi-circular windows on the upper floor.

[note 17] The sale of the building land at North End to conservationists to form the Hampstead Heath extension in 1904, meant a reduction in the number of residents who might use the station there.

[54] The official opening on 22 June 1907 was made by David Lloyd George, President of the Board of Trade, after which the public travelled free for the rest of the day.

[45] These carriages were built to the same design used for the BS&WR and the GNP&BR and operated as electric multiple unit trains without the need for separate locomotives.

[61] In an effort to improve the financial situation, the UERL together with the C&SLR, the CLR and the GN&CR began, from 1907, to introduce fare agreements.

[63] In November 1910, the LER published notice of a bill to revive the unused 1902 permission to continue the line from Charing Cross to Embankment.

5. c. lxxxv)[72] granted extensions of time, approved changes to the route, gave permissions for viaducts and a tunnel and allowed the closure and re-routeing of roads to be crossed by the railway's tracks.

The UERL group's Managing Director/Chairman, Lord Ashfield, ceremonially cut the first sod to begin the works at Golders Green on 12 June 1922.

[78] The work involved the rebuilding of the below ground parts of the CCE&HR's former terminus station to enable through running and the loop tunnel was abandoned.

Tunnels were extended under the Thames to Waterloo station and then to Kennington where two additional platforms were constructed to provide the interchange to the C&SLR.

With the opening of the Kennington extension, the two railways began to operate as an integrated service using the newly built Standard Stock trains.

In an effort to protect the UERL group's income Lord Ashfield lobbied the government for regulation of transport services in the London area.

Ashfield aimed for regulation that would give the UERL group protection from competition and allow it to take substantive control of the LCC's tram system; Morrison preferred full public ownership.